Q&A with the Scholars: Down Syndrome and Prenatal Testing

Mark Bradford is President of the Jerome Lejeune Foundation USA since 2012. Mr. Bradford has been researching Down syndrome-related issues and advocating for individuals with Down syndrome since his son, Thomas, was born with Down syndrome in 2001. He has been a featured expert contributor for CLI’s website, and his major CLI paper can be found here: “Improving Joyful Lives: Society’s Response to Difference and Disability.” In this interview, he discusses Down syndrome and prenatal testing.

What is Down syndrome? How common is it for a child to be conceived with Down syndrome?

Bradford: Down syndrome, otherwise known as trisomy 21, is a genetic condition in which an individual usually has an extra copy of the 21st chromosome in every cell of their body. There are more rare forms of Down syndrome where the extra chromosome only appears in some cells of the body but not all, or where a piece of chromosome 21 breaks off and attaches to another of the chromosomes. According to the newest research by Dr. Brian Skotko and his colleagues, the estimated live birth prevalence for Down syndrome in the United States is approximately 12.6 per 10,000, or a total of around 5,300 births each year. So, about one in every 792 births is a child with Down syndrome.[1]

Many people seem to view the prospect of raising a child with Down syndrome with fear. How can we most effectively communicate an accurate message about the lives led by people with Down syndrome and their families—who often relate the blessings and happiness that they have gained through their experience?

Bradford: Advocates struggle to answer this question every day. There are two issues: people fear the unknown; and, every parent wants to have a “perfect” child. Those of us in the U.S., and in many other countries, have been enculturated to fear and reject genetic differences like Down syndrome. We can’t forget that the U.S. has a long history—promoted by the progressive movement, the same movement that brought us Roe v Wade and that is promoting prenatal screening—of rejecting those who are different. Adam Cohen documented the history of genetic discrimination and the eugenic movement in the U.S. in a book published last year called Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck.

Disability is a fearful unknown to most people. Many are unable, or unwilling, to accept that any child that comes to them is perfect, and that what is actually imperfect is our love and our understanding that all children are a gift, and that all human life is beautiful—period. We can see with horrific clarity in the ongoing movement to legalize physician-assisted suicide that the connection between suffering and love has been severed. Because of its historical treatment, parents associate Down syndrome—most often incorrectly—with suffering, and that is an association still promoted by many in the medical professions. In the context of a society that embraces legal abortion, even the well-intentioned see abortion as an acceptable means to “save” their child from a suffering that they have been led to believe Down syndrome brings.

How can we communicate the reality of Down syndrome more effectively? In several states, laws have been passed that require accurate, current, and balanced information be provided to families that receive a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome to try to help overcome the stigma long associated with disability. That’s a good start. Mark Leach has done an excellent job of advocating for these laws and documenting their progress on his blog, http://www.downsyndromeprenataltesting.com/.

Also, those with Down syndrome are now more commonly seen in schools alongside their peers. Every fall there seem to be more and more news stories about students with Down syndrome being elected as a homecoming queen or king in public high schools. We need to keep moving in this direction, but we also need to provide peer supports to families that receive a prenatal diagnosis to help encourage them past their initial fear and perhaps their first instinct to abort. Of course, support can’t end with a decision to give birth to a child. We still have a lot of work to do in providing good educational and work opportunities to individuals with Down syndrome as they age.

I believe that the decision to abort is responsible for far more sadness and family difficulties than the acceptance of a child with Down syndrome who truly does bring a family’s capacity for love to a whole new level.

How does prenatal testing for Down syndrome work, and when during pregnancy are the tests done? How has prenatal testing technology developed over time, and in what countries is it available?

