Studies Confirm: Legalizing Physician-Assisted Suicide Does Not Save Lives

By Caitlyn Axe

Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is promoted as a compassionate response to the suffering of terminally ill individuals. Opponents of PAS recognize the practice as anything but compassionate. Debates surrounding the legalization of PAS invoke questions and theories about the effect of legalizing physician-assisted suicide on the prevalence of suicide in all its forms.[1] Society in large part strives to prevent suicide, and the “social contagion” effect of publicizing or popularizing suicide is widely known as antithetical to the goal of suicide prevention.

Normalizing physician-assisted suicide as an acceptable form of “care” raises concerns about promoting suicide when we aim to prevent it. Advocates for life argue that medically sanctioned suicide, promoted as acceptable and even honorable, will increase the number of lives lost. Contrary to concerns about promoting suicide, proponents of PAS theorize that legalizing physician-assisted suicide will, in fact, prevent suicide.[2] While it seems like a prime example of cognitive dissonance, the idea that physician- assisted suicide saves lives has been circulated in draft bills and the Supreme Court of Canada to support PAS legislation. Such a claim warrants rigorous critique.

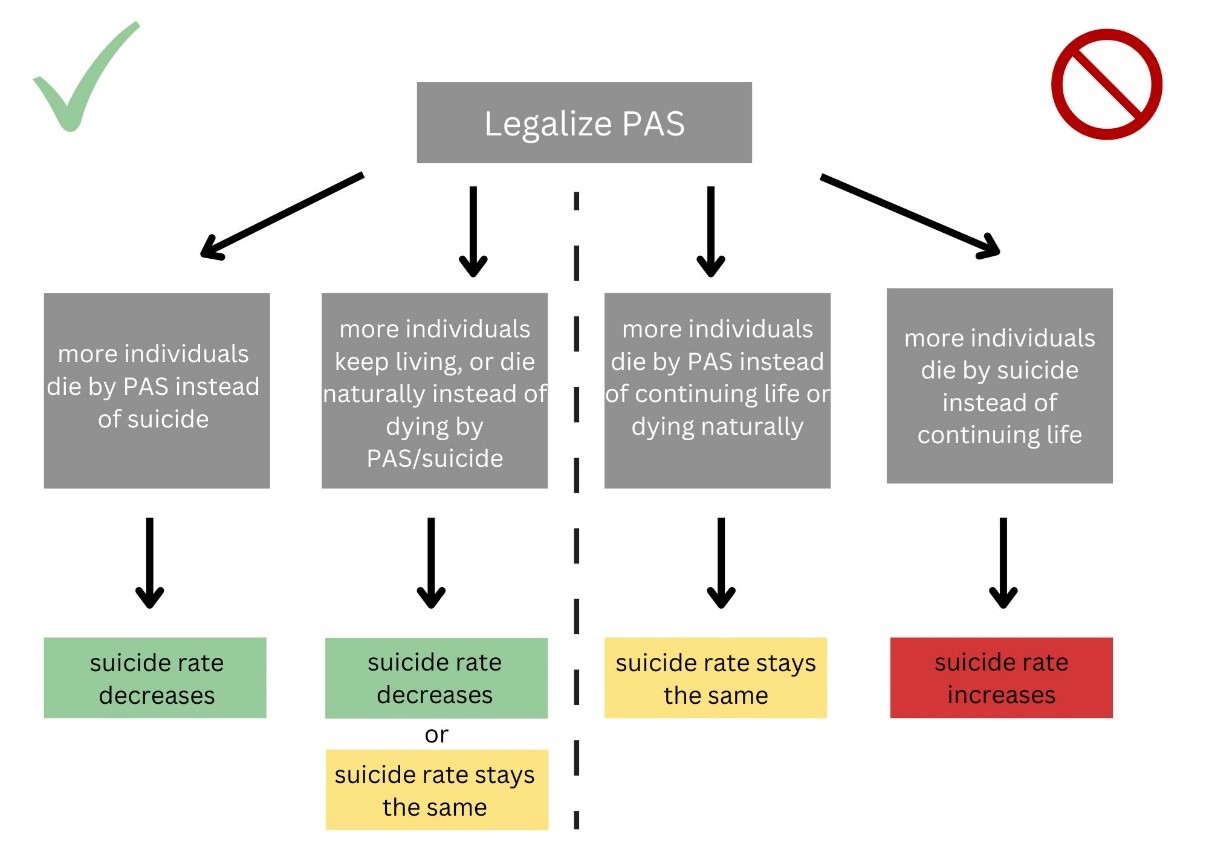

Proponents of PAS argue that legalization of physician-assisted suicide will decrease suicide deaths. The idea behind this seeming paradox is two-fold. The first premise underlying the idea is that individuals who would have committed suicide, were PAS not an option, will instead end their lives by physician-assisted suicide. The second premise is that individuals, comforted by the knowledge that PAS is an option, may decide to continue living with the assurance that a “way out” is available should they need it. If true, these premises should be corroborated by a measurable decrease in suicide rates.

Image 1: Two theories of the impact of legalizing PAS on suicide deaths. The gray boxes indicate hypothetical responses to the availability of PAS and the boxes below indicate the quantifiable outcomes if the hypothetical changes in behavior were actualized.

The relationship between legal PAS and suicide is quantifiable. Do suicide rates change following the legalization of PAS? Are suicide rates in regions where PAS is legal higher than in their counterparts where it is not? These are central questions and yet there are relatively few studies examining their answers. In fact, a 2022 systematic literature review of the topic sorted through over 10,000 papers and found only six studies worthy of inclusion. The literature review, titled Investigating the relationship between euthanasia and/or assisted suicide and rates of non-assisted suicide, is the first to compile literature on the impact of legalizing physician-assisted suicide on suicide rates as a whole.

