The Drop Box: Rescuing Hundreds of Babies in South Korea

“This is a facility for the protection of life. If you can’t take care of your disabled babies, don’t throw them away or leave them on the street. Bring them here.”

– A sign on the Drop Box

It’s 1987 in Seoul, South Korea. A baby is born with cerebral palsy and a massive cyst on his left cheek that is cutting off blood flow to his brain, causing permanent damage. Without surgery, he will die, say the doctors, and with it, he will still be deformed. Fast forward to 2013: Eun-man is 26 years old. Though he has been bedridden his entire life with limbs bent in impossible positions and a vacuum that constantly suctions out saliva through a hole in his trachea, Eun-man has been instrumental in inspiring a mission that has saved the lives of hundreds of babies.

Meet Lee Jong-rak, Eun-man’s father and maker of Seoul’s “drop box.” Lee built this heated, blanket-lined box as a safe haven to welcome babies who might otherwise be abandoned to die on the street. After witnessing the problem of child abandonment in Seoul, Lee decided to do all he could to rescue and care for these babies, just as he cared for his own disabled son. “Through Eun-man, I learned about the dignity of valuable life,” he said. Since the drop box was installed in 2009, more than 652 babies have been saved. Lee’s life-saving work is the subject of the new award-winning documentary, The Drop Box, which premiered last week in theaters across the United States and Canada.

The Drop Box was directed by Brian Ivie, co-founder of Kindred Image, who was inspired to cover Lee’s work after reading about it in the Los Angeles Times in 2011. The 72-minute movie was funded through a Kickstarter campaign and was presented in association with Focus on the Family.

The Box

Lee and his wife, Chun-ja, operate the baby box from their home in Seoul which also serves as their church and now the ad hoc orphanage named Jusarang, meaning “God’s Love.” The snug box is built onto the side of their house facing the street and can also be opened from the home’s interior. A doorbell alarm alerts them and their small staff when a baby is placed inside.

During filming, director Ivie lived at Jusarang with Lee and his growing family. He was present for numerous “drop-offs” and he includes actual footage from one occasion in the movie. The scene is surreal as the “ding dong” echoes in the background, and Lee and his staff are seen hurrying towards the small hatch. Lee opens it, reaches in, and brings out a bundled child. Immediately, Lee embraces the baby, praying quietly, “Thank you, God, for saving this child’s life.” The orphanage staff then check the baby for a note, but there is none.

Lee describes the seven-step administrative process that he and his staff carry out upon receiving a baby. This includes informing local police, bringing the infant to the hospital for a check-up, registering the baby, and arranging to place the child with the city’s local adoption agency after a time of care at Jusarang. Sometimes they will remain at Jusarang, as is the case with 19 children whom the Lees have legally adopted.

An Urgent Need

As a Christian pastor known for his dedication to his disabled son, Lee was approached several times before the baby box existed to take in disabled babies. Desperate family members said they could not afford their care.

And so, take them he did.

In the movie, Lee tells of one child in particular whom he and his wife Chun-ja loved dearly. Hannah was surrendered into his care by a social worker on behalf of the girl’s 14-year-old mother who drank and did drugs while pregnant. Because Hannah suffered brain damage, doctors thought she would die any day, but instead, she lived for six more years in Lee’s care. Still clearly heartbroken, Lee says that after Hannah died, he vowed never to turn away any child with disabilities. “God, I will die for these children,” he said.

Lee describes the urgency of the problem of child abandonment, saying:

“People would often abandon their kids in front of our doorway…If they can’t afford to raise the baby, they leave the baby in front of someone else’s house and run away. It’s common practice. … We saw so many babies abandoned under any condition. We were so heartbroken seeing them. And we thought to ourselves, ‘What’s the best way to save these lives?’ We thought about this for many years. That’s why we made the baby box.”

Yet, not all abandoned babies are carefully left on doorsteps where they at least have a chance of being cared for properly. Even for the ones who are discovered on doorsteps, legal adoption is far from guaranteed. Due to deeply rooted cultural beliefs, the attitude towards adopting is generally negative in South Korea, and adopted children have been known to experience various forms of discrimination.

Besides the family’s poverty and the presence of a disability in the child, babies are also abandoned if they are born out of wedlock. Min Hwang, Director of the Women’s Hope Pregnancy Center in South Korea, says in the film that young unmarried mothers face pervasive social stigma that often results in extreme situations. She says that pregnant teens are kicked out of high school and sometime beaten by family members. She shared the troubling fact that every woman she met through her clinic was suicidal.

According to an annual report published by South Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare, 235 babies were reported as abandoned in 2012. Yet much child abandonment “happened in secret,” says Hwang. Now, because of Pastor Lee’s drop box, it is a “public issue” in Korea. Ivie hopes to broadcast The Drop Box on Korean television to continue to call for action and raise awareness.

Though the film doesn’t delve into South Korea’s adoption laws, Pastor Lee himself has spoken against changes made to the Special Adoption Law that was enacted in August 2012. It required that mothers register the births of their children with the government and keep their infants for at least seven days if they want to place them for adoption.

Lee and others contend that an unintended consequence of the new requirements was that more babies were being abandoned for the sake of maternal anonymity. He personally noticed the spike, saying that prior to the law’s change, an average of one or two babies per month came through the drop box. Soon after, it was about 19 babies per month. Because of this, Lee says the law should be considered for revision.

In September 2014, South Korea’s Department of Justice announced just this – that it was considering a revision to protect the birthmother’s anonymity during registration. But the revised law has not yet been passed. The number of abandoned babies reported in 2013 has risen close to 300.

