The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013: The Sweeping Impact of S. 1696

by Thomas M. Messner, J.D.

Download PDF here: The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013: The Sweeping Impact of S. 1696

United States Senator Richard Blumenthal introduced S. 1696 on November 13, 2013. Cosponsors of the bill currently include Senators Baldwin, Boxer, Schatz, Hirono, Harkin, Whitehouse, Sanders, Schumer, Murray, Gillibrand, Cantwell, Murphy, Brown, Warren, Tester, Menendez, Heinrich, Coons, Markey, Merkley, Shaheen, Mikulski, Booker, Feinstein, Stabenow, Wyden, Franken, Klobuchar, Cardin, McCaskill, Begich, Baucus, Durbin, Walsh, and Levin.

S. 1696 proposes a federal law that would be titled “The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013.”

If enacted in current form, S.1696 would jeopardize or outright invalidate a wide range of State and Federal abortion-related regulations. In particular, S. 1696:

- Could Be Interpreted to Impose a Heightened Burden of Proof on Many if Not Most Abortion Laws Ever Enacted

- Would Trump 20-Week Laws in a Very Large Percentage of Cases

- Would Create a Special Protection in Federal Law for Sex-Discrimination Abortion

- Would Jeopardize Laws Limiting Performance of Abortions to Licensed Physicians

- Would Authorize Federal Court Attacks on Abortion Clinic Health and Safety Standards that Protect Women

- Could Have the Effect of Deterring Health and Safety Inspections of Abortion Clinics

- Would Jeopardize Limits on Late Abortions

- Would Jeopardize Prohibitions on Taxpayer-Funded Abortion—Including the Hyde Amendment—as well as Abortion Training

- Would Jeopardize Health and Safety Regulations Governing the Use of Abortion Drugs

- Would Jeopardize Health and Safety Regulations Governing the Practice of Telemedicine Abortion

- Would Jeopardize Sonogram and Fetal Heartbeat Test Requirements

- Would Jeopardize Mandatory Reflection Periods that the U.S. Supreme Court Has Upheld

- Could Be Interpreted to Trump State and Federal Conscience Protections

S. 1696 does not apply to laws regulating physical access to clinic entrances, requirements for parental consent or notification before a minor may obtain an abortion, insurance coverage of abortion, or partial-birth abortion.

Brief Overview of S. 1696

S. 1696 contains eight sections. Section 4 contains the substantive provisions of S. 1696. Section 4 is titled “Prohibited Measures and Actions.”

Section 4 contains three basic types of prohibitions. One type of prohibition involves direct prohibitions. A second type of prohibition involves conditional prohibitions. A third type of prohibition involves a heightened burden of proof that must be satisfied if a showing of prima facie unlawfulness is made.

The standards for making a prima facie showing of unlawfulness and, where such a showing is made, for satisfying the heightened burden of proof are set forth in Section 4(b). Section 4(b) requires extended analysis. Analysis of Section 4(b) follows in a separate section of this paper titled “S. 1696 Could Be Interpreted to Impose a Heightened Burden of Proof on Many if Not Most Abortion Laws Ever Enacted.”

A brief restatement of the other two types of prohibitions, direct prohibitions and conditional prohibitions, follows here.

Direct prohibitions include Section 4(a)(6), Section 4(c)(1), Section 4(c)(2), Section 4(c)(3), and Section 4(c)(4).

- Under Section 4(c)(1), “[a] prohibition or ban on abortion prior to fetal viability” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(c)(4), “[a] measure or action that prohibits or restricts a woman from obtaining an abortion prior to fetal viability based on her reasons or perceived reasons or that requires a woman to state her reasons before obtaining an abortion prior to fetal viability” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(6), “[a] requirement that, prior to obtaining an abortion, a woman make one or more medically unnecessary visits to the provider of abortion services or to any individual or entity that does not provide abortion services” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(c)(2), “[a] prohibition on abortion after fetal viability when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating physician, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant woman’s life or health” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(c)(3), “[a] restriction that limits a pregnant woman’s ability to obtain an immediate abortion when a health care professional believes, based on her or his good-faith medical judgment, that delay would pose a risk to the woman’s health” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

Conditional prohibitions include Section 4(a)(1), Section 4(a)(2), Section 4(a)(3), Section 4(a)(4), Section 4(a)(5), and Section 4(a)(7). In each of the following restatements emphasis is added to the conditional clause in the prohibition.

- Under Section 4(a)(1), “[a] requirement that a medical professional perform specific tests or follow specific medical procedures in connection with the provision of an abortion, unless generally required for the provision of medically comparable procedures,” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(2), “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to delegate tasks, other than a limitation generally applicable to providers of medically comparable procedures,” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(3), “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to prescribe or dispense drugs based on her or his good-faith medical judgment, other than a limitation generally applicable to the medical profession,” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(4), “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to provide abortion services via telemedicine, other than a limitation generally applicable to the provision of medical services via telemedicine,” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(5), “[a] requirement or limitation concerning the physical plant, equipment, staffing, or hospital transfer arrangements of facilities where abortions are performed, or the credentials or hospital privileges or status of personnel at such facilities, that is not imposed on facilities or the personnel of facilities where medically comparable procedures are performed” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

- Under Section 4(a)(7), “[a] requirement or limitation that prohibits or restricts medical training for abortion procedures, other than a requirement or limitation generally applicable to medical training for medically comparable procedures,” is “unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government.”

The term “medically comparable procedures” appears in Section 4(a)(1), Section 4(a)(2), Section 4(a)(5), and Section 4(a)(7). S. 1696 fails to define the term “medically comparable procedures.” How courts interpret that term will have considerable significance for the legal effects created by the four provisions where the term appears. A brief treatment of the term here will facilitate analysis of those four provisions throughout the paper.

Some parties will argue, correctly, that no “procedure” is “medically comparable” to abortion. As the Supreme Court has explained, “Abortion is inherently different from other medical procedures, because no other procedure involves the purposeful termination of a potential life.”[1] However, applying this understanding to S. 1696 would render ineffective the four provisions of S. 1696 where the term appears. And that approach would violate “one of the most basic interpretive canons, that [a] statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant.”[2] It is the “duty” of courts “to give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute.”[3] “[E]ach word in a statute should [carry meaning].”[4] In addition to these general rules, Section 5 of S. 1696 commands courts to “liberally construe” the provisions of S. 1696 to effectuate its purposes. Analysis of S. 1696 as currently drafted should be based upon the assumption that courts interpreting it are likely to conclude that one or more procedures are, within the meaning of S. 1696, “medically comparable” to abortion. Moreover, because Section 3(1) of S. 1696 defines the term “abortion” to include “any medical treatment, including the prescription of medication, intended to cause the termination of a pregnancy,” courts interpreting the term “medically comparable procedures” must consider procedures that would be “medically comparable” to medication abortions, surgical abortions, or both, depending on the particular use of the term in each of the four provisions where it appears.

Finally, a few additional notes will help to understand the potential scope and impact of S. 1696.

First, S. 1696 would apply to both State and Federal laws. Section 4(a) and Section 4(c) both refer to unlawful restrictions that “shall not be imposed or applied by any government.” Section 3(3), in turn, defines the term “government” to include “a branch, department, agency, instrumentality, or individual acting under color of law of the United States, a State, or a subdivision of a State.” Government restrictions subject to S. 1696 would include, as set forth in Section 4(e), statutory and other restrictions whether enacted or imposed prior to or after the date of enactment of S. 1696.

Second, as set forth in Section 4(d), S. 1696 does not apply to “laws regulating physical access to clinic entrances, requirements for parental consent or notification before a minor may obtain an abortion, insurance coverage of abortion, or the procedure described in section 1531(b)(1) of title 18, United States Code.” Section 1531(b)(1) of title 18 of the United States Code describes the procedure known as partial-birth abortion.

