Assisted Suicide’s Slippery Slope in Action: Washington State May Drop “Safeguards” Against Abuse

This is Issue 55 in the On Point Series.

Opponents of physician-assisted suicide (PAS) have long warned that there is a “slippery slope” from initially limited acceptance of the practice to a broader “right” to take the lives of the sick and elderly. PAS supporters have generally dismissed this claim as alarmist. In my home state of Washington, however, supporters are now embracing the claim, and urging lawmakers to ski down the slope.

Exhibit A is HB 1141, introduced at the beginning of the Washington legislature’s 2021 session with the express purpose of “increasing access to the provisions of the Washington death with dignity act.” In fact it does not increase “access” to that Act’s provisions – it radically changes those provisions, to invite the “abuses” that supporters had said the original Act would prevent.

HB 1141: Betraying the Voters’ Trust

Washington voters were persuaded to approve the Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) by ballot initiative in 2008 because supporters repeatedly made promises like this, from the initiative’s Voter’s Guide:

SAFEGUARDS WORK

There are multiple safeguards in Washington’s death with dignity law. These safeguards include independently witnessed oral and written requests, two waiting periods, mental competency and prognosis confirmed by two physicians, and self-administration of the medication. Only the patient – and no one else – may administer the medication.

Even at the outset, this promise by groups like “Compassion & Choices” (C&C) was misleading. The two witnesses were not truly “independent,” for example, as one of them could be an heir to the patient’s estate and/or a representative of the health facility with its own financial interest in premature death. These and other loopholes have been documented in many places.

But HB 1141 discards even the alleged safeguards, betraying the trust of those who voted for the current law thinking they could rely on them.

What new evidence has emerged to justify this change? It would be hard to claim there is any. Although required by the DWDA to release an Annual Report about the patients receiving a lethal drug overdose under the Act, the state Department of Health has released no information since July 2019, describing 2018 cases. That Report showed that in the law’s first decade, 1,667 lethal prescriptions were written and at least 1,210 patients died from the drugs. At least 203 patients died this way in 2018 — over five times as many as in 2009 when the law took effect.

These Annual Reports have also been less than useful in determining how often the “safeguards” are already abused. For example, the Department reports that in 2018 only 4% of the 251 patients who died from any cause after receiving the lethal prescription had been referred for a psychological evaluation. It did not say whether any of the 203 who died from taking the drugs were evaluated to detect treatable depression or other conditions impairing judgment.

Since supporters promised voters in 2008 that the DWDA’s safeguards would ensure that it allows relatively few patients to take their own lives, it is difficult to imagine how the legislature could decide that “too few” people are dying from a barbiturate overdose. But as it happens, we do not even know how many people have done so in the last two years.

HB 1141’s prime sponsor, Rep. Skyler Rude (R), seems to admit as much, because last year he sponsored a bill (HB 2419) funding a study to determine what the chief “barriers” were to wider use of the Act. In one stroke, the long-promised “safeguards” were redefined as troubling “barriers.” The legislature passed the bill, but it was vetoed by Governor Jay Inslee (D) – not on its merits, but because he was vetoing all legislation requiring public funds due to the state budget crisis created by the COVID pandemic. Now Rep. Rude and other sponsors have decided to skip collecting evidence and simply declare that there is an urgent need to eliminate the “safeguards.”

How the State Law Would Change

HB 1141 makes the following changes in the Act:

No two doctors: The DWDA requires agreement between an attending physician and a consulting physician on the patient’s terminal prognosis, mental competency, etc. Under HB 1141, one of these health care providers can be a physician’s assistant, osteopathic physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner. This person can claim the expertise to diagnose a terminal condition, predict that the patient is likely to die in less than six months, discern whether the patient requires a psychological evaluation, and sign the death certificate. (One troubling feature of the original DWDA, retained by the bill, is that it requires that the death certificate be falsified, listing the patient’s underlying illness as cause of death.) This person may also be in the employ of the other health care provider — for example, the physician’s assistant can be the assistant to that physician, compromising any independent judgment.

No genuine psychological evaluation: The DWDA requires that if either physician suspects clinical depression or another condition impairing the patient’s judgment, the patient must be evaluated by a psychologist or psychiatrist. The evaluation can now be done by a social worker or “mental health counselor.” While state law requires some kinds of counselors (such as “certified counselors”) to have certain qualifications, “mental health counselor” is simply included under the legal definition of a “counselor” – who can be any “individual” who counsels members of the public, for money:

“Counselor” means an individual, practitioner, therapist, or analyst who engages in the practice of counseling to the public for a fee, including for the purposes of this chapter, hypnotherapists. RCW 18.19.020 (7).

