Stem Cell Research: Predictions, Predilections and Progress

A recent blog posted on the science/technology website Gizmodo conducts an interesting thought experiment. The author goes back 10 years to the December, 2005, issue of Scientific American. In that issue was the “Scientific American 50” – a list of the 50 leading scientific trends for that year.

The author wanted to see what has happened, 10 years on, in realizing “the highly-touted breakthroughs of the era that would supposedly change everything.” The author writes that she chose 2005 “because 10 years seemed recent enough for continuity between scientific questions then and now but also long enough ago for actual progress. More importantly, I chose Scientific American because the magazine publishes sober assessments of science, often by scientists themselves.”

The author soon finds out that the predicted breakthroughs never happened or fell far short of the hyped-up promises. For example, in the area of solar energy cells, predictions foresaw solar panels that absorb infrared light; more efficient dye-based solar cells; and a hybrid solar cell that could generate and store electricity, among others. Ten years on, none of these has been fully realized and all are still works in progress.

The same is true for most of the other predictions. That a vaccine patch would be commonplace succumbed to series of failed clinical trials. A chemical cocktail that would help repair hearts by stimulating heart cells to divide is still a work in progress. Predictions regarding the creation of lab-synthesized cell membranes have still not been realized.

And on and on. The author concludes “… science can be wrong. It can go down dead ends. And even when it doesn’t, almost everything is more complicated and takes longer than we initially think.”

The lead item on the 2005 list of the most promising scientific trends is a good illustration of that conclusion: a prediction of “patient-specific stem cells that pave the way for stem cell therapy.” But, as the author notes, this prediction was based on “a stem cell breakthrough that turned out to be one of the biggest cases of scientific fraud ever.”

That would be the cloning fraud perpetrated, beginning in 2004, by Korean researcher Hwang Woo-suk. In March of that year Hwang announced, in the pages of the prestigious journal Science, that he had successfully created a human embryo by cloning and then extracted a viable embryonic stem cell line from that cloned embryo (which was destroyed in the process). Just over a year later, Hwang further announced (also in Science) that he had created 11 embryonic stem cell lines from embryos cloned using cells from different patients with different diseases.

The news caused an international sensation, with Hwang being lionized both in the media and by his peers in the scientific community; the South Korean government even issued a stamp commemorating his “breakthrough.”

To understand why Hwang’s claims to have successfully cloned human embryos created such a sensation, it is necessary to recall the backdrop against which it took place.

For years, leading researchers and public policy makers hyped human research cloning as an absolute necessity for the future of regenerative medicine. For regenerative medicine to be successful, stems cell genetically matched to patients would be necessary, and at the time it was believed such stem cells could only be created by human cloning. Hyping the potential of cloning for human research became a way to win public support and, just as important, public funding for it.

To take one example: in 2001, before a U.S. Senate committee, Michael West, a leading proponent of human cloning for research and then-head of Advanced Cell Technology, testified that “on the scientific front, I think it’s useful to point out that mankind occasionally is given gifts, things that can greatly advance the human condition. I think we’ve been given two in just recent history. The first, as we’ve talked about at some length already this morning, is the human embryonic stem cell. … A second gift we’ve been given is this miracle we call cloning, or nuclear transfer.[i]”

An analysis of British and U.S media coverage of the public policy debate over human cloning for research found similar patterns of hype. One British commentator cited in the study even compared the potential of human cloning to the miracles of Jesus, referring to “the near-miraculous ingenuity of this kind of science, with its almost miraculous benefits. Jesus was rather keen on miraculous healing himself.[ii]”

With hype of this magnitude, it is not implausible to surmise that the fame and adulation that would surely come with being the first to successfully clone a human embryo seduced Hwang into committing his fraud.

But leaving aside the particulars of the Hwang scandal, the 2005 prediction that patient- specific stem cells will pave the way for stem cell therapies is proving to be not so far off after all – but in ways completely unforeseen by those who a decade ago so confidently and disingenuously hyped human embryonic stem cell research (hESCR) and human cloning for research.

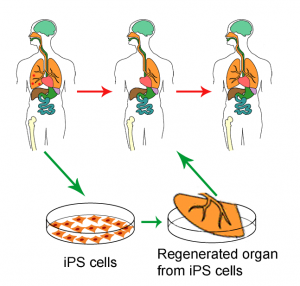

In 2007, Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka announced that he had developed a method to reprogram an ordinary somatic cell, such as a skin cell, into an embryonic-like pluripotent state. Yamanaka dubbed these cells “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPSCs) because the somatic cell is induced to become a pluripotent cell. These cells possess the same pluripotent characteristics of embryonic stem cells; however, they are neither obtained from the destruction of embryos, nor by using eggs or cloning. Yamanaka’s breakthrough earned him the Nobel Prize in medicine and quickly became the preferred method for producing patient-specific stem cells for research in regenerative medicine.

Indeed, Ian Wilmut, perhaps the man most closely associated with cloning for his work in creating Dolly the sheep, announced in 2007 that he was giving up on cloning to pursue research using iPSCs. And the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine – established by voter referendum in 2004 with the express mission of giving priority funding to hESCR and cloning for research – has not funded a research cloning program since 2010. Indeed, the bulk of CIRM’s funding now goes to projects primarily using adult, induced pluripotent and other non-embryonic stem cells (here and here).

Researchers did finally succeed, in 2011, and then again in 2013, in creating human embryos via the cloning process, but the development received a rather tepid response from the scientific community. While acknowledging the technical achievement involved in this development, most scientists shrugged off its therapeutic potential. For example, Dr.Rudolf Jaenisch, a vocal proponent of cloning for research, said that while “an outstanding issue of whether [cloning] would work in humans has been resolved,” it “has no clinical relevance.”

The decade-old prediction of patient-specific stem cells paving the way for stem cell therapies, then, was not wrong or even misplaced – only that it is ethically non-contentious patient-derived adult and induced pluripotent stem cells that are proving most promising in developing therapies.

The predictions from a decade ago that remain unfulfilled are those which so confidently saw in human cloning the future of regenerative medicine.

Gene Tarne is a Senior Analyst with the Charlotte Lozier Institute.

[i] Testimony of Michael West before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies, 8/1/01.

[ii] Minette Marrin, “Embryo Cell Research Is a Triumph not a Tragedy,” Sunday Times, March 3, 2002, Features sec., 8, cited in “Scientific Sensationalism in American and British Press Coverage of Therapeutic Cloning” pg.8, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, XX(X) 1–15.