Third, Section 5 is titled “Liberal Construction.” It states, “In interpreting the provisions of this Act, a court shall liberally construe such provisions to effectuate the purposes of the Act.” Section 2(b) is titled “Purpose.” It states that the “purpose” of S. 1696 is “to protect women’s health by ensuring that abortion services will continue to be available and that abortion providers are not singled out for medically unwarranted restrictions that harm women by preventing them from accessing safe abortion services.”

Fourth, Section 3 of the Act defines seven terms including “abortion,” “abortion provider,” “government,” “health care professional,” “pregnancy,” “state,” and “viability.” Section 3 does not define other terms used in S. 1696 including “health,” “medically unnecessary,” “good-faith medical judgment,” and “medically comparable procedures.”

S. 1696 Could Be Interpreted to Impose a Heightened Burden of Proof on Many if Not Most Abortion Laws Ever Enacted

Section 4(b) of S. 1696 would make certain measures and actions unlawful unless, as set forth in Section 4(b)(4), the government “establishes, by clear and convincing evidence” that the measure or action “significantly advances the safety of abortion services or the health of women” and the safety of abortion services or the health of women “cannot be advanced by a less restrictive alternative measure or action.” Plaintiffs such as Planned Parenthood could trigger this heightened burden of proof by establishing a prima facie case that a measure or action is unlawful under Section 4(b). To establish a prima facie case of unlawfulness, plaintiffs would need to make only one of two showings. Under Section 4(b)(2)(A) plaintiffs could make a prima facie case of unlawfulness by showing that the measure or action “singles out the provision of abortion services or facilities in which abortion services are performed.” Or under Section 4(b)(2)(B) plaintiffs could make a prima facie case of unlawfulness by showing that the measure or action impedes access to abortion services based on “one or more” of seven factors set forth in Section 4(b)(3).

The potential scope of Section 4(b) would be extremely wide and, depending on the facts of the case and how courts interpreted certain provisions of Section 4(b), could reach an extensive range of State and Federal abortion-related laws and regulations. For every measure or action that would fall within the scope of Section 4(b), the government would be required, under Section 4(b)(4), to demonstrate, by clear and convincing evidence, that the measure or action “significantly advances” the safety of abortion services or women’s health and is the least restrictive way of doing so. Failure to satisfy this heavy burden would result in the measure or action being enjoined under S. 1696, as set forth in Section 6(c). Further, under Section 6(d), S. 1696 would force taxpayers to pay the costs of litigation for plaintiffs such as Planned Parenthood who prevail or even “substantially prevail” in actions brought under S. 1696.

Heightened Burden of Proof Under “Singles Out” Clause of Section 4(b)(2)(A)

Section 4(b)(2)(A) provides the first of the two methods for triggering the heightened burden of proof. Section 4(b)(2)(A) provides that a plaintiff can make a prima facie showing of unlawfulness by demonstrating that the challenged measure or action “singles out the provision of abortion services or facilities in which abortion services are performed.”

Section 4(b)(2)(A) yields at least two potential interpretations. The first potential interpretation is that a law “singles” out abortion services and therefore triggers the heightened burden of proof by specifically addressing the subject of abortion either by itself or with one or more other subjects. Under this interpretation abortion laws would be subject to the heightened burden of proof even if they merely applied a general standard to a matter involving abortion but did so in a “measure” or “action” that addressed abortion specifically. Under this interpretation of Section 4(b)(2)(A) any law, regulation, or government action specifically addressing abortion would be subject to the heightened burden of proof and would be upheld only upon a demonstration, made by clear and convincing evidence, that the measure or action significantly advanced the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible.

The second approach to interpreting “singles out” is not as formalistic but would still be very broad. Under the second approach, potential interpretations of “singles out” include that a measure or action “singles out” abortion services or abortion facilities if that measure or action applies a standard to abortion services or abortion facilities that is not applied to any other services or facilities, that is not applied to all other similarly situated services or facilities, or that is applied to some or all other similarly situated services or facilities but with certain variations in the abortion context. Though not as extreme as the first approach to interpreting “singles out,” this second approach would likewise jeopardize a wide range of abortion-related regulation.

Under either interpretation, the “singles out” standard would significantly distort regulatory approaches to abortion-related issues at both the State and Federal levels. In some instances, laws that regulate abortion might simply be designed to elevate the standards of abortion services or abortion facilities to the standards achieved by other regulated health care providers and facilities. In many cases, however, laws that regulate abortion might take into account and reflect the unique nature of abortion in the life of women and their unborn children, in the practice of medicine, and in society as a whole. In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, abortion is a “unique act”[5] and “inherently different” from other medical procedures.[6] Therefore it is no surprise, as explained by a Federal appeals court, that “[t]he rationality of distinguishing between abortion services and other medical services when regulating physicians or women’s healthcare has long been acknowledged by Supreme Court precedent.”[7] Indeed, even as a general rule, aside from the particular and unique nature of abortion, policymakers might conclude that the most uniform method of regulating medical procedures is to regulate them differently according to the unique issues presented by the procedures or practice area. Non-ideological, evidence-based standards of care and practice that make sense in one context might very well be unjustified, irrational, or even counterproductive in another context. Even if abortion were not unique in the field of medicine and in society as a whole, regulating abortion based on the particular issues it presents would simply correspond with a sensible approach to regulating for public health and safety in general.

S. 1696 runs against this commonsense approach. Instead of allowing for a flexible, evidence-based approach to regulating abortion-related issues based on the unique issues abortion presents, S. 1696 would impose a broad, indiscriminating burden that, ironically, would “single out” abortion for special protections under the rubric of targeting measures that “single out” abortion.

Heightened Burden of Proof Under “Impedes” Clause of Section 4(b)(2)(B) and Seven Factors Described in Section 4(b)(3)

Section 4(b)(2)(A) provides the first method for establishing a prima facie case of unlawfulness under S. 1696. Section 4(b)(2)(B) provides the second method.

Under Section 4(b)(2)(B) a plaintiff may make a prima facie showing of unlawfulness by demonstrating that the measure or action challenged “impedes women’s access to abortion services based on one or more of the factors described in” Section 4(b)(3). Section 4(b)(3), in turn, sets forth seven factors “for a court to consider in determining whether a measure or action impedes access to abortion services.” The Section 4(b)(2)(B) showing may be made based on “one or more” of these factors.

Section 4(b)(2)(B) fails to clarify the relationship between Section 4(b)(2)(B) and Section 4(b)(3). Courts could conclude that, for the purpose of establishing a prima facie showing of unlawfulness under Section 4(b)(2)(B), a measure or action “impedes” access to abortion, without any further factual showing, so long as it comes within the meaning of “one or more” of the factors described in Section 4(b)(3). Or courts could conclude that, to establish a prima facie case under Section 4(b)(2)(B), plaintiffs must show that a measure or action, in fact, impedes access to abortion and, separately, comes within the meaning of “one or more” of the factors described in Section 4(b)(3). The first reading would be broader than the second reading. However, even the second reading could produce a broad scope of application depending on the interpretation courts gave to the term “impedes,” especially in the light of Section 5, which commands courts to “liberally construe” provisions of S. 1696 to “effectuate” its purposes. Analysis of S. 1696 should be based on the broadest, not the narrowest, potential interpretations of its provisions. But either understanding of the relationship between Section 4(b)(2)(B) and Section 4(b)(3) could produce a sweeping scope of application.

The Section 4(b)(3) factors “for a court to consider in determining whether a measure or action impedes access to abortion services” for purposes of Section 4(b)(2)(B) include:

- Section 4(b)(3)(A) states “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.”