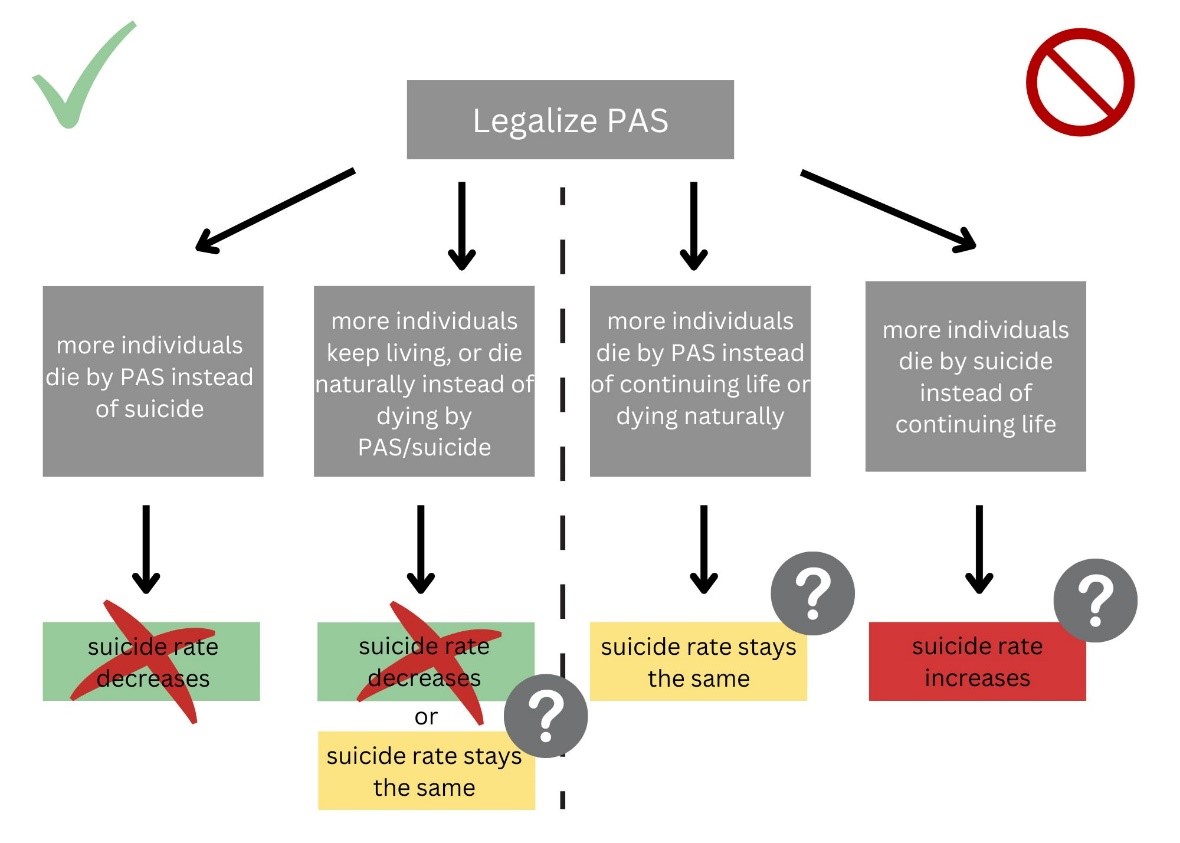

The included studies examined suicide and PAS (and/or euthanasia) in the Netherlands and Belgium. While the studies employed various methods of analysis, none provided evidence of a decrease in suicide rates associated with the introduction of PAS (or euthanasia). Several of the studies indicated a positive association between PAS (or euthanasia) and suicide rates, but the associations were not statistically significant. Two studies using data from the Swiss National Cohort revealed an overrepresentation of women in deaths by PAS (or euthanasia) and disparately increasing rates of death by PAS (or euthanasia) among elderly women in particular.[3] A study using 20 years of reported data from Oregon revealed similar increases in rates of suicide and PAS among elderly women.

A study asking Is assisted suicide a substitution for unassisted suicide? was published around the same time as the systematic literature review with the aim of further quantifying the theory that PAS decreases suicide. The authors of this study used both an event study approach and a synthetic control method for states where PAS is legal or decriminalized. The study established a significant increase in self-initiated deaths associated with legalization of assisted suicide, where self-initiated deaths refer to the combined total of suicide and PAS deaths. In line with the findings of the systematic literature review, the authors found no evidence of a decrease in suicide rates following legalization of assisted suicide. Similar to trends in the literature review, the suicide rates of women were more impacted by legalization of PAS than those of men.