Controversy

Pastor Lee’s drop box approach has garnered both acclaim and criticism. Some argue that because the box allows for an anonymous drop-off, it encourages child abandonment and is not a solution to the larger problem. To film director Brian Ivie’s credit, The Drop Box addresses these concerns, showing brief interviews with various government officials, and television and radio clips from questioning international media.

Lee himself agrees that the drop box is not ideal. Far from the ultimate solution, Lee says he prays that no baby will be brought to his box unless the baby’s life is in danger. “It’s a sad reality that I have to be doing this and I really hope the day will come that the baby box will no longer be needed,” he says.

As director Ivie put it: “The drop box was Pastor Lee’s desperate act of compassion: ‘I’m jumping in the river to save these children that are drowning.’”

Reflecting on her work at Women’s Hope Pregnancy Center, Director Hwang responded by saying that Lee’s drop box is life-saving and necessary until a “complete overhaul in thinking occurs.” “Because we are dealing with people,” she stresses, it will take time to come to a point when the culture as a whole recognizes the value of every life. “Until this is recognized,” Hwang says, “there will always be babies in dumpsters.”

The Message

There is a consistency to The Drop Box that is present in every scene – the message of hope that all lives matter.

Throughout the film, viewers are brought close to the children. Some have Down syndrome, others are missing limbs, and others are blind. All receive the warmth and generosity of Lee, his wife, and staff. In one scene, an interviewer asks one of Lee’s adopted sons whether his brother Eun-man has a purpose in life. Ru-ri replies in his 10-year-old, matter-of-fact way, “Of course he does. If not for him and the other babies, there would be no baby box and these babies wouldn’t have been saved.” Ru-ri, who does not have some fingers and toes, has high aspirations. “I want to inherit my dad’s work,” he said. “I will help and add my own effort, and eventually pass it down to my own child.”

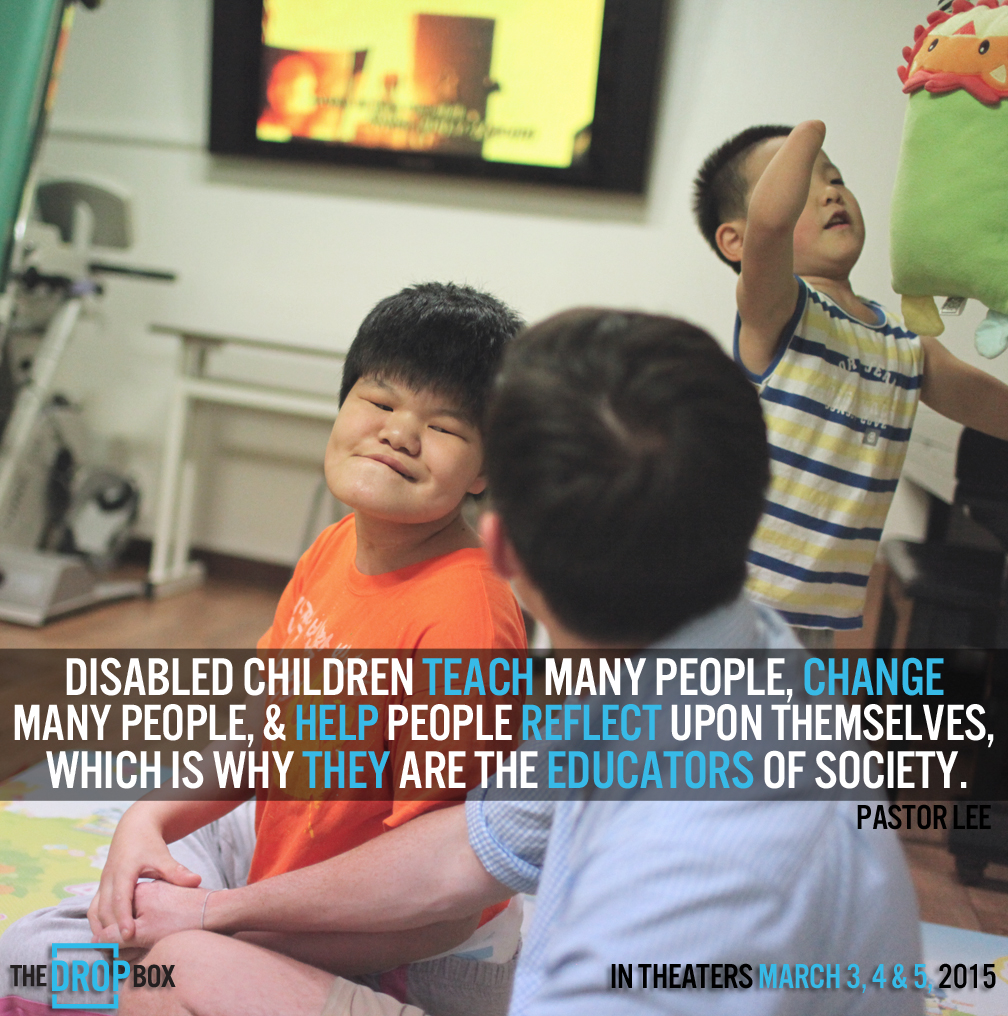

The Drop Box is a beautiful and rich tribute to Pastor Lee’s mission. At the same time that it presents a snapshot of a harsh reality, it also captures a moving love story. Lee summarizes his experience with humility, saying, “Disabled children teach many people, change many people, and help people reflect upon themselves, which is why they are the educators of society.” May Lee’s selfless mission and The Drop Box continue to inspire a culture that welcomes every life as having a unique purpose and deserving of protection and love.

*Due to popular demand, The Drop Box will have a special encore viewing on March 16, 2015 at select theaters. Check here for more information. A portion of the ticket proceeds go to Pastor Lee’s orphanage.

Genevieve Plaster is a research assistant for the Charlotte Lozier Institute.