The Overlooked Key to the Drop in U.S. Abortions

This is Issue 6 of the On Point Series.

For those who believe in the infallibility of contraception, a decrease in abortions means one thing: contraceptives caused the drop. Earlier this year, a Guttmacher Institute study announced a substantial, continuing drop in U.S. abortions. The study was designed to assess only two factors: whether (1) a decline in the number of abortion providers and/or (2) recent “restrictive” state laws were responsible for the declining abortion rates. But this narrow focus did not prevent the authors from concluding that contraception was responsible. Without needing to study the issue, or to substantiate this claim, the authors confidently stated that abortions declined because more women used contraception, used it more consistently, and shifted to more effective contraceptive methods.

It should be obvious that there are two ways to reduce unintended pregnancies that often lead to abortionsii:

(1) contraceptive methods of widely differing effectiveness (especially in the hands of teens)iii; and

(2) abstinence, which is always 100% effective.

If the authors had looked at the data, they would have discovered the following facts:

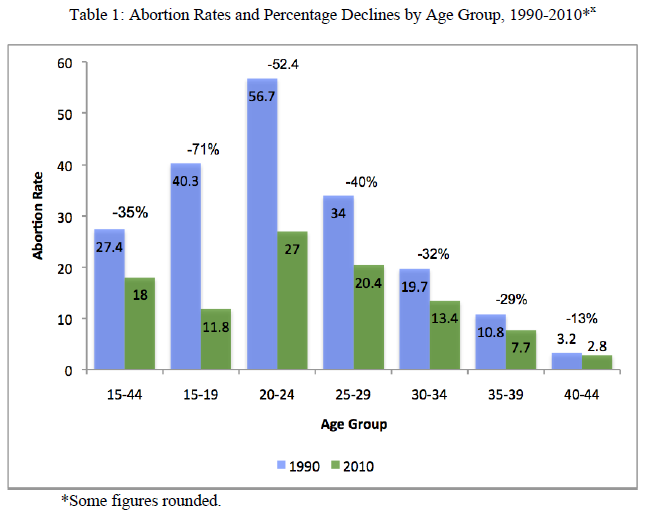

- A huge drop in teenage abortion rates is driving the overall decline in abortions. (See Table 1.)

- Teens who are “sexually active” (those who are using contraception or who have had intercourse in the preceding three months) are relying mainly on the same methods of contraception they have used for years—condoms and oral contraceptives. They have not switched en masse to effective, long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), i.e., IUDs and subdermal implants.iv So there must be another reason for their having far fewer abortions.

- The most significant change is that today more teens are remaining abstinent longer, and fewer teens are currently sexually active.v

- Despite all the assumed gains from more and better contraceptive use, the overall rate of unintended pregnancies actually increased among women—to 54/1,000 women in 2008 from 49/1,000 in 2001.vi So, apparently, “better contraceptive use” doesn’t always reduce unintended pregnancies.

- The ratio of abortions (number of abortions per 100 pregnancies, excluding miscarriages) declined—to 21.2 in 2011, from 27.4 in 1991vii—meaning that more unintended pregnancies are ending in live births rather than abortions.

To summarize, abortions are down for two main reasons: (1) 71% fewer abortions among teens (because increased abstinence equals fewer unintended pregnancies) and (2) because women 15-44 with unintended pregnancies are now 23% more likely than they were in 1991 to choose birth over abortion.

Many hard-to-quantify factors have likely contributed to the increased proportion of women with surprise pregnancies who are choosing to give birth. The technical clarity and ubiquity of ultrasounds have put a human face on unborn children. A growing body of research and the personal testimonies of women about their psychological and emotional suffering after abortion are gaining wider currency.viii Widespread media reporting of squalid clinics, maternal injuries and deaths in abortion clinics, and-public distaste for late-term abortions may be fueling a greater aversion to abortion. Several thousand pregnancy care centers are helping women access needed medical and social services, so carrying to term and raising a child no longer seems impossibly daunting. Finally, American culture no longer stigmatizes single motherhood. But what is clear—from the evidence that follows—is that more and better contraceptive use has not had a major impact on the abortion decline.