- Section 4(b)(3)(B) states “[w]hether the measure or action is reasonably likely to delay some women in accessing abortion services.”

- Section 4(b)(3)(C) states “[w]hether the measure or action is reasonably likely to directly or indirectly increase the cost of providing abortion services or the cost for obtaining abortion services (including costs associated with travel, childcare, or time off work).”

- Section 4(b)(3)(D) states “[w]hether the measure or action requires, or is reasonably likely to have the effect of necessitating, a trip to the offices of the abortion provider that would not otherwise be required.”

- Section 4(b)(3)(E) states “[w]hether the measure or action is reasonably likely to result in a decrease in the availability of abortion services in the State.”

The potential scope of regulation covered by these factors would be enormous. In particular, two of the Section 4(b)(3) factors, Section 4(b)(3)(A) and Section 4(b)(3)(C), are so broadly worded that they could be interpreted to reach a potentially very large swath of abortion-related regulation. These provisions provide astonishing “trump cards” for abortion providers to challenge a host of abortion regulations based on potentially nothing more than the assertion that the regulation “interferes” with the provider’s ability to provide abortion services “in accordance with” her or his “good-faith medical judgment” or would be “reasonably likely” to increase, “directly or indirectly,” the cost of providing or obtaining an abortion. The potential effects of these provisions are so broad that the provisions could even result in heightened judicial scrutiny of State and Federal laws that have nothing to do with abortion services directly but that somehow “interfere” with an abortion provider’s “ability” to “render services” “in accordance with” her or his “good-faith” medical judgment or increase the costs, “directly or indirectly,” of providing or obtaining an abortion. At a minimum these provisions would provide a statutory basis for generating a huge amount of litigation.

S. 1696 Would Trump 20-Week Laws in a Very Large Percentage of Cases

Twenty-week laws prohibit elective abortion, subject to specified exceptions, at or after 20 weeks of pregnancy. Several States have enacted 20-week laws in recent years and the U.S. House of Representatives passed a national 20-week bill in 2013.[8]

Twenty-week laws protect unborn children from suffering pain. The 20-week bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives found that “there is substantial medical evidence that an unborn child is capable of experiencing pain at least by 20 weeks after fertilization, if not earlier.”[9] Twenty-week laws also advance women’s health. According to Americans United for Life, “[A] woman seeking an abortion at 20 weeks is 35 times more likely to die from abortion than she was in the first trimester” and at “21 weeks or more, she is 91 times more likely to die from abortion than she was in the first trimester.”[10]

S. 1696 would trump State 20-week laws in a large percentage of cases. Section 4(c)(1) states that a “prohibition or ban on abortion prior to fetal viability” is unlawful and shall not be imposed or applied by any government. Section 3(7) of S. 1696 defines viability as “the point in a pregnancy at which, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating health care professional, based on the particular facts of the case before her or him, there is a reasonable likelihood of sustained fetal survival outside the uterus with or without artificial support.” In most instances a 20-week law will apply before viability occurs. Twenty weeks can be measured in different ways including from the first day of the last menstrual cycle (LMP) and from the point of fertilization. (“The LMP age is the post-fertilization age, plus two weeks.”[11]) Viability can occur at 20 weeks post-fertilization age;[12] in the current state of medical technology, however, viability will occur later than 20 weeks post-fertilization age in a very large percentage of cases.[13] Where a 20-week prohibition on elective abortion applies before viability occurs, S. 1696 would trump the 20-week rule and require the availability of elective abortion.

Other provisions of S. 1696 would threaten 20-week laws whether those laws applied before or after viability. Section 4(c)(2) makes unlawful “[a] prohibition on abortion after fetal viability when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating physician, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant woman’s life or health.” S. 1696 does not define the term “health.” If courts construe the health exception set forth in Section 4(c)(2) more broadly than the health exception set forth in a particular 20-week law, either on the ground that S. 1696 contemplates a very broad understanding of the term “health” or reserves that determination to the “good-faith medical judgment” of the abortionist, then S. 1696 would reduce the effective scope, potentially significantly, of that 20-week policy.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “impedes” access to abortion services based on “one or more” of the factors described in Section 4(b)(3). The Section 4(b)(3) factors include Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.” Some courts might rule that 20-week laws “interfere” with the ability of doctors to provide abortions “in accordance with” their “good-faith medical judgment.” States would then be forced to establish by clear and convincing evidence that such laws “significantly” advanced the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible. The heightened burden of proof imposed by Section 4(b) makes no allowance for States’ interest in protecting unborn children from pain.

Section 2(a)(4) of S. 1696 states that “bans on abortions prior to viability” are “blatantly” unconstitutional. That assertion misleads. In a much noted 2013 ruling a Federal appellate court struck down as unconstitutional a State law prohibiting elective abortion at 20 weeks in LMP age.[14] But the U.S. Supreme Court has never decided a challenge to a 20-week law. And there are substantial reasons to believe that the Court might very well uphold 20-week laws as constitutional.[15] However, if S. 1696 became law, the Court would have no occasion to decide that constitutional question. As a general rule, federal courts “will not pass upon a constitutional question . . . if there is also present some other ground upon which the case may be disposed of. . . . Thus, if a case can be decided on either of two grounds, one involving a constitutional question, the other a question of statutory construction or general law, the Court will decide only the latter.”[16] Because S. 1696 would trump 20-week laws even if the Constitution permits 20-week laws, in a legal challenge to 20-week laws courts would not decide the constitutional question. S. 1696 would effectively freeze further jurisprudential developments regarding the constitutional validity of 20-week laws.

S. 1696 Would Create a Special Protection in Federal Law for Sex-Discrimination Abortion

S. 1696 would protect the practice of sex-discrimination abortion, race-discrimination abortion, and disability-discrimination abortion. Sex-discrimination abortion is when an abortion is conducted because of the sex of the unborn child. Race-discrimination abortion is when an abortion is conducted because of the race of the unborn child. Disability-discrimination abortion is when abortion is conducted because the unborn child suffers from a condition such as Down syndrome.

Several States have already enacted regulations addressing the practice of abortions based on the sex, race, or disability of the child or one or more of those bases of discrimination.[17] And more States might enact similar legislation in coming years. According to Americans United for Life, in 2013 “at least 16 States considered measures to prohibit abortion based on the child’s sex, race, and/or diagnosed genetic abnormality.”[18]

S. 1696 would wipe out State laws prohibiting the practice of discrimination abortion. Section 4(c)(4) makes unlawful “[a] measure or action that prohibits or restricts a woman from obtaining an abortion prior to fetal viability based on her reasons or perceived reasons or that requires a woman to state her reasons before obtaining an abortion prior to fetal viability” (emphasis added).

Section 4(c)(4) is a clear-cut prohibition on laws that prohibit the practice of sex-selection abortion as well as abortions performed for the reason of the child’s race or genetic condition such as Down syndrome. S. 1696 would write a special protection into the U.S. Code for discriminating against unborn children on any ground, including sex, race, and disability.

