Pro-Life and Safety Net Health Services Initiatives under the Children’s Health Insurance Program

By Maya Noronha, J.D.

This is Issue 38 of the American Reports Series.

Executive Summary

- In the United States, states are permitted to use a portion of their Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) administrative funding to implement Health Services Initiatives (HSIs) for children’s health, but many states do not take advantage of this option.

- HSIs must serve children under 19 years old, potentially allowing for health funding that would serve unborn children and expectant teenage parents if other criteria, like poverty level, are met.

- To be reimbursed for CHIP funding by the federal government, states must identify how much funding is available and submit a State Plan Amendment for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to review.

- HSIs are an option for federal funding that offer many advantages, such as a high federal matching rate, a large amount of funds, a relatively simple procedure to access the funds, and a great deal of flexibility to design a program that best serves those in need.

- States should consider initiatives supporting pregnant women and their children both during pregnancy and postpartum. HSIs have been used for programs such as case management, newborn home visiting, prenatal care, health insurance, parenting education, and specialized training for medical personnel to strengthen their pro-life safety nets for women and families in need.

I. Introduction

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services permits states to use a limited amount of Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding to implement health services initiatives (HSIs) to improve the health of children. However, many states do not take advantage of this funding. According to the most recent available data from CMS, only 31 states implemented HSIs in fiscal year 2022.[1] Moreover, states that have opted to use HSIs have not always spent all available funding.[2] An HSI is a highly flexible opportunity to fund measures that help unborn children, adolescent pregnant or postpartum mothers, and young parents.

II. What are Health Services Initiatives?

Since the creation of CHIP in 1997, Congress has allowed states to use federal funds for “health services initiatives.”[3] Under the applicable provisions of the Social Security Act added in 1997, Congress allows funding for “health services initiatives … for improving the health of children (including targeted low-income children and other low-income children).”[4] CMS regulations define HSIs as activities that: (1) protect the public health; (2) protect the health of individuals; (3) improve or promote a state’s capacity to deliver public health services; or (4) strengthen the human and material resources necessary to accomplish public health goals relating to improving the health of children.[5]

In a “Frequently Asked Questions” (FAQ) guidance document issued in 2017,[6] CMS provided more details about HSIs, including the types of services funded and the age and poverty level of eligible beneficiaries. Beneficiaries of HSIs must be “less than 19 years of age.”[7] CMS also defines “low-income” as household income that is at or below 200% of the federal poverty level for the size of the family involved, which is a standard used for the eligibility of a child to enroll in CHIP and/or Medicaid.[8]

III. How Can States Implement HSIs?

There are three major steps for states to access federal funding for HSIs. First, the state must determine if it has available funds under CHIP. Second, the state must prepare an HSI application in the form of a State Plan Amendment (SPA) to CHIP and send this to CMS. Third, CMS must review the SPA and approve the application. Then, the state must report yearly to CMS through the CHIP Annual Report Template System, with an accounting of expenses for the HSI in order to receive federal reimbursement. Below, each of these steps is explained in more detail, and why these steps are preferable over procedures used to access other federal funds.

A. Funding Availability

If a state has not used up all its CHIP funding designated for administrative costs, it may use any remaining amount for HSIs. The amount available for CHIP administrative costs is capped at 10% of the state’s total CHIP expenditures.[9] Administrative expenses associated with ensuring regulatory requirements must be met and programmatic needs must be covered prior to funding an HSI.[10] CHIP administrative costs often include “stakeholder engagement, eligibility determinations and renewals, negotiation of contracts, performance measurement, and quality assurance activities.”[11]

B. State Plan Amendment

States must submit a CHIP State Plan Amendment (SPA) to CMS in order to implement an HSI. The state must prepare an SPA with a detailed description of the HSI program, including the HSI’s beneficiaries, purpose, need, limited time frame, planned budget, and effectiveness to ensure its quality and eligibility as an HSI.[12]

