Although newborns have difficulty making eye contact and appear to do little more than eat, sleep and expel waste, they are actually keen observers of the world around them. In fact, newborns are born ready to quickly learn.

Become A Defender of Life

Your donation helps us continue to provide world-class research in defense of life.

DONATECharlotte Lozier Institute

Phone: 202-223-8073

Fax: 571-312-0544

2776 S. Arlington Mill Dr.

#803

Arlington, VA 22206

Gifted Newborns: Infant Learning

Newborns innately look at faces to gather emotional and communicative information. For example, when given a choice between fearful and smiling faces, infants zero to four days old look longer at happy faces.1 They also prefer faces with open eyes and faces that are looking directly at them instead of looking away.2 In an interesting follow-up study, newborns from zero to five days old spent more time looking at photographs of women they had previously seen in a video, but only if that woman had been looking at the baby during the video, not if she had been looking away.3 These findings suggest that eye contact plays an important role in memory and for creating a secure attachment between caregivers and their children.

Newborns imitate adult facial expressions and gestures. In a famous study, babies 1 hour to 3 days old watched videos of a stranger making faces. In one video, the stranger stuck out his tongue. In another video, he opened his mouth. Newborns only saw one of these two videos. Surprisingly, in the 20 seconds following the video, babies were more likely to mimic the action that they saw in the video.4 Furthermore, two-day-old infants were more likely to raise their index fingers, or make the “peace sign” after their mothers did the same.5 Interestingly, the newborns learned these finger movements quickly and their gestures improved with practice.

Newborns also follow an adult’s gaze. By following an adult’s gaze, a baby may figure out what that adult pays attention to, what his intentions are, and what he may do next. This helps babies learn what adults find important. When infants two to five days old watched cartoons of faces either looking towards or away from a target in the corner of the picture, infants looked at the target faster if they had been cued by the cartoon face’s gaze.6 In other words, newborns look at what other faces look at. Studies in older babies, from 6 to 12 months, show that a baby’s ability to follow an adult’s gaze predicts language and social development.7

Newborn babies show empathy. In fact, one-day-old babies cry when they hear a tape of another baby crying, but only if that baby is younger than they are. They do not cry when they hear recordings of their own cries, or the cries of older babies.8 When researchers performed the same test in babies at ages 1, 3, 6, and 9 months, they found that older babies also cry when they hear the cries of those younger than themselves.9

Babies are also predisposed to learning language. For the first four months or so, a baby in an English-speaking home can distinguish between the sounds in other languages. However, by the time she is one year old, she has lost this ability. As language circuits in her frontal and temporal lobes gain efficiency, her brain becomes wired to hear the language she hears at home.10 Even more impressively, children instinctively learn to break speech sounds into meaningful units, like syllables and words, simply by listening to how likely certain speech sounds are to occur together.11 And when researchers studied deaf children in Nicaragua, who neither heard spoken Spanish, nor had seen any sign language, they found that the children created a gestured-language that had grammatical regularities, even though they had no linguistic input. This suggests that children have the innate ability not just to learn grammar, but to create language.12

Perhaps most surprisingly, infants process numerical information in the area of the brain where adults process math. Specifically, when researchers showed 3-month-old infants a long series of images with four objects, and then showed an image with eight objects, the number-processing brain network responded with extra brain activity that could be measured using an electroencephalogram or EEG.13 The number-processing brain circuit, or parietoprefrontal network, is the same brain circuit that 4-year-olds and adults use to process numbers. When the experiment was repeated using different numbers of objects, such as 2 vs. 3 and 12 vs. 4, the babies’ brains consistently showed activity in the parietoprefrontal cortex.14 Babies can also detect differences in the number of sounds or actions.15 However, there are limits. For example, six-month-old babies have difficulties telling the difference between two quantities if the ratio between them is less than 2:1. In other words, they can distinguish between 8 and 16 objects, but not 8 and 12 objects. Nine- and ten-month-old babies can make finer distinctions such as 8 vs. 12 objects, but not smaller ones, such as 8 vs. 10 objects.16 Taken together, babies have an approximate sense of number.