Abortion Rates

The Guttmacher researchers report a 38% drop overall in the U.S. abortion rate between 1990 and 2011—to 16.9 from 27.4 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15-44.ix The 2011 rate is the lowest since 1973 when abortion was legalized nationwide. The steepness of the decline varies considerably among different age groups, however. Between 1990 and 2010, abortion rates dropped by the following percentages among the indicated age groups:

Pregnancy rates

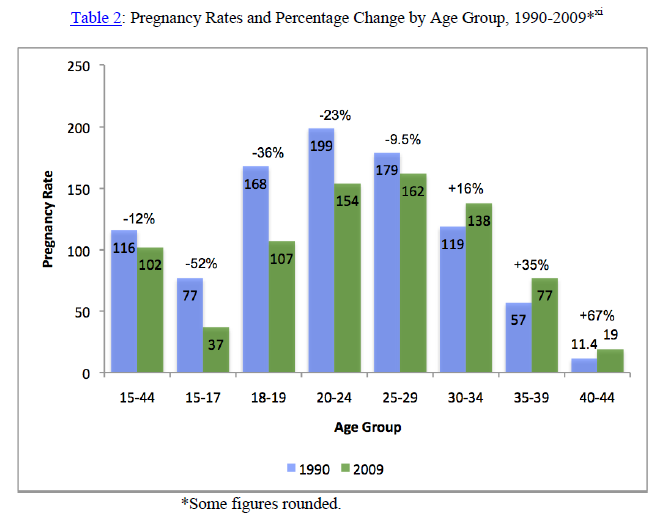

One explanation for the steep decline in abortion rates among the youngest females can be found in the change in pregnancy rates among different age groups. While there was an overall decline of 12% in pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15-44 between 1990 and 2009, once again, the youngest women experienced the steepest decline, while women in their 30s and 40s experienced increases in pregnancy rates.

Is this trend the result of teens and women in their 20s using more and better contraception than older women? No. Highly effective female sterilization is still the primary method of contraception among U.S. women in their 30s and 40s who no longer want to bear children.xii Later marriage and later child bearingxiii among U.S. women—not contraceptive failure due to user error—are the main contributing factors to the increased rates of pregnancy among women in their 30s and 40s.

But how does one account for far lower pregnancy rates among teens than among women in their 20s? Certainly a higher proportion of pregnancies in the late 20s are “intended, ”but it’s also reasonable to assume that women in their 20s who wish to avoid pregnancy will use more effective methods of contraception and use them more consistently than will teenagers. If the decline in pregnancies were caused by women switching to LARCs (costing$700-1,000), it is not likely to have occurred among teens or even among most college students who are still on their parents’ insurance policies, although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) may change that. All contraceptive methods will be “free” under the ACA and contraceptive use will be kept confidential from parents.

Use of contraceptive methods

Contraceptive use is already approaching saturation in the United States: 89% of women aged 15-44 who are at risk of pregnancy are currently using a contraceptive method; nevertheless, 51% of pregnancies are unintended.xiv

Some recent studies have organized contraceptive methods into dubiously named categories based on the method’s 12-month effectiveness rate under “typical use.” “Highly effective” methods include“ long-acting reversible contraception” (i.e., intrauterine device or hormonal implant); hormone-containing pill, patch, or ring; or injectable hormones; all with or without condoms; or sterilization of respondent or partner (which is rare for teens). Moderately effective methods include condom use alone. Less effective methods include withdrawal, emergency contraception, diaphragm….”xv

The 12-month typical use failure rates (i.e., pregnancy rates) for these “highly effective” methods are as follows xvi:

Subdermal implant- 0.05

Vasectomy (male sterilization)- 0.15

Levonorgestrel IUD- 0.2

Tubal (female) sterilization- 0.5

Copper-T IUD- 0.8

Injectable (e.g., Depo-Provera)- 6

Pill- 9

Vaginal ring- 9

Patch- 9

Clearly, the nine out of 100 women each year who become pregnant while using the pill, patch or ring (n.b., effectiveness estimates for the ring and patch are sheer guess workxvii), may not consider this method “highly effective.” Nor would one consider condom use, with a failure (pregnancy) rate of 18/100 women each year, to be “moderately effective.”xviii In a 2009 study published in Contraception, other Guttmacher researchers reported that the effectiveness rate of withdrawal is 18 pregnancies/100 women/year,xix and the condom rate, 17. It does seem arbitrary to downgrade the withdrawal method to a “less effective” rating on the basis of only one additional pregnancy per year (a difference of 5.5%), especially when “highly effective” spans an inexplicably broad range of effectiveness.

Contraceptive use among women aged 25-44 Between 1995 and 2006-2010, 2% fewer women aged 25-44 used the highly effective contraceptive methods of female and male sterilization, although sterilization remained the most widely used method among women aged 25-44 (close to 50%).

While there was no change in the percentage of pill users (20.6% of contracepting women), there was increased use of highly effective IUDs (to 5.9 percent of contracepting women aged 25-44) and increased use of “other hormonal methods” (to 5.1% of contracepting women—a wash if the switch were to patches and rings). No doubt some additional pregnancies may have been averted among women who switched from condoms or pills to IUDs and implants—at least to the extent these methods offset the drop in sterilizations, but these changes cannot begin to explain an overall 38% drop in abortions.

Contraceptive use among teens The 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance (YRBS) Reportxx states that the prevalence of only “moderately effective” condom use among the 33.7% of students who are currently sexually active increased to 60.2% in 2011, from 46.2% in 1991. Among currently sexually active students, the prevalence of contraceptive pill use “did not change significantly during 1991-2011 (declining from 20.8% to 18.0%), according to the YRBS Report. Figures were not provided for the change in use of more effective contraceptive methods (IUDs, implants, injections) between 1991 and 2011. But figures from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG)—which includes married and unmarried teens aged 15-19—did report an increase in the use of “highly effective” methods (pill, IUD, and other hormonal methods) among sexually active teens. However, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published an errata announcementxxi concerning that finding because “the analysis included some respondents who were using contraception but did not have sex during the interview month.” Excluding those students, “highly effective contraceptive use did not change significantly from 1995 … to 2006-2010….”xxii

Abstinence

The really startling change over the past decades has been in the number of teens remaining abstinent far longer than in the past.xxiii

Percentage of females who have never had sex: 1995 2006-2010 Increase in abstinence

Aged 15-19 48.9% 56.7% 16%

Aged 15-17 61.4% 72.9% 19%

Aged 18-19 28.9% 36.5% 26%

Not only are more teens remaining abstinent than ever before, but according to the 2011 YRBS, fewer also are currently sexually active—a drop of over 10%, from 37.5% of students nationwide in 1991 to 33.7% in2011.

As noted earlier, abstinence is 100% effective, i.e., the failure (pregnancy) rate of abstinence is 0.0. So even a modest uptick in abstinence will yield significant declines in unintended pregnancies and abortions. While it is true that about half of pregnancies occur among women who are sexually active and not using any form of contraception, a 2012 study sheds light on prepregnancy contraceptive use among teens with unintended pregnancies who gave birth to their children.xxiv Of the 2,321 teen moms aged 15-19 whose pregnancy was unintended, at conception 21% were using contraceptive methods that were“highly effective” when they became pregnant, 24.2% were using “moderately effective” methods at the time of conception, 5.1% were then using “less effective” methods and 49.6% were using no method. These data add context to the labels “highly” and “moderately” effective.xxv

Much more could be written about the failure of contraceptive methods to live up to their promise. But, having disproven the Guttmacher researchers’ claim that more and better contraceptive use and a switch to highly effective methods is responsible for the drop in U.S. abortions, it would be misleading to leave the impression that unintended pregnancies and abortions ought to be eliminated by permanent or “temporary female sterilization” (how some proponents refer to IUDs and implants).