C. CMS Review and Approval

In reviewing an HSI proposal, CMS evaluates the amount of funds available under the 10% cap on HSI and administrative expenditures for CHIP to determine whether sufficient funds are available to cover the costs of the HSI in addition to necessary administrative expenses. The review process is a collaborative back and forth between the state and CMS. The time CMS takes to complete the review varies. For example, in 2021, New York had originally submitted two HSIs in a single SPA but CMS split the submission, approving the early intervention services HSI but still taking time to review the newborn screening HSI.[13] However, even if CMS takes a long time, the effective date of reimbursements has in some cases been applied retroactively to reimburse funds spent before the date the state applied or before the date CMS approved.[14]

D. Annual State Reporting

Every year, the state must report if and how much money from administrative costs were used to fund HSIs in their CHIP Annual Report Template System (CARTS).[15]

IV. Advantages of Using HSIs

There are financial advantages and the benefit of flexibility for states that elect to use HSIs, including a large amount of available funds. HSIs offer states a higher matching rate—using the enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (e-FMAP) formula for CHIP—than Medicaid.[16]

As compared to other funding mechanisms, HSIs offer fewer restrictions on states and less onerous procedures. To establish an HSI, a state does not need to seek a waiver,[17] provide public notice prior to submitting a CHIP HSI SPA,[18] or have a CHIP program that is separate from Medicaid.[19] States can also retroactively access federal funds; CMS has approved matching funds after submission date and for a prior fiscal year.[20] States can also adapt to changed circumstances after initial reporting; after the initial SPA, for example, a state may modify a prior year’s HSI with permissible changes by submitting a revised SPA.[21] In subsequent state amendments, states have modified previously approved HSIs to expand[22] or phase them out.[23]

While income, age, and child-specialized initiatives are baseline requirements, an HSI can be designed to serve a broader population—including different income levels, different ages, and serving the adults caring for a child. An initiative, for example, may set a maximum income level for families above the 200% federal poverty line and still be fully funded.[24] An initiative may also serve people ages 19 and above, but the federal government will only financially support the portion serving children under age 19.[25] Additionally, the HSI does not have to limit the initiative to children enrolled in Medicaid and/or CHIP.[26]

Furthermore, in addition to targeted direct services funding, a program can have a broader scope to serve public health.[27] The state, moreover, does not have to run its program solely at the state level or be state-wide; it can coordinate with local efforts[28] or limit it to specific areas within the state.[29] Furthermore, a state has the flexibility regarding how many HSIs to have, as CMS can approve more than one HSI per year for a state to run concurrently, if it has sufficient funds available.[30]

Given that the funding comes through the CHIP program, CMS recommends that states use an HSI, to the extent available, to enroll eligible children in the Medicaid or CHIP programs,[31] but past HSIs have addressed issues other than enrollment or health insurance.

HSIs, by statute, must address “health.” However, under the Biden administration, CMS approved programs that could be considered solely human or housing services as opposed to health care, such as homelessness programs without a clear nexus.[32] In 2024, the Biden administration took the policy position that HSIs may be used to serve health-related social needs (HRSN) and be based on social determinants of health (SDOH).[33] HHS’s Healthy People 2030 framework defined SDOH to include access to nutritious foods and physical activity opportunities; safe housing, transportation, and neighborhoods; education, job opportunities, and income.[34] Because the Biden administration included the social determinants of health policy in a preamble to a regulation, the Trump administration is not legally required to continue the previous administration’s policy approach. In 2025, the Trump administration rescinded the Biden administration guidance on the HSRN framework,[35] indicating that the Trump administration interprets “health services” less broadly than the Biden administration.[36]

The advantages of HSI use can extend beyond the immediate beneficiaries of the programs themselves. Another benefit of using life-affirming HSIs is that states report metrics and outcomes of programs to the federal government. These requirements can help the pro-life movement get better data about populations in need and identify effective program designs that can be used by different states as HSIs or serve as models for the design of future pro-life grant programs.

Finally, states should be aware that failing to use available funds over a two-year period results in reduced funding in future years, as those funds will be reallocated among other states.[37] Utilizing HSI opportunities as soon as possible will enable states to access federal matching funds for continued support of pregnant and parenting women and their children in years to come.

