Z.P.G. (Zero Population Growth) (1972)

“The penalty for birth…is death!” That’s the tagline and the premise of this U.S.-Danish dystopian drama – and, sadly, such a notion is not entirely foreign to today’s (not to mention 1972’s) population controllers.

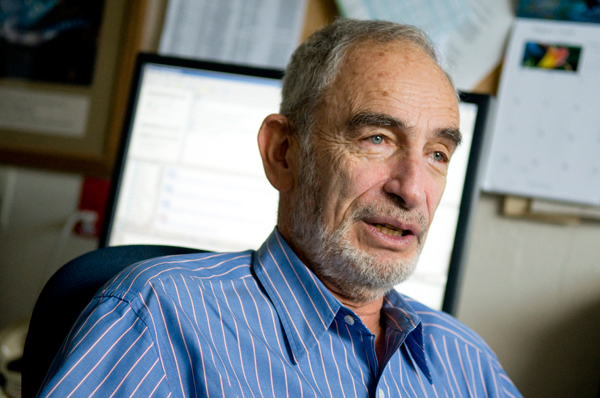

This sometimes eerily prophetic movie was made at the height of the late Sixties-early Seventies “overpopulation” hysteria prompted by entomologist Paul R. Ehrlich’s since thoroughly debunked, the-end-is-near fantasy, The Population Bomb (1968). Not one of insect expert Ehrlich’s ludicrous, sky-is-falling “predictions” came true; population growth has not outstripped the food supply and other resources, hundreds of millions of people – 65 million of them Americans – did not starve to death in the Seventies, India was not doomed, and England did not cease to exist by the year 2000. Ehrlich admits this today – what else could he do? – yet he insists it doesn’t prove he was fundamentally wrong.

Ehrlich favored imposing “compulsion if voluntary methods fail.” Four years later, Z.P.G. took such population control extremism and environmentalist frenzy to their logical conclusion: people would multiply so much they would wreck the entire environment, and a world government would then issue an edict that made having babies a capital offense.

Any clandestine babies spotted from then on would be executed along with Mom and Dad; people, all people, are the problem, after all. In Z.P.G.’s opening scene, an aircraft floating in the pea-soup-foggily polluted air broadcasts a no-more-babies-for-the-next-30-years edict to the subjects – for that is what they are – down below. Horrified, the crowds cry out, “No! No!” but fruitlessly. Told that “To conceive a child shall be the gravest of crimes, punishable by death,” they have no means of asserting their rights, of fighting back; gun control must have disarmed the populace at some point in the past.

https://youtu.be/zZZIDPgX4nE

Next, eight years in the future, people meekly wait in line to be given animatronic dolls the government is substituting for the toddlers they may not have. The dolls have a vaguely sinister appearance and say things like, “I love Mommy!” Looking disgusted, Carol McNeil (Geraldine Chaplin) exclaims, “Get me out of here!” and leaves the line, with her husband Russ (Oliver Reed) trailing.

Crowds go to a museum that portrays life as it was back in wasteful, benighted 1971, when the Earth’s flora and fauna still existed – they’re not around anymore – and when hoggish people ate all they wanted and owned polluting autos fueled by – gasp! – gasoline. The people in Z.P.G.’s auto-less world have no means of personal travel, and so no meaningful freedom of movement.

The museum has “Stay in Line” and “Obey the Rules” signs that obviously refer to much more than crowd control. The museum tells visitors about a “spatial crisis” so great that it entailed filling in lakes and ponds to make room for housing. And its “Gallery of Criminals” blames leaders of industry, politics and religion for harming the atmosphere by “irresponsibly” allowing the “devastating crime of overpopulation.” It illustrates the point with a brief film clip of Pope St. Paul VI, whose 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae (“On Human Life”) warned against the dangers of artificial contraception.

In the meantime, Carol pays a live screen “visit” to her physician, Dr. Mallory (Aubrey Woods). Hesitantly, she tells him, “I want a baby. My baby.” With a cruel, implacable look that personifies all the mercilessness of dictatorial, unfettered government, he warns her in menacing tones that her wish is impossible. In a close-up shot, a tear wells up and rolls down Carol’s cheek.

After eight babyless years, most people have become anti-life, and some even are informers who turn in any couples who have dared to have a child. A furious woman screams “Baby! Baby!” at a hapless couple and their little one, and a pitiless crowd holds the three of them for on-the-spot execution via suffocation under a dome lowered on them by a hovering aircraft. (We don’t see the suffocation.) For them no judge or jury, no trial or defense; their innocent baby is proof of their “guilt.”