A 2013 National Health Statistics Reportxxvi offers some revealing data: 99% of women aged 15-44 have used at least one contraceptive method at some point in their life; 88% have used a “highly effective, reversible method such as birth control pills, an injectable method, a contraceptive patch, or an intrauterine device.”xxvii Almost half of women have tried three or four methods;15% have tried five methods and 13% have tried six or more. Why do women switch methods so often? Generally, a lot of “user dissatisfaction.”

The pill: 30.4% of women discontinued using birth control pills. Their top reasons for discontinuing this method were: 62.9%—experiencing “side effects”; 11.8%—worried that they might have side effects; 11.5%—changes in their menstrual cycle; and 11.3% became pregnant.

Depo-Provera injection: 45.8% discontinued this method, citing the following top reasons: 74%—side effects; 30.5%—did not like changes in menstrual cycle; and 5.9%—worried they might have side effects.

Contraceptive patch: 48.5% discontinued this method, citing the following top reasons: 44.7%— side effects;11.1%—too difficult to use; 9.3%—feared the method would notwork; 9.3%— became pregnant; and 8.7%—changes in the menstrual cycle.

A 2002 Report included the following data on Norplant implant discontinuation: 41.6% of users discontinued this method, citing the following reasons: 70.6%—side effects; 19.3%—did not like changes in menstrual cycle; 9.2%—the doctor told her not to use the method again; and 8.3%—became pregnant.xxviii

If that weren’t bad enough, women using more user-independent methods of contraception (IUDs, implants, injections) more frequently forgo condom usexxix at a time when the United States is experiencing a pandemic of sexually transmitted infections and diseases (over 110,000,000 persons currently infectedxxx).

Much could also be written about the young, healthy women who have suffered strokes and fatal blood clots from using pills like Yaz and Yasmin, or Nuva ring or the Ortho Evra patch, but the reader can find all that with a simple Google search.

In the end, abstinence before marriage and monogamy may well prove to be the healthiest lifestyle of all.

i The Guttmacher Institute formerly affiliated with the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. The Institute states that one of its guiding principles is “to protect, expand and equalize universal access to information, services and rights that will enable women and men to

- avoid unplanned pregnancies;

- prevent and treat STIs, including HIV;

- exercise the right to choose safe, legal abortion.”(http://www.guttmacher.org/about/mission.html; accessed May 2, 2014).

ii “Nearly all abortions are a result of unintended pregnancy.” S. Curtin et al., “Pregnancy Rates for U.S. Women Continue to Drop, ”National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data Brief (December 2013), No. 136; p. 6, text accompanying note 7; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db136.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

iii In the first 12 months of contraceptive use,16.4% of teens will become pregnant. If the teen is cohabiting, the pregnancy (or “failure”) rate rises to 47%. Among low-income cohabiting teens, the 12-month failure rate is 48.4% for birth control pills and 71.7% for condoms. H. Fuetal., “Contraceptive Failure Rates: New Estimates from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth, “Family Planning Perspectives 31 (1999): 56-63 at 61, Tables 2 and 3; at https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/3105699.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

iv “…among sexually active high school students, use of hormonal methods (i.e., birth control pills or the injectable contraceptive Depo-Provera), alone or in combination with condoms, remains low. Among teens,15-19 years, use of LARCs (i.e., intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants), remains rare.”K. Pazoletal. “Vital Signs: Teen Pregnancy—United States, 1991-2009, ”Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (“MMWR”)(April 8, 2011); 60: 13; at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6013.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

v Between 1988 and 2006-2010, the percentage of never-married females who have ever had sexual intercourse dropped to 43% from 51%; during that time period, the percentage of never-married males who have ever had sexual intercourse dropped to 42% from 60%. G.M. Martinez et al., “Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth, ”NCHS Vital and Health Statistics (October 2011) 23: 31. See Tables 2 and 3 for reduced frequency of sexual activity; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_031.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

vi “…between 2001 and 2008, the unintended pregnancy rate increased from 49 to 54 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15-44, and the proportion of pregnancies that were unintended increased from 48% to 51%. ”R.K. Jones and J. Jerman, “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2011,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health (2014); 46: 1; https://guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/psrh.46e0414.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

vii R.K. Jones and J. Jerman, note 6 supra; see Table 1.