S. 1696 Would Jeopardize Laws Limiting Performance of Abortions to Licensed Physicians

The U.S. Supreme Court has made, in its own words, “repeated statements” that “the performance of abortions may be restricted to physicians.”[19] However, S. 1696 would jeopardize the ability of the States to restrict the performance of abortions to licensed physicians.[20]

Section 4(a)(2) of S. 1696 makes unlawful “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to delegate tasks, other than a limitation generally applicable to providers of medically comparable procedures.” S. 1696 does not define the term “medically comparable procedures,” but Section 3(1) defines abortion to include surgical abortion procedures as well as medication abortion procedures that involve a patient consuming prescription drugs. If a court concluded that any procedure involving a patient consuming prescription drugs was “medically comparable” to abortion, then the potential reach of the “generally applicable” requirement in Section 4(a)(2) would be enormous. Under this interpretation Section 4(a)(2) would have the perverse effect of forcing States to require nondelegation in contexts where such a policy is irrational, counterproductive, or even dangerous as a condition of restricting abortion procedures to only licensed physicians. As a practical matter this application of S. 1696 would likely increase the number of women undergoing abortion-related procedures performed by nonphysicians.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that impedes access to abortion based on “one or more” factors described in Section 4(b)(3). The Section 4(b)(3) factors include Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.” The term “abortion provider” is defined by Section 3(2) as “a health care professional who performs abortions.” The term “health care professional,” in turn, is defined by Section 3(4) as “a licensed medical professional (including physicians, certified nurse-midwives, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) who is competent to perform abortions based on clinic training.” By definition laws that restrict the performance of abortion to licensed physicians would “interfere” with the ability of the nonphysicians described in Section 3(4) to perform abortions. If courts conclude that a prohibition on performing abortions interferes with the ability of those nonphysicians “to provide care and render services” “in accordance with” their “good-faith” medical judgment, as set forth in Section 4(b)(3)(A), then States would be forced to establish, by “clear and convincing” evidence, that laws restricting the performance of abortion to licensed physicians “significantly advance” either the safety of abortion services or the health of women and do so in the least restrictive way possible.

Health and safety regulations restricting the performance of abortion to licensed physicians would also suffer jeopardy under Section 4(b)(3)(B), Section 4(b)(3)(C), and Section 4(b)(3)(E).

S. 1696 Would Authorize Federal Court Attacks on Abortion Clinic Health and Safety Standards that Protect Women

The trial of abortionist Kermit Gosnell raised public awareness about the health and safety hazards threatening women at too many abortion clinics. The Susan B. Anthony List has compiled a list of reported allegations or established findings that includes items such as clinics with drugs decades past their expiration dates, mishandling of fetal tissue, a broken defibrillator, preparing to use unsterilized instruments on patients, patients that were regularly lying down in corridors and sometimes vomiting, a doctor conducting examinations with unwashed hands, blood-stained medical equipment, failure to disinfect recovery cots between each patient use, improper sedation and failure to resuscitate a patient who went into cardiac arrest, improper use of syringes, failure to test staff for rubella and TB, leaving the head of an aborted baby inside a mother’s womb, dead insects inside the facility, a mother who died as a result of hemorrhage following a surgical abortion, holes in a leaky ceiling, blood dripping from a sink p-trap in a room used by patients, the remains of aborted children being discarded in dumpsters, no oxygen available for patients, no emergency call system, insufficient or nonexistent narcotic logs, noncompliance with requirements regarding maintenance of sterile environments and sterile pre-operation handwashing, one doctor scrubbing his hands in a sink used for processing fetal remains, failure to provide local anesthesia causing patient experience of extreme pain, patients who tried to stop the abortion procedure and were restrained or subjected to the procedure anyway, failure to provide adequate protection for privacy, fraudulent billing practices, a situation where paramedics had to hand-lift a patient from a narrow doorway and down several steps because the clinic lacked a gurney-accessible entrance, failure to diagnose a tubal pregnancy, needles on the floor, and failure to clean exam tables between abortions.[21]The compiled list includes instances of women suffering complications from abortion or even dying.[22]

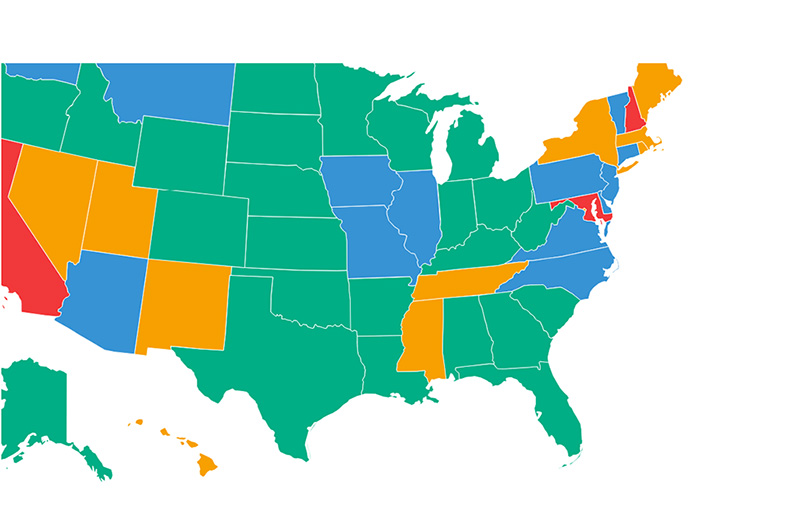

According to Americans United for Life (AUL), in 2013 “[a]t least 17 States considered measures mandating various health and safety standards for abortion clinics” and “[n]ew laws were enacted in Alabama, Indiana, North Carolina, North Dakota, and Texas.”[23] AUL reports that “Alabama and Texas now require abortion clinics to meet the same patient care standards as facilities performing other outpatient surgeries.”[24] Similarly, in 2013 “at least 15 States considered legislation delineating qualifications for individual abortion providers.”[25] According to AUL, “Alabama, North Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin enacted measures requiring abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a local hospital, while Louisiana and North Dakota now require that abortion providers be board certified in obstetrics and gynecology.”[26]

S. 1696 would threaten State laws regulating the health and safety of abortion clinics and the qualifications of abortion doctors. Section 4(a)(5) makes unlawful “[a] requirement or limitation concerning the physical plant, equipment, staffing, or hospital transfer arrangements of facilities where abortions are performed, or the credentials or hospital privileges or status of personnel at such facilities, that is not imposed on facilities or the personnel of facilities where medically comparable procedures are performed.” In some cases, state laws regulating the health and safety of abortion clinics might simply have the effect of raising standards for the practice of abortion to the same standards imposed and observed by other facilities.[27] In these cases, state officials might be able to defend health and safety measures as lawful under S. 1696. However, the process would be expensive, and success would not be guaranteed. S. 1696 fails to define the term “medically comparable procedures” and it is uncertain how courts would interpret that provision. Well-reasoned, carefully-tailored health and safety regulations could be struck down because they fail to satisfy the Section 4(a)(5) condition as applied by a single unelected federal judge. Even in cases where the State eventually prevailed, a federal judge might temporarily enjoin the health and safety regulations pending litigation. At a minimum, S. 1696 would create a statutory basis for entangling state health and safety regulations in federal court litigation.

In addition, even if States prevailed under Section 4(a)(5) by demonstrating that regulations governing the health and safety standards of abortion clinics and abortion doctors were the same as regulations governing the facilities or personnel of facilities where “medically comparable procedures” are performed, those regulations would still be subject to challenge under Section 4(b), which imposes a heightened burden of proof on certain measures and actions.

Section 4(b)(2)(A) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “singles out” the provision of abortion services or the facilities where abortion services are performed. S. 1696 fails to define the term “singles out” but commands courts to “liberally construe” provisions of S. 1696. If a court construed the term “singles out” to encompass any legislation or regulation specifically addressing abortion, even where such legislation or regulation merely raised abortion-related health and safety standards to the same standards applied in other contexts, then health and safety regulations designed to protect women could fall unless the State established by “clear and convincing” evidence that the regulations “significantly” advanced either the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible.

Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that impedes access to abortion based on “one or more” factors described in Section 4(b)(3). Those factors include Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.” Some abortion doctors might argue that regulations requiring them to become board certified in obstetrics and gynecology or to qualify for admitting privileges at a local hospital “interfere” with their ability to provide abortion services “in accordance with” their “good-faith” medical judgment. Upon such a showing States would be forced to satisfy the heightened burden of proof imposed by S. 1696 or those health and safety regulations would fall.

The Section 4(b)(3) factors also include Section 4(b)(3)(C), whether the measure or action is “reasonably likely” to “directly or indirectly” increase the cost of providing abortion services and Section 4(b)(3)(E), whether the measure or action is “reasonably likely” to result in a “decrease in the availability” of abortion services in the state. Providing safe, clean, hygienic abortion facilities with doctors who can obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals and obtain board certification in obstetrics and gynecology probably costs more money than providing inadequate, unhygienic, and dangerous abortion facilities with underqualified doctors. It is almost certain that complying with health and safety regulations will “directly or indirectly” increase the cost of providing abortion services. And if some abortion providers stop providing abortion services because they lack the ability or choose not to obtain admitting privileges or board certifications or to comply with other health and safety regulations then those regulations would also likely trigger the provision regarding a “decrease in availability” of abortion services. Under either showing, S. 1696 would jeopardize State regulations providing for the health and safety of women unless the State managed to satisfy the stiff burden of proof imposed by S. 1696.

S. 1696 Could Have the Effect of Deterring Health and Safety Inspections of Abortion Clinics

Inspections of abortion clinics are a vital tool for enforcing health and safety standards designed to protect women who choose to undergo abortion. However, S. 1696 could have the effect of deterring inspections of abortion clinics.

Section 4(b) of S. 1696 imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “singles out” abortion services or facilities. S. 1696 fails to define the term “singles out.” If a court concluded that a law authorizing inspections of abortion clinics or a particular safety inspection “singled out” abortion services or facilities, then the State would be forced to establish, by clear and convincing evidence, that the inspection law “significantly” advanced the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible.

In the end State officials might persuade a court that a law authorizing health and safety inspections of abortion clinics is valid under S. 1696. Even if a court concluded that a law authorizing inspections of abortion clinics “singled out” the provision of abortion services or the facilities where abortions are provided, State officials might establish through clear and convincing evidence that inspection laws significantly advance the safety of abortion services or the health of women and do so in the least restrictive way possible.

However, even where the State was able to sustain a law authorizing inspections of abortion clinics, the mere threat of litigation could deter State officials from putting the inspection law into practice. Section 4(b) applies to “measures” and “actions.” S. 1696 fails to define either of those terms, but courts could interpret either “measures” or “actions” to include inspections of abortion facilities, not just the laws that authorize those inspections.

If challenged to defend a practice of inspection in Federal court, State officials would likely offer the same arguments in defense of a particular inspection or plan of inspection that it offers in support of a law authorizing those inspections. However, litigation is costly, distracting, and time consuming. Even where government officials have carefully studied applicable standards and received legal counsel about appropriate actions, there is no guarantee a court will reach a favorable outcome. Further, S. 1696 would force State governments to pay the costs of litigation, including reasonable attorney and expert witness fees, to Planned Parenthood or other plaintiffs that prevail or even only “substantially” prevail in a challenge brought under S. 1696. The combination of these factors could produce a deterrent effect that leads to fewer safety inspections of abortion clinics.

More, in jurisdictions with fewer financial resources, the marginal increase in potential cost of defending abortion clinic inspections under S. 1696 might produce an even greater deterrent effect than in jurisdictions with greater financial resources. If so, then any effect of S. 1696 making abortion clinics more dangerous could fall disproportionately on women who seek access to abortion in jurisdictions with fewer financial resources yet nevertheless continue to depend on the protection of the law for enforcing at least minimum standards of safety and care.

S. 1696 Would Jeopardize Limits on Late Abortions

The Supreme Court of the United States has declared that after viability a State may proscribe abortion “except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”[28]This rule is often referred to as the “health exception.”

The scope of the health exception required by the U.S. Supreme Court has been subject to debate. If the term “health” is construed broadly, for example, to include any psychological, social, or emotional impact whatsoever, the exception has the effect of making abortion available throughout all of pregnancy without meaningful restriction.

Some States have crafted health exceptions that include physical but not psychological health and other States might not specify whether health exceptions to post-viability abortion restrictions include mental health.[29] Further, some States require “that a second physician certify that the abortion is medically necessary in all or some circumstances.”[30]

S. 1696 would jeopardize the ability of States to establish meaningful health exceptions to restrictions on late abortion.

Section 4(c)(2) of S. 1696 makes unlawful “[a] prohibition on abortion after fetal viability when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating physician, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant woman’s life or health.” S. 1696 fails to define the term “health” but instructs courts to “liberally construe” provisions of S. 1696. Some courts might liberally construe the term “health” to encompass psychological health and even other factors such as socio-economic circumstances. Alternatively, courts might conclude that, instead of defining the scope of the health exception set forth in Section 4(c)(2), Congress reserved that determination to the “good-faith medical judgment” of the treating physician. In practice, and because S. 1696 does not define the term “good-faith medical judgment,” this interpretation of Section 4(c)(2) could produce substantially the same effect as expansively construing the term “health” to include psychological and even other factors.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes heightened scrutiny on measures that impede access to abortion based on one or more factors described in Section 4(b)(3). Section 4(b)(3) factors include Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.” Abortion providers could argue that a health exception that does not provide for consideration of psychological, economic, social or other factors “interferes” with their ability to “provide care and render services” in “accordance” with their “good-faith medical judgment.” If a court agreed, then a State would be forced to establish by clear and convincing evidence that its health exception “significantly” advanced the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible. Late abortion can be dangerous to women, but health and safety are not the only legitimate goals of abortion regulation. For example, “the government has a legitimate, substantial interest in preserving and promoting fetal life.”[31] To the extent that carefully tailored post-viability health exceptions are designed to advance the government’s “substantial interest” in preserving and promoting the life of unborn children, it is reasonable to expect that at least some courts would conclude that the policy does not satisfy the required burden of proof.

In addition, S. 1696 would almost certainly wipe out regulations requiring the involvement of a second physician in post-viability abortions. Section 4(c)(2) makes unlawful “[a] prohibition on abortion after fetal viability when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating physician, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant woman’s life or health” (emphasis added). Even if courts construed “health” narrowly to coincide with the most stringent definition of “medical necessity” provided by the law of a State, Section 4(c)(2) restricts such judgments to “the” treating physician. The use of the definite article “the” in Section 4(c)(2) would likely result in the invalidation of regulations requiring the involvement of a second physician in late abortions. Furthermore, Section 4(a)(6) makes unlawful “[a] requirement that, prior to obtaining an abortion, a woman make one or more medically unnecessary visits to the provider of abortion services or to any individual or entity that does not provide abortion services.” S. 1696 does not define the term “medically unnecessary.” If the regulation requiring involvement of a second physician resulted in an extra visit to “any individual or entity” and those visits were adjudged to be “medically unnecessary,” then the second physician requirement likely would be struck down.

If S. 1696 were construed to require an expansive health exception or invalidate regulations requiring involvement of a second physician in late abortions, then S. 1696 would effectively freeze further litigation regarding the constitutional standards that apply to those issues. As a general rule, federal courts “will not pass upon a constitutional question . . . if there is also present some other ground upon which the case may be disposed of. . . . Thus, if a case can be decided on either of two grounds, one involving a constitutional question, the other a question of statutory construction or general law, the Court will decide only the latter.”[32]

S. 1696 Would Jeopardize Prohibitions on Taxpayer-Funded Abortion—Including the Hyde Amendment—as well as Abortion Training

U.S. Supreme Court precedents establish that governments “need not commit any resources to facilitating abortions.”[33] However, S. 1696 would jeopardize the ability of both the State and Federal government to prohibit the use of taxpayer funds for the purpose of performing abortions and training in abortion procedures.