V. Designing New Pro-Life and Safety Net HSIs

States may look to trends in how previous approved programs were designed in order to help design their own HSIs geared towards life-affirming support and safety nets for women and children. In its 2017 guidelines, CMS describes its approved programs as typically involving “preventive services and interventions.”[38] Further, many states have used HSI funding to supplement existing state programs instead of starting new programs from scratch. For example, over the history of HSIs, their most common use has been for poison control centers and related initiatives that serve children.[39] Often, states have adopted programs substantially similar to programs in other states, such as the “Reach Out and Read” (ROR) program that has been implemented in Alabama, North Carolina, and Oklahoma.[40] States also often opt to tailor other states’ previously approved CMS programs to their own state programs, because there is precedent for past CMS approval, and the state can point to past evidence of effectiveness.[41] Finally, the other states’ submissions can be used as a template for filling out a state plan submission. Therefore, states may opt to use another state’s already approved life-affirming HSI program, as outlined below, and tailor it to their state.

Although the federal government offers the option to fund HSIs to all 50 states and D.C., as of February 2023, only 31 states had HSIs.[42] States that already have one or more HSIs that serve pregnant and parenting women or young parents in need can also benefit from adding new HSIs or expanding existing HSIs to strengthen the pro-life safety net.

HSIs offer program design flexibility. A state does not need to operate the HSI initiative statewide.[43] For example, states like Arkansas and Alabama have limited HSIs to individual counties in their states.[44] The California Rural Health Demonstration Project focused on rural areas.[45] States are also not restricted to initial program design and can transition the program’s services by submitting a new SPA. One example is Alabama’s ALL Babies HSI, which issued a state plan amendment to expand its initiative to 33 additional counties.[46]

A. Pro-Life and Safety Net HSIs

Previous HSI programs have specialized in serving populations including the unborn as well as pregnant, postpartum, and parenting women and their families. Services in these areas have included prenatal diagnosis and treatment, perinatal hospice, unplanned pregnancy hotlines, health insurance, breast feeding, and health support offered by case managers with home visits or in schools.

- Serving the Unborn as well as Pregnant, Postpartum, and Parenting Females

Notably, CMS has approved HSIs that states have reported as serving the “unborn,” including in Alabama,[47] California,[48] Virginia,[49] and Rhode Island.[50] CMS approved Wisconsin’s Asthma-Safe Homes Program serving “pregnant adults.”[51] Alabama’s HSI was open to “prenatally enrolled” children, allowing a mother to plan before birth by signing up her unborn child.[52] Furthermore, CHIP offers services to “targeted low-income children from-conception-to-end-of-pregnancy” (emphasis mine), for which the health services initiative could supplement funding beyond the scope of the program.[53]

- Case Management

Alabama’s Reducing Infant Mortality (RIM) program, created in 2019, provided “prenatal monitoring, case management and care coordination services to low-income, high-risk pregnant women and their infants.”[54] Specifically, RIM provided case management up to one year post-delivery, and worked to address the social, health, and behavioral health-related risk factors shown to have an impact on infant health and pregnancy outcomes.[55] Another prior use of HSI funding for prenatal care was in New Jersey, which used an HSI to support the state’s existing Supplemental Prenatal Care Program (SPCP).[56]

Case management services, which the Alabama RIM program was amended to focus on, can also assist children with a prenatal diagnosis or those with special needs.[57] Another earlier New Jersey HSI provided grants to local organizations to promote enrollment of children into the New Jersey Birth Defects and Autism Registry.[58] Once enrolled, new parents could utilize the registry to access specialized child health care management services.[59]

- Neonatal and Postnatal Home Visiting

Missouri developed an HSI that provides prenatal care management, education about newborn care, and support to high-risk families available in their homes or other settings.[60] Arkansas’ SafeCare program has provided weekly or biweekly home visits for approximately 18 to 22 weeks.[61] Maine also has had a home visiting program “for first-time families and pregnant and parenting adolescents.”[62] Massachusetts’ Healthy Families Program has provided a neonatal and postnatal home visiting program for at-risk newborns, as well as parenting education support groups.[63]