viii See, e.g., www.hopeafterabortion.org; accessed April 29, 2014.

ix R.K. Jones and J. Jerman, note 6 supra.

x Figures for 1990 are from Table 2, National Vital Statistics Reports, (October 14, 2009), 58: 4; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_04.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014. Figures for 2010 are from Table 4, K. Pazol et al., “Abortion Surveillance—United States, 2010, ”MMWR Surveillance Summaries (Nov. 29, 2013) 62: 1-44; at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss6208a1.htm; accessed April 29, 2014.

xi Figures for 1990 are from Table 2, National Vital Statistics Reports, (October 14, 2009), 58: 4; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_04.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014. Figures for 2009 are from S.C. Curtin et al., note 2; see Figure 1.

xii Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception for women aged 30-34 (30%), 35-39 (37%) and 40-44 (51%). J. Jones et al., “Current Contraceptive Use in the United States, 2006-2010, and Changes in Patterns of Use Since 1995, ”NCHS National Health Statistics Reports (October 18, 2012), No. 60; Figure2; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr060.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

xiii T.J. Mathews and B.E. Hamilton, “Delayed Childbearing: More Women Are Having their First Child Later in Life, ”NCHS Data Brief (August 2009); 21: 1-8; at http://blogs.sgmcb.com/glassceilinggrubbyfloor/research/NHCS%20Data%20Brief%2021%20–%20Delayed%20Childbearing.pdf;accessedApril29,2014.

xiv J. Jones et al., note 12 supra, Table 3; R.K. Jones and J. Jerman, note 6.

xv G.M. Martinez et al., “Sexual Experience and Contraceptive Use among Female Teens–United States,1995, 2002, and 2006-2010,” MMWR (May 4, 2012) 61: 17, at 299; at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6117.pdf; accessed April 29, 2014.

xvi Guttmacher Institute, Fact Sheet “Contraceptive Use in the United States (August 2013); at http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_contr_use.html; accessed April 29, 2014.

xvii “Numbers for typical use failure of Ortho Evra and Nuva Ring are not based on data. They are estimates based on pill data. ”M. Zieman et al., A Pocket Guide to Managing Contraception (Tiger, GA: Bridging the Gap Foundation) 2010. See notes to Table 13.2.

xviii R.K. Jones et al., “Better than Nothing or Savvy Risk-Reduction Practice? The Importance of Withdrawal, ”Commentary, Contraception 79 (2009) 407-410; at http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/reprints/Contraception79-407-410.pdf; accessed April 29

xix R.K. Jones et al., note 18.

xx D.K.Eaton et al., “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance–United States, 2011,” MMWR Surveillance Summaries (June 8, 2012) 61: 4; at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6104.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxi MMWR (October 26, 2012) 61: 42 at 864; http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm6142.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxii MMWR (October 26, 2012), note 21 supra.

xxiii G.M. Martinez et al., note 15 supra.

xxiv A.T. Harrison et al., “Prepregnancy Contraceptive Use among Teens with Unintended Pregnancies Resulting in Live Births—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), 2004-2008,” MMWR (Jan. 20, 2012) 61: 2; at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm6102.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxv A.T. Harrison et al., note 24 supra. See Table 2.

xxvi K. Daniels et al., “Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 1982-2010, ”National Health Statistics Reports (Feb. 14, 2013) 62; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr062.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxvii K. Daniels et al., note 26 supra.

xxviii A. Chandra et al., “Fertility, Family Planning, and Reproductive Health of U.S. Women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth,” NCHS Vital Health Stat (2005) 23: 25; at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_025.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxix K. Pazol et al., “Condoms for Dual Protection: Patterns of Use with Highly Effective Contraceptive Methods,” Public Health Rep. (Mar-Apr 2010); 125 (2): 208–217; at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2821848/pdf/phr125000208.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.

xxx http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/sti-estimates-fact-sheet-feb-2013.pdf; accessed May 1, 2014.