Taxpayer-Funded Abortion

Section 4(d) states that S. 1696 does not apply to “insurance coverage of abortion.” Therefore, State and Federal prohibitions on taxpayer funds for elective abortions in the context of insurance coverage would survive the application of S. 1696. However, S. 1696 would continue to apply to prohibitions not subject to the “insurance coverage” exclusion.

Federal law provides several examples of prohibitions, or purported prohibitions, on elective abortion in taxpayer-funded programs. In each case the prohibition would be subject to jeopardy under S. 1696, as set forth below, so long as courts ruled the prohibition did not fall within the meaning of “insurance coverage” as that term is used in Section 4(d).

The Hyde Amendment and Medicaid. The “Hyde Amendment” is a federal policy that prohibits certain federal funds, including funds appropriated for the Medicaid program, to be used for elective abortion.[34] “In the years before the Hyde Amendment was first enacted by Congress in 1976, Medicaid was required to pay for about 300,000 abortions a year.”[35] Under the Hyde Amendment Medicaid funds may no longer be used for elective abortion.

As explained above, Section 4(d) states that S. 1696 does not apply to “insurance coverage.” Therefore, a threshold question would be whether Medicaid funds subject to the Hyde Amendment fall within the meaning of the term “insurance coverage” as that term is used in S. 1696. Plaintiffs seeking to challenge the Hyde Amendment restriction on Medicaid funds might argue, for example, that because Medicaid is a public entitlement program it is not “insurance coverage.” Plaintiffs might also argue, more fundamentally, that Congress knows how to draft abortion rights legislation that unambiguously protects restrictions on taxpayer funded abortion and chose not to do so here. In 1993, U.S. Senate Bill 25, the Freedom of Choice Act of 1993, was reported to the Senate with language stating that “[n]othing in this Act shall be construed to . . . prevent a State from declining to pay for the performance of abortions . . . .”[36] Plaintiffs could argue that the omission of similarly unambiguous language in S. 1696 supports the understanding that S. 1696 does not and was not intended to exclude Medicaid funds subject to the Hyde Amendment from application of S. 1696.

Given the ambiguity of S. 1696 as currently drafted, it is impossible to predict how courts confronted with challenges to Hyde Amendment restrictions on Medicaid funds would interpret the term “insurance coverage.” Federal courts sometimes interpret statutory terms in unpredictable and counterintuitive ways. See, e.g., National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 132 S. Ct. 2566, 2596 (2012) (concluding that “what is called a ‘penalty’ here may be viewed as a tax”). Analysis of S. 1696 in its current form should be based on the possibility that courts would conclude that the Hyde Amendment restrictions on Medicaid funds fall outside the meaning of the term “insurance coverage” as used in S. 1696 and therefore within the scope of any applicable prohibitions imposed by S. 1696. The same approach applies to taxpayer funds subject to the three prohibitions described in the following paragraphs.

The Hyde Amendment, Executive Order 13535, and PPACA-Funded CHC Programs. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) creates a Community Health Centers Fund and makes appropriations for the support of Community Health Centers (CHCs).[37] One question is whether CHCs may, or even must, provide abortion services in programs receiving PPACA funds.

On March 24, 2010, one day after he signed the PPACA, President Obama issued Executive Order 13535.[38] In the Executive Order President Obama stated that the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits abortion in certain federally funded programs, would apply to CHC programs receiving PPACA funds. “Under [PPACA], the Hyde language shall apply to the authorization and appropriations of funds for Community Health Centers under section 10503 [of PPACA] and all other relevant provisions. I hereby direct the Secretary of HHS to ensure that program administrators and recipients of Federal funds are aware of and comply with the limitations on abortion services imposed on CHCs by existing law.”[39]

Debate ensued about whether Executive Order 13535 effectively prohibited abortion in PPACA-funded CHC programs. One analysis, for example, argued that the Hyde Amendment does not apply to PPACA-funded CHC programs, PPACA does not independently prohibit CHCs from providing abortions in PPACA-funded programs, absent a statutory restriction courts are likely to interpret PPACA to require abortion in PPACA-funded CHC programs, and the President of the United States lacks the constitutional authority independently to prohibit abortion services where courts rule that abortion services are required by PPACA in PPACA-funded CHC programs.[40]

If the Hyde Amendment or Executive Order 13535 or both sources of law prohibit abortion services in PPACA-funded CHC programs, then that prohibition would be subject to jeopardy under S. 1696, as set forth below.

Title X Family Planning Programs. Title X of the Public Health Services Act “provides federal funds for project grants to public and private nonprofit organizations for the provision of family planning information and services.”[41]Organizations receiving Title X funds include Planned Parenthood.[42] Federal law currently prohibits Title X funds from being used in programs where abortion is a method of family planning.[43]

The Mexico City Policy. The Mexico City Policy was first instituted by President Reagan in 1984. The policy “required nongovernmental organizations to agree as a condition of their receipt of Federal funds that such organizations would neither perform nor actively promote abortion as a method of family planning in other nations.”[44] Following the Reagan Administration, President George H.W. Bush continued the policy, President Clinton rescinded the policy, President George W. Bush reinstated the policy, and President Obama rescinded the policy.[45] The question is whether S. 1696 would jeopardize the ability of a future president to reinstate the policy.

In several ways S. 1696 would jeopardize not only these and any other Federal policies but also similar State policies that prohibit taxpayer funds from being used to support abortion outside the context of “insurance coverage.”

Section 4(c)(1) makes unlawful “[a] prohibition or ban on abortion prior to fetal viability.” On its face Section 4(c)(1) appears to address measures that would make unlawful the performance of abortion prior to fetal viability. Prohibitions on taxpayer-funded abortion do not make abortion unlawful, they merely restrict abortion in programs receiving taxpayer funds. However, Section 5 commands courts to “liberally construe” provisions of S. 1696 to “effectuate” its purposes. Some courts might conclude that prohibitions on abortion in taxpayer-funded programs constitute a “prohibition” within the meaning of that term as used in Section 4(c)(1). Under this interpretation, prohibitions on elective abortions in taxpayer-funded programs would be invalid when applied before viability, which is when most abortions take place.

Section 4(a)(3) makes unlawful “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to prescribe or dispense drugs based on her or his good-faith medical judgment, other than a limitation generally applicable to the medical profession.” Providers subject to restrictions attached to taxpayer funds might argue that those restrictions create a “limitation” on their ability to prescribe or dispense drugs that does not apply generally to other health care professionals. S. 1696 does not define the term “limitation” but S. 1696 commands courts to “liberally construe” provisions of S. 1696 to effectuate its purposes. Similarly, organizations that wish to have their employees provide abortions in programs covered by restrictions attached to taxpayer funds, or individuals seeking services in those programs, might argue that they are “aggrieved” by the alleged violation of Section 4(a)(3). Section 6(b)(1) of S. 1696 creates a private right of action for any individual or entity aggrieved by an alleged violation of S. 1696.

Section 4(b) would provide additional bases for challenging prohibitions on taxpayer funding for abortion. Section 4(b) imposes a heightened burden of proof on certain measures or actions.