While a prime example of cognitive dissonance, the proposal that PAS prevents suicide is also a display of the common conviction that suicide, deaths that could have been avoided, and deaths that could have been postponed are all tragedies to be prevented. Those who oppose physician-assisted suicide simply uphold this conviction to its fullest by recognizing that every human life is worthy of protection and care. It is hypocritical to prevent self-inflicted death but promote self-initiated death and far more hypocritical to promote one for the sake of preventing the other.

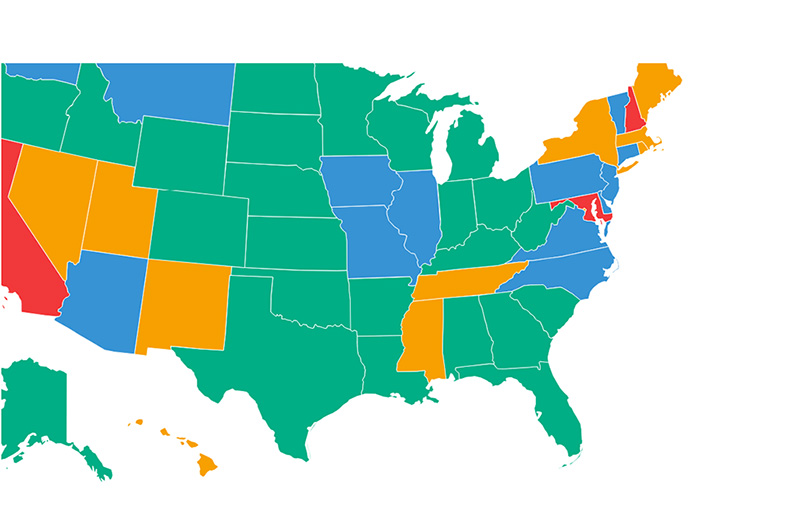

Image 2: The two theories can be evaluated based on what studies reveal about measurable changes in suicide rates. Red crosses indicate that there is no evidence of the outcome. Question marks indicate that there is either no evidence to contradict the outcome or no significant evidence to support it.

Caitlyn Axe is an intern for the Charlotte Lozier Institute and is co-author of a peer-reviewed study entitled, “Investigating the relationship between euthanasia and/or assisted suicide and rates of non-assisted suicide: systematic review,” published in BJPysch Open.

[1] In this discussion, suicide and PAS will be referred to as two distinct practices, although there is much to be said for their relatedness.

[2] See https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_resources/documents/a-to-z/p/Posner96.pdf. Richard Posner details a hypothesis about the utility of legalizing assisted suicide.

[3] For the other study, please see: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26743810/