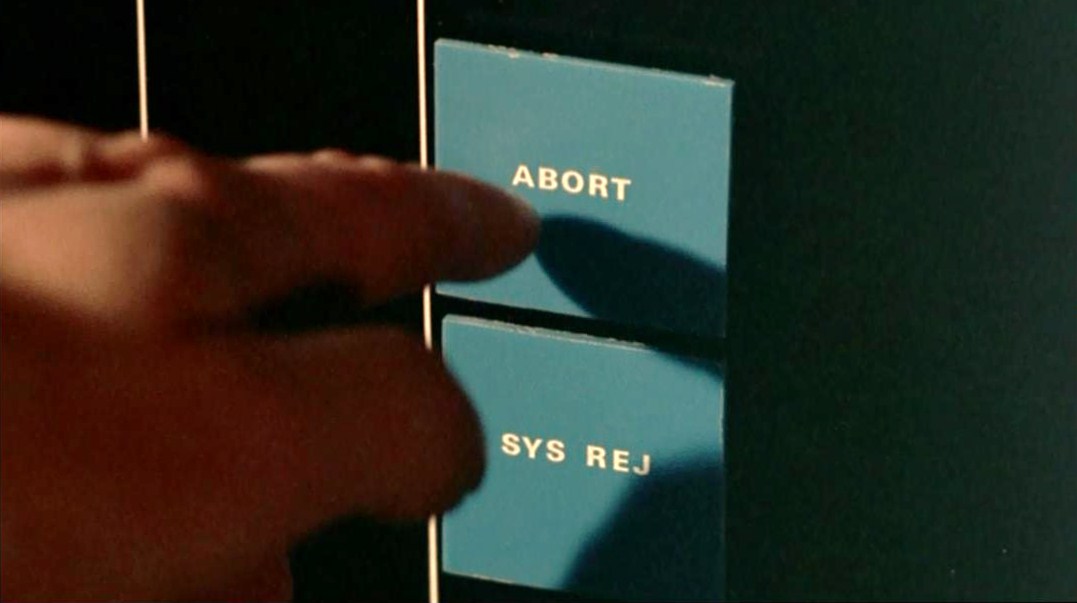

Carol becomes with child, and after some embracing in bed one night, Russ orders her to “go and take care of it.” Planned Parenthood would be envious; every domicile has a bathroom wall gizmo that at the push of a button kills a preborn child, apparently by shooting a death ray through a mother. In the bedroom, Russ hears the machine whirr and is satisfied. SPOILER ALERT: Little does he know.

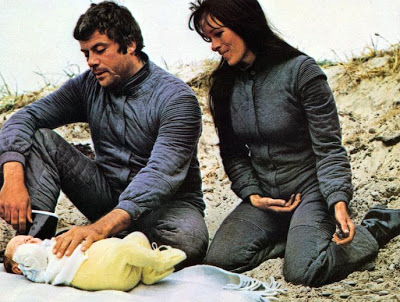

At Christmastime, Carol reveals to Russ that she didn’t kill their baby, who is now four months along. They agree they will keep their baby despite the risk to their lives. Russ asks, “What will we do with it?” and Carol replies, simply, “We’ll love it.” They set up a shelter to hide Carol and baby.

Baby is born (we see only Carol’s silhouette on the wall), and they name him Jesse. Trouble ensues when neighbors George (Don Gordon) and Edna (Diane Cilento) Borden find out about Jesse and SPOILER ALERT: blackmail Carol and Russ into sharing him and more. What happens next becomes a parable of the battle between the culture of death and the spirit of human life and freedom.

Is Z.P.G. far-fetched? Not if you listen to anti-lifers. In 1968 Paul Ehrlich wrote, “We must cut out the cancer of population growth” and founded the non-profit group Zero Population Growth (today euphemistically called Population Connection). He also said “compulsory abortion” could be legal under the U.S. Constitution. Ted Turner once called for a 95% reduction in world population. Such inhuman notions continue to fester today, not least by Ehrlich himself: In 2014, he compared women having as many babies as they want to “throw[ing] as much of their garbage into their neighbor’s back yard as they want.” So much for the Carol McNeils of this world, who love babies and want to be moms.

The MPAA rated this film PG – “Some material may not be suitable for children.” There are scenes of marital embracing, but under the covers except for shoulders and Reed’s torso. Michael Campus directed. Frank De Felitta, Max Simon Ehrlich (no relation to Paul), and Tom Madigan were the producers and De Felitta and Ehrlich the scriptwriters. Jonathan Hodge was the composer and Michael Reed and Mikael Salomon the cinematographers. Dennis Lanning was film editor. Tony Masters was production designer and Peter Hajmark and Harry Lange the art directors. Margit Brandt was costume designer, Derek Meddings the creator of animatronic dolls, and Erling Jørgensen the set decorator.

— Dan Engler