- Health Insurance and Expenses During Pregnancy and Postpartum

Several states have used HSIs to fill gaps in women’s health insurance to ensure health coverage extends through all stages of pregnancy and postpartum. Nine states have used HSIs to provide postpartum health insurance.[64] States can use HSIs to fill gaps in coverage programs. Because the American Rescue Plan Act provisions for 12 months postpartum care did not cover mothers in the From-Conception-to-End-of-Pregnancy (FCEP) or “unborn” option in CHIP, Oregon and Rhode Island used HSIs to provide them health insurance coverage.[65]

HSIs can also fill gaps in insurance coverage for children. For example, New Jersey’s Catastrophic Illness in Children Relief Fund is an HSI that assists families with unpaid medical expenses for children with catastrophic illnesses.[66]

- Parenting Training and Supplies

HSIs can be geared to help new parents. One such specialized program was the 2018 Oklahoma Safe Sleep HSI, which funded a program offering “safe sleep kits” and portable cribs to new parents, and educated on safe sleep practices to prevent Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID).[67] Additionally, Arkansas’ SafeCare HSI trains parents in infant and child health and home safety and also provides childproof safety locks, thermometers, and other learning materials.[68] Massachusetts’ 2018 Young Parent Support HSI is yet another initiative that helped organizations that provide young parents with “outreach, home visits, mentoring, and parent groups.”[69]

- Help and Assistance Hotlines

Funding specialized hotlines can help serve pregnant and postpartum women 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, during emergencies and times of unexpected need. North Carolina’s Breastfeeding Hotline HSI directs pregnant and postpartum women to lactation support resources.[70] A hotline in Massachusetts, “Child-at-Risk,” was used to identify and provide services to children who may be victims of neglect and/or child abuse.[71]

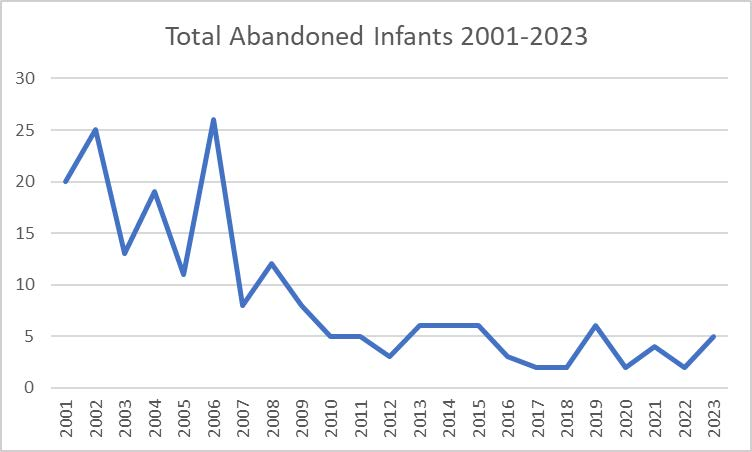

Other states could easily replicate North Carolina’s breastfeeding hotline in their own states. Pro-life hotlines not limited to breastfeeding might also be funded. Life-affirming hotlines are already offered by non-government organizations for pregnant women[72] as well as women who have had abortions.[73] Other hotlines also give pregnant and postpartum women information about designated Safe Haven locations where they are able to legally surrender their child for adoption anonymously.[74] Other resource lines could help women in crisis find the closest pregnancy resource center using directories.[75]

- Life-affirming Health Workforce

A number of HSIs focus on education and training for particular specialties in health care. For example, North Carolina offers training to obstetricians, pediatricians, and family medicine practitioners for its breastfeeding initiative.[76] New Jersey’s Nonpublic School Health Services Program funds nurses in non-public schools.[77] Life-affirming HSIs can be targeted to obstetrics, neonatologists, doulas, or other professionals providing care to pregnant women.

- School-Based Programs

Since 2022, Florida has had a School Health Services Program HSI that provides resources such as nursing assessments, individualized healthcare plans, emergency health services, medical procedures, and referrals to primary care or specialty health services. [78] States might fund similar in-school programs to serve teenage pregnant, postpartum, and parenting individuals, such as through referrals to obstetricians for prenatal care, or assistance with preparing for birth.