Section 4(b)(2)(A) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “singles out” the provision of abortion services. If a court concludes that the restrictions on abortion attached to taxpayer funds “single out” the provision of abortion services, then those policies could be enforced only by establishing, through “clear and convincing evidence,” that they “significantly” advance the safety of abortion services or the health of women in the least restrictive way possible.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that impedes access to abortion based on “one or more” of the seven factors described in Section 4(b)(3). Those factors include Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment.” Abortion providers subject to restrictions attached to taxpayer funds could argue that those policies “interfere” with their ability to “provide care” and “render services” in “accordance” with their “good-faith” medical judgment. Similarly, organizations that wish to have their employees provide abortions in programs covered by restrictions attached to taxpayer funds, or individuals seeking services in those programs, might argue that they are “aggrieved” by the alleged violation of Section 4(b). Section 6(b)(1) of S. 1696 creates a private right of action for any individual or entity aggrieved by an alleged violation of S. 1696.

The Section 4(b)(3) factors also include Section 4(b)(3)(C), “[w]hether the measure or action is reasonably likely to directly or indirectly increase . . . the cost for obtaining abortion services.” Abortion providers subject to restrictions attached to taxpayer funds, or individuals seeking services in those programs, might argue that not providing abortion in programs covered by those policies would “indirectly” increase the cost for obtaining abortions by reducing the availability of abortion in general or the availability of free or subsidized abortion in particular. Section 6(b)(1) creates a private right of action for any individual or entity aggrieved by an alleged violation of S. 1696 and Section 6(b)(2) expressly authorizes medical professionals to commence an action on behalf of the professional’s patients who might be adversely affected by an alleged violation of S. 1696.

Prohibitions on taxpayer-funded abortion subjected to the heightened burden of proof under either provision of Section 4(b) would fall unless the government established by clear and convincing evidence that those policies “significantly advanced” either the safety of abortion services or the health of women and did so in the least restrictive way possible. Abortion can be dangerous to mothers, but health and safety are not the only legitimate goals of abortion regulation. For example, “the government has a legitimate, substantial interest in preserving and promoting fetal life,”[46] the government is “permitted to enact persuasive measures which favor childbirth over abortion, even if those measures do not further a health interest,”[47] and “the government may ‘make a value judgment favoring childbirth over abortion, and . . . implement that judgment by the allocation of public funds.’”[48]To the extent that prohibitions on taxpayer funded abortion are designed to advance a policy choice “favor[ing] childbirth over abortion” rather than a health interest, it is reasonable to expect that courts would conclude that the policy does not satisfy the one-sided burden of proof imposed by S. 1696.

Taxpayer-Funded Abortion Training

S. 1696 would also jeopardize prohibitions on using taxpayer funds for abortion training.[49] Section 4(a)(7) makes unlawful “[a] requirement or limitation that prohibits or restricts medical training for abortion procedures, other than a requirement or limitation generally applicable to medical training for medically comparable procedures.” Section 5 commands courts to “liberally construe” the provisions of S. 1696. Applying Section 5, courts might conclude that a policy prohibiting taxpayer funds for abortion training is a “requirement” or “limitation” within the meaning of Section 4(a)(7) and that such a policy “restricts” medical training for abortion procedures. In this reading, State governments would not be permitted to prohibit taxpayer funds from being used for abortion training unless they also prohibited taxpayer funds from being used for training in “medically comparable procedures.” Because S. 1696 fails to define the term “medically comparable procedures” and commands courts to “liberally construe” the provisions of S. 1696, courts could give the term “medically comparable procedures” such a broad construction that, as a practical matter, no State would choose to attempt to satisfy the “generally applicable” standard required to prohibit taxpayer funding for abortion training.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(A) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “singles out” the “provision of abortion services.” Section 5 commands courts to “liberally construe” S. 1696. Applying Section 5, a court might construe the phrase “provision of abortion services” to include the training required to provide such services. Under this interpretation a restriction on using taxpayer funds for abortion training would likely be considered a measure that “singles out” the provision of abortion services and is therefore subject to a heightened burden of proof. In this outcome such a policy would stand only if the State established by “clear and convincing evidence” that its policy “significantly” advanced the safety of abortion services or the health of women and that the measure or action was the least restrictive means of doing so.

Abortion can be dangerous to mothers, but health and safety are not the only legitimate goals of abortion regulation. For example, “the government has a legitimate, substantial interest in preserving and promoting fetal life,”[50] the government is “permitted to enact persuasive measures which favor childbirth over abortion, even if those measures do not further a health interest,”[51] and “the government may ‘make a value judgment favoring childbirth over abortion, and . . . implement that judgment by the allocation of public funds.’”[52] However, to the extent prohibitions on using taxpayer funds for abortion training are designed to advance the government’s interest in “promoting fetal life” or policies that “favor childbirth over abortion” rather than a health interest, it is reasonable to expect that at least some courts would conclude that prohibitions on taxpayer funding for abortion training do not satisfy the one-sided burden of proof imposed by S. 1696.

S. 1696 Would Jeopardize Health and Safety Regulations Governing the Use of Abortion Drugs

Medication abortion is distinct from surgical abortion. Surgical abortion involves removing the child from the womb through suctioning or with instruments such as forceps.[53] Medication abortion involves the mother ingesting drugs that disrupt the pregnancy and cause the unborn child to be expelled from the womb.

For medication abortion the Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of the drug known as Mifeprex (mifepristone).[54] Mifeprex is administered in conjunction with a drug known as misoprostol and, as set forth in the label approved for Mifeprex, involves three steps. First, the mother receives a dose of Mifeprex (mifepristone).[55]Second, the mother receives a dose of misoprostol.[56] Third, the woman “must “return” to the provider about 14 days after she has taken Mifeprex to be sure she is well and that the life of the unborn child has been successfully terminated.[57] These drugs are sometimes referred to as the Mifeprex regime, the RU-486 regime, or just RU-486.

The FDA approved Mifeprex under a regulation providing for “restrictions to assure safe use”[58] and the labeling approved for Mifeprex includes extensive health and safety guidelines. For example, Mifeprex is “not approved” for “ending later pregnancies.”[59] Women should “not take” Mifeprex if “[i]t has been more than 49 days (7 weeks) since your last menstrual period began.”[60] In addition, the labeling approved for Mifeprex expressly contemplates that women will undergo each of the three steps in the Mifeprex regime—including the dosage of misoprostol administered in the second step— “at your provider’s office.”[61]

Furthermore, as set forth in a document available on the FDA website, the FDA determined that a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) “is necessary” for Mifeprex to ensure that the “benefits” of the drug outweigh the “risks of serious complications.”[62] As set forth in the REMS abortion providers wishing to provide Mifeprex must first sign a Prescriber’s Agreement stating they satisfy certain qualifications and will follow certain guidelines.[63]The Prescriber’s Agreement expressly states that, “[u]nder Federal law,” Mifeprex “must be” provided by or under the supervision of a physician who meets certain qualifications including the “[a]bility to provide surgical intervention in cases of incomplete abortion or severe bleeding, or have made plans to provide such care through others, and are able to assure patient access to medical facilities equipped to provide blood transfusions and resuscitation, if necessary.”[64] The Prescriber’s Agreement also informs providers that they “must” provide Mifeprex “in a manner consistent with” guidelines that include the statement that “[t]he patient’s follow-up visit at approximately 14 days is very important to confirm that a complete termination of pregnancy has occurred and that there have been no complications.”[65]

In addition to health and safety guidelines required or approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, many States have adopted health and safety regulations that govern the performance of medication abortion.[66] Texas, for example, recently enacted health and safety regulations that, subject to a specified exception, require that the administration of the abortion-inducing drug “satisfies the protocol tested and authorized by the United States Food and Drug Administration as outlined in the final printed label of the abortion-inducing drug.”[67] The Texas health and safety regulations also require that the person who administers the abortion-inducing drugs be a physician,[68]that before the physician administers the abortion-inducing drug the physician examine the pregnant woman and document the gestational age and intrauterine location of the pregnancy,[69] and that the physician or physician’s agent schedule a follow-up visit for the woman to occur not more than 14 days after the administration of the abortion-inducing drug and during this visit confirm that the pregnancy is completely terminated and assess the degree of bleeding.[70] Other States, while not specifically requiring conformance to FDA-approved guidelines, restrict performance of abortion to licensed physicians or require the physician prescribing abortion medication to be in the presence of the patient.[71]