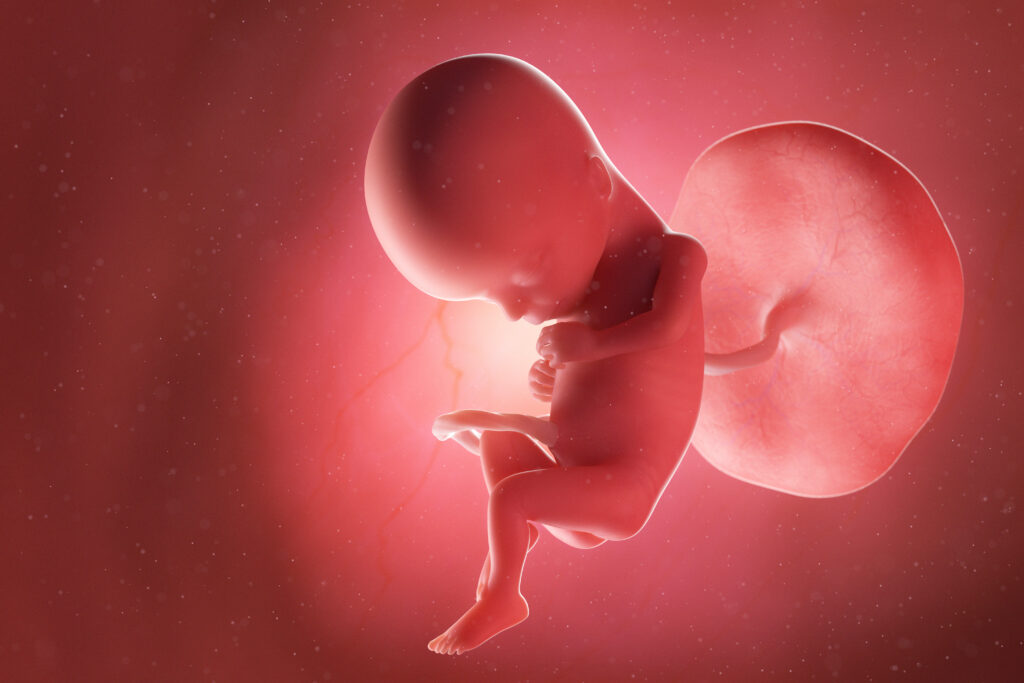

Bradford: In the past there have been two categories of prenatal tests: invasive diagnostic tests like amniocentesis that can actually examine the DNA of a child and look for genetic anomalies; and noninvasive screening tests like blood tests that look for serum markers in maternal blood that indicate a possibility of Down syndrome. Sonograms that can see structural markers for Down syndrome in the developing fetus also fall into this category.

Invasive tests have always been the most accurate, but they carry a slight risk of miscarriage. Since 2011 so called “non-invasive prenatal screening” has become available in the U.S. and is now spreading to other parts of the world. These tests, more accurately called “cell-free DNA tests,” can identify fragments of DNA from the fetus that are shed from the placenta and make their way into the mother’s blood. Even more alarming, the technology now exists—but is not yet commercially available—to isolate nucleated red blood cells from the fetus in maternal blood. Whereas cell-free DNA testing is very accurate but cannot be considered truly diagnostic because of the potential for error, nucleated cells will provide for direct analysis of the fetal genome. In other words, it will be a noninvasive way of providing prenatal testing as accurately as amniocentesis but without the risk of miscarriage.

Cell-free DNA screening is spreading rapidly throughout the world. Recent market reports show that the anticipated growth of this technology worldwide is tremendous. According to these reports, investors in this technology can anticipate a compounded annual growth rate of 17.5% until 2022. That is an increase in value from $0.5 billion in 2013 to $2.3 billion in 2022. My recent article for the Charlotte Lozier Institute details a documentary that was made by the actress Sally Phillips last year called “A World Without Down Syndrome?” Ms. Phillips presents the push for cell-free DNA testing in the U.K. and beautifully challenges the assumptions that are driving the effort. Of course, the tests have been approved now and will be provided by their National Health Service in short order to all pregnant women.

How prevalent is disability-discrimination abortion following a diagnosis of Down syndrome in the United States? In other countries? Have laws prohibiting abortion based on disability met with any success so far?

Bradford: I referenced above research that was done by Dr. Brian Skotko and his colleagues in the context of birth prevalence, but this research was actually done to document a response to this very question. To summarize, Skotko et al. estimated that there are approximately 3,100 abortions following a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome each year in the U.S. Taking natural losses into account (natural miscarriage), the number of Down syndrome births in the absence of abortion should have been 7,600. They conclude that prenatal diagnosis and abortion since 1974 have reduced the population living with Down syndrome by 30%. Advocates in Europe report that the termination rate following prenatal diagnosis is above 90%, and some claim in some areas that number is at least 96%. Sally Phillips in her documentary visits with a doctor in Iceland who agrees that the termination rate there is 100%! I suppose that should console us somewhat in the U.S. that our termination rate is not that extreme, but of course, even a one percent voluntary termination rate would be too high.

States in the U.S. are beginning to pass laws to prohibit disability selective abortion, but those laws are being challenged. With Donald Trump’s promise to appoint justices to the Supreme Court that are pro-life, or at least originalists, perhaps these laws will stand and even spread to other states, especially if Roe v Wade is overturned. It cannot be denied that even the court that decided Roe realized that the states should be entitled to make provision for the protection of innocent human life. I think we have some interesting times ahead of us.

Why are you pro-life? If you had 60 seconds to explain to someone why you have pursued the work that you have throughout your career, what do you tell them?

Bradford: Jerome Lejeune, a devout Catholic, said that if the Roman Catholic Church decided at some point in the future that abortion was permissible, he would no longer be a Roman Catholic. He didn’t need his religious faith to know that abortion is wrong. He knew that from his profession as a doctor, and even more fundamentally – because of his humanity. While we can certainly claim religious faith as a reason for being pro-life, I don’t think that is the best argument in a society where religious belief is seen as purely subjective and with little to offer in the public square. For me, your question has an easy response: Who am I to decide who lives and who dies? Anyone who claims to have that “right” should be feared. They are dangerous.

Before abortion was legal, there was no real disagreement over when human life begins, or any question that a fetus developing in the womb of a woman is truly a human being, albeit a tiny one. Sexual “mistakes,” disability, race, age, sex, or any other cause cannot be an excuse to interrupt the natural progression of a human life from its conception until natural death. We don’t have to imagine the consequences of admitting that kind of violence against human life into our culture. We can see the result all around us and it is devastating. I think the desire to pursue truth and defend human life, especially the most endangered, is worth the investment of one’s life.

[1] Gert de Graaf, Frank F. Buckley, Brian G. Skotko. (2015), Estimates of the live births, natural losses, and elective terminations with down syndrome in the United States. Am J Med Genet Part A 167A:756–767.