- Prenatal Diagnosis and Care

CMS-approved HSIs that provide resources related to prenatal diagnosis have included New Jersey’s birth defects registry[79] and Oklahoma’s sickle cell disease kits.[80] States may also fund initiatives that expand access to new life-saving treatments, such as fetoscopic laser surgery and in utero brain surgery,[81] and/or fund resources that share health information on treatment options.[82]

10. Expanding the Pro-Life Safety Net

In addition to providing pregnancy supports, HSIs can also provide wrap-around services to further expand the pro-life safety net. Previously approved HSI programs in New Jersey[83] and Oklahoma[84] have supported pediatric mental health. Similarly, Alabama’s Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Services (IECMH) program trained mental health clinicians and childcare workers on understanding trauma in young children, self-care, attachment, and other issues.[85]

Substance use treatment for pregnant and parenting women in need or their children might also be funded through HSIs.[86] To address the opioid crisis, for example, Oklahoma’s Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program for youth and young adults provided Naloxone rescue kits,[87] and the Opioid Drug Addiction and Opioid Overdose Prevention Program for Schools in New York trains school staff on how to be a responder for administering naloxone.[88]

For women who are sexually assaulted, Massachusetts established the Pediatric Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program to provide on-call, 24-hour direct psychological and health care for adolescents who have experienced this trauma.[89] Other HSIs have provided food to schools, food banks, pantries, and soup kitchens.[90] Programs can also provide child care and support for parents of children with disabilities. In 2022, New Jersey, for example, provided respite care services for children with developmental disabilities.[91]

B. Pro-Life Program Design

States seeking to strengthen their safety net for pregnant and parenting women and families in need can take a number of approaches to designing their HSIs for maximum pro-life impact.

First, HSIs can specialize in key populations in need of life-affirming resources: the unborn, pregnant and postpartum women, newborns, and those at greater risk of unplanned pregnancies. A state could create an HSI limited to geographic locations in their state where there are high rates of abortion, a large number of abortion centers, or areas where there is a shortage of obstetricians or pregnancy resource centers. States may find Alabama’s list of high-risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes and infant mortality helpful for use in drafting their State Plan Amendments; Alabama lists diabetes, hypertension, prior poor pregnancy outcomes, substance abuse, depression, abuse, interpersonal safety, lack of food, and transportation needs as just some of these risks.[92]

VI. Conclusion

HSIs offer a very flexible source of federal funding for states to expand the pro-life safety net. A pro-life HSI must fit the baseline requirements for an HSI set by the Social Security Act and CMS regulations. As long as a pro-life HSI serves low-income individuals under age 19—whether unborn, pregnant, postpartum, or parenting—it is entitled to funding. Furthermore, pro-life HSIs can be justified as serving the four categories of eligible HSIs.

To protect public health, pro-life HSIs can address the needs of children regarding access to care from fertilization to age 19. To protect the health of individuals, pro-life HSIs can be specialized to care for unborn children, newborns, or pregnant or postpartum women. The possible range of services is broad—including obstetric visits, prenatal care, case management, and safe sleep training. To improve or promote a state’s capacity to deliver public health services, pro-life HSIs can supplement or build outreach for life-affirming state or local programs or increase programs working with non-government pro-life partners. Finally, to strengthen the human and material resources necessary to accomplish public health goals relating to improving the health of children, pro-life HSIs can build up a pro-life workforce with training and coordination, and the dissemination of supplies, ranging from cribs to thermometers.

HSIs can provide a wide variety of resources that pregnant women need in order to make life-affirming decisions. States can fill gaps in federal programs, supplement existing state programs, start new state programs, or fund life-affirming, non-government partners. Using examples of past pro-life HSIs as models, states can build a stronger and broader pro-life network nationwide. More states should utilize HSIs, a highly flexible funding source, to expand the pro-life safety net.