It is well known that even many physicians fail to detect such conditions in their patients. The new bill makes a mockery of the claim that depression and other impediments to sound judgment will be professionally evaluated before a patient is given lethal drugs.

No waiting period: In 2008, supporters emphasized that the patient’s initial oral request must be followed by a waiting period of 15 days before signing the final written request for lethal drugs; and 48 hours had to elapse between the written request and the writing of the lethal prescription. They said this would help prevent abuse, giving the patient time to get over a temporary depressive episode or to change his or her mind. This “safeguard” is now eliminated. The maximum required waiting period is a mere 72 hours. Even this is waived if the “qualified medical provider” thinks the patient may die in less than 72 hours. Oral and written requests can be simultaneous, turning the health facility almost into a drive-through suicide clinic.

Even trained physicians’ predictions of a patient’s life expectancy can be wrong. In 2016 and 2018, for example, the Annual Reports show that some patients expected to live less than six months had survived for over two years after obtaining the drugs. Moreover, the Reports do not report a patient’s life span until after a death certificate is filed. If a patient who received the drugs in 2018, but did not ingest them, lives for 20 years, we will not know this from the Department of Health until 2038. Each year’s Report therefore cites a significant number of patients whose status is simply unknown.

One might ask whether a prognosis of death within 72 hours is more likely to be reliable than more long-term predictions. Here my family’s personal experience is relevant.

Seventeen years ago, my wife was expected to die in far less than 72 hours. When a condition initially misdiagnosed as flu became much worse and her fever was raging, I drove her to the emergency room, where one of the medical staff announced: “This woman’s kidneys are shutting down.” What she had was toxic shock syndrome. We understood that her chance of survival was small. But through immediate aggressive treatment in the ER and then an intensive care unit, my wife was saved. After months of recovery at home she regained her full strength, and now at 65 years of age she is in robust health – and she has resumed her practice of regularly running for exercise, which the hospital staff said may have helped her survive this crisis.

Under the policy of HB 1141, would my wife or I have requested and received lethal drugs when we thought she was dying? For us personally, no. For others disoriented and panicked by such a dire situation, maybe so. But even for us, I shudder to think that the heroic effort made by these doctors and nurses may have been much less aggressive, and much less successful, once she was categorized under a law like HB 1141 as a patient for whom an immediate lethal overdose can be a treatment of choice. Such prognoses easily become self-fulfilling prophecies, even for patients who never thought of requesting what is misleadingly called a “death with dignity.” Once the prognosis is made, the right to health care easily takes a back seat to the “right to die with dignity” – and if a given patient declines to exercise that right, how much attention and expenditure of health care resources does that personal whim demand from others?

When a provider’s prognosis of imminent death does lead a patient to obtain and ingest lethal drugs, of course, that prognosis will never be proved wrong. In a sense the provider is “proved” right, after he or she falsifies the death certificate to report the underlying condition as cause of death. RCW 70.245.040 (2). “See, my prognosis was correct. This patient died in only two days, and it says so right here on the death certificate. What a brilliant physician’s assistant I am!”

An old joke in questionable taste is that a doctor gets to bury his mistakes. Now that joke becomes a disturbing reality.

Deadly drugs by mail or UPS: The DWDA required the lethal drugs, and instructions for their lethal use, to be dispensed by the physician or a pharmacist, and given only to the patient or “an expressly identified agent of the patient.” Concerned about the diversion of controlled substances into use as street drugs, it required that the drugs “shall not be dispensed by mail or other form of courier.” Even with that provision, it seems dozens of patients each year (as many as 64 in 2018) do not take the prescribed overdose, and no one seems to know what happens to these drugs. But HB 1141 eliminates that restraint entirely. Now delivery “may be made by personal delivery, by messenger service, or, with a signature required on delivery, by the United States postal service or a similar private parcel delivery entity.” Anyone who comes to the door can sign, and it seems unlikely that it will be the ailing patient; it could be the heir to the estate who wants to make sure Grandma obediently takes her medicine. No one will know what happens next, as the law does not require attendance by a medical provider. This cavalier treatment of deadly drugs endangers patients and others – an especially irresponsible act when the Seattle area saw an unprecedented doubling of deaths by overdose of controlled substances in the first weeks of 2021.