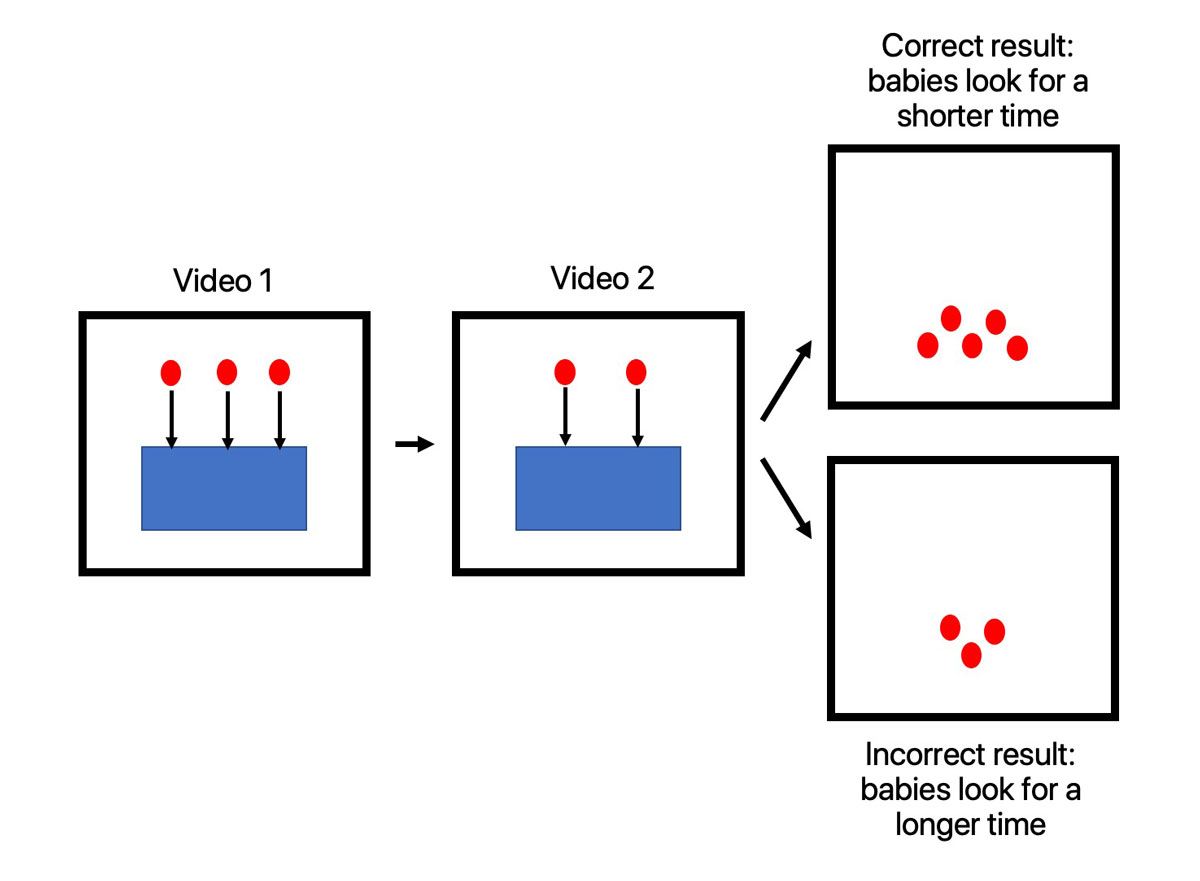

Even more impressively, babies appear to perform simple math.

Researchers found that babies can perform simple addition and subtraction by examining how long they looked at videos with correct and incorrect results. Specifically, researchers showed nine-month-old babies videos where sets of circles went and hid behind a bigger rectangle. In one video showing addition, three circles hid behind the rectangle, and then another two circles hid behind the rectangle. In another video showing subtraction, ten circles hid behind the rectangle and then five circles slid back out. Then the rectangle disappeared to reveal either three or five circles. In both scenarios, babies spent more time looking at the screen if it displayed the wrong number of circles. 17 Simply put, babies expected the correct answers. (Image Credit: Katrina Furth, Ph.D.)

Overall, as more and more research focuses on the abilities of the unborn and infants, scientists have come to realize that babies are more than just survival machines — they have remarkable capacities for learning about the world around them and responding to it.