Maya M. Noronha, J.D., is a civil rights attorney. She previously worked at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services where she developed policies to increase and improve access to $13 trillion of federally funded programs and activities to support pregnant and parenting women and their unborn and born children.

[1] Amy Pulda, “Addressing Health-Related Social Needs Using Medicaid and CHIP Flexibilities,” CMS Quality Conference 2023, 2023, https://vepimg.b8cdn.com/uploads/vjfnew/8703/content/images/1683061330may-2nd-addressing-health-related-social-needs-pdf1683061330.pdf.

[2] See Sara Hayes, “Introduction to Unlocking CHIP Funds for Home Health and Efficiency,” American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, February 16, 2022, https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/documents/Unlocking_CHIP_Funds_Slides.pdf (using a data analysis of fiscal year 2019).

[3] P.L. 105-33, 111 Stat. 561, tit. IV-J, § 4901 (Aug. 5, 1997) (adding Section 2105 to the Social Security Act, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1397ee(a)(1)(D)(ii)).

[4] Ibid.

[6] CMS, Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Health Services Initiative (January 12, 2017) (hereinafter “CMS FAQ”).

[13] New York, SPA# NY-20-0029.

[14] See, e.g., Indiana SPA # IN-17-0000-001 (approved in 2017 but effective in 2016).

[15] See CMS, CHIP Reports & Evaluations.

[16] See “Federal Financial Participation in State Assistance Expenditures; Federal Matching Shares for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and Aid to Needy Aged, Blind, or Disabled Persons for October 1, 2025, Through September 30, 2026,” 89 Fed. Reg. 94742, 94744-94745, Table 1 (Nov. 29, 2024) (comparing Enhanced Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentages (eFMAP) to regular Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) rates for fiscal year 2026 by each state).

[17] Cindy Mann, Kinda Serafi, and Arielle Traub, “Leveraging CHIP to Protect Low-Income Children from Lead,” Woodrow Wilson School of Public & International Affairs, p. 3 (Jan. 2017), https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/SHVS-Manatt-Leveraging-CHIP-to-Protect-Low-Income-Children-from-Lead-January-2017.pdf. Waivers for certain usual state plan requirements are required for Section 1115 demonstrations, which are experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects. See 42 U.S.C. § 1315.

[18] Ibid. (Noting that the requirement to provide public notice only applies when a change restricts or eliminates CHIP eligibility or benefits).

[19] Ibid. (States with CHIP-funded Medicaid expansions can receive HSI funding).

[20] See, e.g., Maryland, MD-23-0001-LEAD (Maryland submitted its State Plan Amendment for Childhood Lead Poisoning & Asthma Prevention and Environmental Case Management HSI on May 16, 2023, but CMS approved an effective date of July 1, 2022).

[21] CMS, Medicaid State Plan Amendments.

[22] See, e.g., OH-19-0014, p. 61-62 (expanding lead abatement program to add a lead-safe rental registry).

[23] See, e.g., AL-23-0027-CC, p. 1 (phasing out care coordination health services initiative).

[24] See, e.g., Massachusetts, CSPA-09-AL, p. 2 (Children’s Medical Security Plan HSI applies to children under the age of 19 with family incomes up to 400% of the FPL).

[26] Cindy Mann, Kinda Serafi, and Arielle Taub, “Leveraging CHIP to Protect Low-Income Children from Lead,” (Jan. 2017) (noting that states with CHIP-funded Medicaid expansions can receive HSI funding), https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/SHVS-Manatt-Leveraging-CHIP-to-Protect-Low-Income-Children-from-Lead-January-2017.pdf.

[29] See, e.g., “Arkansas CARTS FY2018 Report,” p. 85 (Arkansas Health & Well-Being Program for Maltreated Children Health Services Initiative is targeted to one county).

[30] See, e.g., OK CARTS FY2022 Report, pp. 68-84 (reporting on nine HSIs in 2022).

[32] See, e.g., Wisconsin SPA# WI-21-0022.

[33] CMS, Medicaid Program; Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality, 89 Fed. Reg. 41002 (May 10, 2024) (“States also have the flexibility to cover SDOH and HRSN services through CHIP Health Services Initiatives.”)