Documents available on the FDA website set out the potential adverse events associated with Mifeprex. In 2000 the FDA approved labeling for Mifeprex that stated that adverse events following the administration of Mifeprex and misoprostol in trials included abdominal pain, uterine cramping, nausea, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, fatigue, back pain, uterine hemorrhage, fever, viral infections, vaginitis, rigors (chills/shaking), dyspepsia, insomnia, asthenia, leg pain, anxiety, anemia, leucorrhea, sinusitis, syncope, endometritis/salpingitis/pelvic inflammatory disease, decrease in hemoglobin greater than two g/dL, pelvic pain, and fainting.[72] In 2005 the FDA approved labeling for Mifeprex that stated that adverse reactions reported during the post-approval use of Mifeprex and misoprostol include allergic reaction (including rash, hives, itching), hypotension (including orthostatic), lightheadedness, loss of consciousness, post-abortal infection (including endomyometritis, parametritis), ruptured ectopic pregnancy, shortness of breath, and tachycardia (including racing pulse, heart palpitations, heart pounding).[73] In 2009 the FDA approved labeling for Mifeprex that stated that “[n]early all of the women who receive Mifeprex and misoprostol will report adverse reactions, and many can be expected to report more than one such reaction.”[74]In 2011 the FDA reported that post-marketing reports of adverse events that occurred among patients who had taken mifepristone for abortion included 14 deaths, 39 instances of blood loss requiring transfusion, and 256 instances of infection including 48 instances of severe infection.[75]

Threats to State Regulations

S. 1696 would jeopardize the ability of States to impose health and safety regulations governing the use of abortion-inducing drugs. Section 4(a)(3) of S. 1696, for example, makes unlawful “[a] limitation on an abortion provider’s ability to prescribe or dispense drugs based on her or his good-faith medical judgment, other than a limitation generally applicable to the medical profession.” S. 1696 fails to explain what kind of limitation on the ability to prescribe or dispense drugs that applied to the Mifeprex regime would also qualify as generally applicable to the medical profession. One potential interpretation of Section 4(a)(3) would be that only an across-the-board ban on off-label uses of all FDA-approved drugs would both restrict off-label uses of the Mifeprex regime and qualify as generally applicable to the medical profession. Under this interpretation States would face a perverse dilemma. States would be forced either to permit abortion providers to subject women to potentially dangerous off-label uses of the Mifeprex regime or to ban all off-label uses of all FDA-approved drugs even though in many cases prescribing FDA-approved drugs for off-label uses might significantly promote patient health. Faced with this choice it seems unlikely that many, if any, States would impose regulations that advance the health and safety of women by requiring administration of the Mifeprex regime according to FDA-approved guidelines.

Other provisions of S. 1696 would also threaten the ability of States to regulate the use of abortion-inducing drugs for health and safety. Section 4(a)(1), for example, makes unlawful “[a] requirement that a medical professional perform specific tests or follow specific medical procedures in connection with the provision of an abortion, unless generally required for the provision of medically comparable procedures.” S. 1696 fails to define what procedures would be “medically comparable” to the Mifeprex regime. If a court ruled that any procedure involving a patient consuming prescription drugs was “medically comparable” to the Mifeprex regime then the State would be prohibited from requiring abortion providers to determine the gestational age of the unborn child, determine whether a pregnancy was ectopic, test for continued pregnancy, and schedule follow-up tests unless those same tests or procedures were required in every situation involving a patient consuming prescription drugs. Faced with this dilemma it seems unlikely that many, if any, States would impose regulations providing for women’s health and safety in the administration of abortion-inducing drugs.

Other provisions of S. 1696 that would jeopardize those regulations include Section 4(b)(2)(A) and Section 4(b)(2)(B). Both these provisions impose a heightened burden of proof on certain measures and actions.

Section 4(b)(2)(A) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “singles out” the provision of abortion services. As with several other key terms, S. 1696 fails to define the term “singles out.” If courts conclude that health and safety regulations governing the use of abortion-inducing drugs “single out” abortion then States would be required to establish, by clear and convincing evidence, that those regulations significantly advance either the safety of abortion services or the health of women and do so in the least restrictive way possible.

In addition, Section 4(b)(2)(B) imposes a heightened burden of proof on any measure or action that “impedes women’s access to abortion services based on one or more of the factors described in” Section 4(b)(3). Section 4(b)(3), in turn, describes several factors that could apply to prohibitions on potentially dangerous off-label uses of the Mifeprex regime, including Section 4(b)(3)(A), “[w]hether the measure or action interferes with an abortion provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with her or his good-faith medical judgment,” Section 4(b)(3)(C), “[w]hether the measure or action is reasonably likely to directly or indirectly increase the cost of providing abortion services or the cost for obtaining abortion services (including costs associated with travel, childcare, or time off work),” and Section 4(b)(3)(D), “[w]hether the measure or action requires, or is reasonably likely to have the effect of necessitating, a trip to the offices of the abortion provider that would not otherwise be required.” Between these three provisions S. 1696 would jeopardize regulations restricting the use of Mifeprex to cases of early pregnancy, restricting the performance of abortion to licensed physicians, requiring the prescribing physician to be in the presence of the patient, requiring women to take each step of the Mifeprex regime at the provider’s office, and requiring providers to schedule a follow-up visit at 14 days. For each regulation subjected to heightened scrutiny under S. 1696, States would be required to establish, by clear and convincing evidence, that the regulation significantly advances either the safety of abortion services or the health of women and does so in the least restrictive way possible.

Threats to Federal Regulations

In addition to threatening the ability of States to regulate procedures involving abortion-inducing drugs, S. 1696 could threaten the ability of the FDA to regulate abortion-inducing drugs. As described in Section 4(e), S. 1696 applies to “government restrictions on the provision of abortion services, whether statutory or otherwise, whether enacted or imposed prior to or after the date of enactment of the Act” (emphasis added), and Section 3(3) defines “government” to include a department or agency acting under color of law of the United States. The FDA approved Mifeprex under a regulation providing for “restrictions to assure safe use.”[76] Under this regulation, if the FDA concludes that a drug can be safely used “only if distribution or use is restricted,” then the FDA “will require” postmarketing restrictions such as “[d]istribution conditioned on the performance of specified medical procedures.”[77]

A review of the regulatory history of Mifeprex reveals that, in fact, the FDA determined that a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy [REMS] “is necessary” for Mifeprex to ensure that the “benefits” of the drug outweigh the “risks of serious complications.”[78] As set forth in the REMS, abortion providers wishing to provide Mifeprex must first sign a Prescriber’s Agreement stating they satisfy certain qualifications and will follow certain guidelines.[79] The Prescriber’s Agreement expressly states that, “[u]nder Federal law,” Mifeprex “must be” provided by or under the supervision of a physician who meets certain qualifications including the “[a]bility to provide surgical intervention in cases of incomplete abortion or severe bleeding, or have made plans to provide such care through others, and are able to assure patient access to medical facilities equipped to provide blood transfusions and resuscitation, if necessary.”[80] The Prescriber’s Agreement also informs prescribers that they “must” provide Mifeprex “in a manner consistent with” guidelines including the statement that “[t]he patient’s follow-up visit at approximately 14 days is very important to confirm that a complete termination of pregnancy has occurred and that there have been no complications.”[81]