[34] HHS, Social Determinants of Health.

[35] “Rescission of Guidance on Health-Related Social Needs,” CMCS Informational Bulletin (Mar. 4, 2025).

[36] Noah Tong, “CMS rescinds Medicaid’s health-related social needs guidance,” Fierce Healthcare (Mar. 5, 2025).

[39] See, e.g., Wisconsin CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 76; Iowa SPA# IA-CHIPSPA-23, p. 12; Kentucky SPA# KY-23-0001-CHIP, p. 2; Louisiana SPA# LA-21-0026, p. 2; Maryland SPA# MD-13-001, p. 39; Nebraska SPA# NE-CSPA-06-AL; New Jersey CARTS FY2021 Report, p. 94; New York CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 85; Ohio SPA# OH-17-0038, p. 13-16; Oregon CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 64; Washington CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 57; West Virginia CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 64; Wisconsin CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 76.

[40] See, e.g., Alabama SPA# AL-23-0028-ROR; North Carolina CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 68; Oklahoma SPA# OK-23-0023.

[41] For example, Indiana, Maine, Michigan, and Ohio all adopted lead abatement programs. See Indiana SPA# IN-17-0000-0002; Maine SPA# ME-23-0025; Michigan SPA# MI-16-0017; Ohio SPA# OH-17-0038.

[42] Amy Pulda, “Addressing Health-Related Social Needs Using Medicaid and CHIP Flexibilities,” CMS Quality Conference 2023, 2023, https://vepimg.b8cdn.com/uploads/vjfnew/8703/content/images/1683061330may-2nd-addressing-health-related-social-needs-pdf1683061330.pdf.

[43] Cindy Mann, Kinda Serafi, and Arielle Taub, “Leveraging CHIP to Protect Low-Income Children from Lead,” (Jan. 2017), https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/SHVS-Manatt-Leveraging-CHIP-to-Protect-Low-Income-Children-from-Lead-January-2017.pdf.

[44] Arkansas CARTS FY2018 Report, p. 85 (Arkansas Health & Well-Being Program for Maltreated Children Health Services Initiative in one county); Alabama SPA# AL-19-0017-RIM, p. 16 (Alabama Reducing Infant Mortality in three counties).

[45] California SPA# CA-22-0031, p. 6.

[46] Alabama, SPA# AL-23-0026-RIM2.

[47] Alabama CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 70.

[48] California CARTS FY2022 Report, pp. 24, 74.

[49] Virginia CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 74.

[50] Rhode Island CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 19.

[51] Wisconsin CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 80.

[52] Alabama CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 72.

[53] CMS, CHIP Eligibility & Enrollment.

[54] Alabama SPA# AL-19-0017-RIM; Alabama SPA# AL-23-0027-CC.

[55] Alabama SPA# AL-19-0017-RIM.

[56] New Jersey SPA# NJ-17-0025.

[57] Alabama SPA# AL-23-0027-CC.

[58] New Jersey SPA# NJ-17-0025.

[59] New Jersey Department of Health, New Jersey Autism Registry.

[60] Missouri SPA# MO-20-0017; MO CARTS 2022 (p. 80).

[61] National Academy for State Health Policy, “States Use CHIP Health Services Initiatives to Support Home Visiting Programs” (Nov. 10, 2020), https://nashp.org/states-use-chip-health-services-initiatives-to-support-home-visiting-programs. Arkansas CARTS FY2022 Report. p. 64.

[62] Maine CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 78; see also Anita Cardwell, Leveraging CHIP to Improve Children’s Health: An Overview of State Health Services Initiatives (May 20, 2019).

[63] Massachusetts SPA# MA-CSPA-07-AL; see also MA CARTS 2022 (p. 86); Anita Cardwell, Leveraging CHIP to Improve Children’s Health: An Overview of State Health Services Initiatives (May 20, 2019).

[64] See Alabama SPA# AL-21-0022, California SPA# CA-21-0032, Illinois SPA# IL-CHIPSPA-8, Maine SPA# ME-23-0025, Maryland SPA# MD-23-0002, Minnesota SPA# MN-22-0001; Minnesota SPA# MN-CHIPSPA-4, Oregon SPA# OR-23-0136, Rhode Island SPA# RI-22-0026, Virginia SPA# VA-21-0027.

[65] Oregon SPA# OR-23-0136; Rhode Island SPA# RI-22-0026. Note that in 2023, Congress formally allowed states to exercise the option to extend coverage. See National Academy for State Health Policy, “State Efforts to Extend Medicaid Postpartum Coverage” (Dec. 8, 2025), https://nashp.org/state-tracker/view-each-states-efforts-to-extend-medicaid-postpartum-coverage.

[66] New Jersey SPA# NJ-17-0025, p. 13. See also New Jersey Department of Human Services, Catastrophic Illness in Children Relief Fund, https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/cicrf.

[67] Oklahoma SPA# OK-18-0001.

[68] Arkansas CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 64; Arkansas Home Visiting Network, SafeCare Arkansas.

[69] Massachusetts CARTS 2018 Report, p. 98.

[70] North Carolina SPA# NC-23-0017.

[71] Massachusetts SPA# MA-CSPA-09-AL.

[72] See, e.g., National Right to Life (877-558-0333), https://nrlc.org/help; Heartbeat International’s Option Line (800-712-HELP), https://www.heartbeatinternational.org/our-work/option-line; Care Net’s Pregnancy Decision Line (866-604-4017), https://pregnancydecisionline.org; Students for Life’s Standing with You (877-910-0096), https://www.standingwithyou.org/.

[73] See, e.g., Project Rachel (888-456-HOPE), https://hopeafterabortion.com.

[74] See, e.g., Safe Haven, (1-866-99BABY1), https://www.shbb.org/faqcontact; National Safe Haven Alliance, 1-888-510-BABY (2229), https://www.nationalsafehavenalliance.org.

[75] See, e.g., Her PLAN, https://directory.herplan.org/provider-search; BraveLove, https://www.bravelove.org/partners.

[76] North Carolina SPA# NC-23-0017, p.15.

[77] New Jersey CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 83. See also New Jersey Department of Education, Nonpublic School Health Services, https://www.nj.gov/education/nonpublic/state/health.

[78] Florida CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 68-69.

[79] New Jersey, SPA# NJ-17-0025.

[80] Oklahoma SPA# OK-18-0001.

[81] See, e.g., Paul Wagle, “Empowering Parents Following a Prenatal Diagnosis,” Lozier Institute (Aug. 1, 2025); Charlotte Lozier Institute, Five Facts About “Life-Limiting” Fetal Conditions (Feb. 15, 2024).

[82] See Heartbeat International, “Parents Facing Prenatal Diagnosis Have a New Support Resource” (Aug. 28, 2023); PrenatalDiagnosis.org.

[83] New Jersey SPA# NJ-17-0025 (New Jersey Pediatric Psychiatry Collaborative (NJPPC)).

[84] Oklahoma CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 75 (Pediatric Psychotropic Prescribing Resource Guide).

[85] Alabama SPA# AL-23-0029.

[86] See, e.g., Christopher Hull, “Strengthening the Pro-Life Safety New’s Federal Response to Perinatal Substance Use,” Lozier Institute (Jan. 22, 2025).

[87] Oklahoma SPA# OK-23-0023 (p. 9) (referring to SPA# OK-16-0007); Oklahoma Health Services Initiatives; see also Oklahoma Health Care Authority, Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) (Oct. 10, 2016).

[88] New York CARTS FY2022 Report, pp. 81-82.

[89] Massachusetts #SPA MA-CSPA-09-AL; Mass.gov, MA Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) Program.

[90] See, e.g., New York CARTS FY2022 Report, pp. 79-80 (Hunger Prevention and Nutrition Assistance Program (HPNAP)); Massachusetts SPA# MA-CSPA-07-AL (School Breakfast).

[91] New Jersey CARTS FY2022 Report, p. 80.

[92] Alabama SPA# AL-19-0017-RIM, p. 22.