Increasing government scrutiny on facilities opposed to assisted suicide: The DWDA was promoted in 2008 as allowing individual freedom in end-of-life choices, as part of the right that has been called “the right to be let alone” by government. This claim was always misleading: Under current law, a range of other agents (from attending and consulting physician, to witnesses, to psychological consultant) are assigned by the State to have an equal or greater role in deciding who lives and who dies as compared with the patient. But HB 1141 reaffirms policies that compromise health care providers’ freedom of choice.

First, it reaffirms that a health facility opposed to assisted suicide may not prevent its premises from being used by its “qualified medical providers” to contract with patients to give them lethal drugs elsewhere. This may conflict with the federal law signed by President Obama in 2010, which forbids all states receiving federal aid under the Affordable Care Act to “subject an individual or institutional health care entity to discrimination on the basis that the entity does not provide any health care item or service furnished for the purpose of causing, or for the purpose of assisting in causing, the death of any individual, such as by assisted suicide, euthanasia, or mercy killing.” 42 USC 18113. A requirement to permit “contracting” seems intended to make the hospital assist in causing the patient’s death. It may also infringe on First Amendment constitutional rights, as the Supreme Court ruled in 2018 when invalidating a California law that required pro-life pregnancy aid centers to tell women where they can obtain an abortion.

Second, HB 1141 creates a new demand that each hospital must report to the Department of Health “its policies related to access to care regarding… End-of-life care and the death with dignity act,” and “must provide the public with specific information about which end-of-life services are and are not generally available” at the hospital. This will tell the State whether hospitals are acting in accord with the newly expanded law.

This seems to be a successor to the same sponsor’s bill of last year that was vetoed, which among other things called for study of the “barrier” created by “hospital, medical, hospice, and long-term care providers’ policies that restrict the participation in and the distribution of information about” the DWDA. Now hospitals themselves, presumably including religious hospitals, must provide the data for further state action against them.

These reporting requirements amend an existing state law that already required hospitals to report on their policies regarding “reproductive health care.” On abortion, Washington state law has gone far beyond simply allowing it without meaningful limit. Its constitution has its own “abortion rights” provision, and the state requires almost all private health plans in the state to cover abortion. Despite the lack of any such constitutional warrant for assisted suicide, that practice is now beginning to join abortion as something not only permitted but expected, a new standard of care for health care providers. Those who disagree will be watched.

The Arguments of Compassion & Choices

In a hearing before the House Committee on Health Care and Wellness on January 18, C&C spokesperson Kimberly Callinan defended HB 1141 with two arguments.

First, she said that the bill ensures that “the original intention of the law” is followed. This seems an outrageous claim when the bill deletes or greatly weakens the “safeguards” that supporters had claimed were essential to the law. The statement makes more sense if she meant that HB 1141 serves the “original intention” of C&C itself – an intention that was not revealed to the voters. Assisted suicide groups have always had a broader agenda, and they pursued more limited legislation in Oregon (1994) and then Washington (2008) only because previous efforts were defeated. Now, it seems, they think it is time to let people see the man behind the curtain — while pretending that there never was a curtain.

Ms. Callinan’s second claim is that other states have already approved laws very much like HB 1141, and Washington is “simply catching up” with them.

This, too, is a strange argument. Seven other states, and the District of Columbia, have legalized PAS. Of these eight laws:

- All have a requirement of two physicians.

- Four require the psychological evaluation to be done by a psychiatrist or psychologist. Three also allow a licensed clinical social worker; but one of these, Hawaii, makes a psychological evaluation mandatory rather than leaving it to the discretion of the attending and consulting physicians. One state, Maine, allows for “counseling” by a “state-licensed clinical professional counselor,” but still requires that a determination that the patient is “competent” to make a decision be made by a psychiatrist or psychologist. All these laws are stricter than HB 1141, which allows the (optional) evaluation to be made by a “mental health counselor” with no specified credentials.

- Six have a waiting period of 15 days between the first and second request, generally with a 48-hour period between the last written request and writing of the prescription. A seventh, Hawaii, requires 20 days. Only Oregon allows the waiting period to be waived when the physician thinks the patient may die before the period is up. No state law talks about 72 hours.

- Seven do not permit sending the lethal drugs by mail or parcel post; only California does. Maine even specifically requires that the drugs be dispensed “in person,” and New Jersey expressly prohibits sending them by mail or courier.

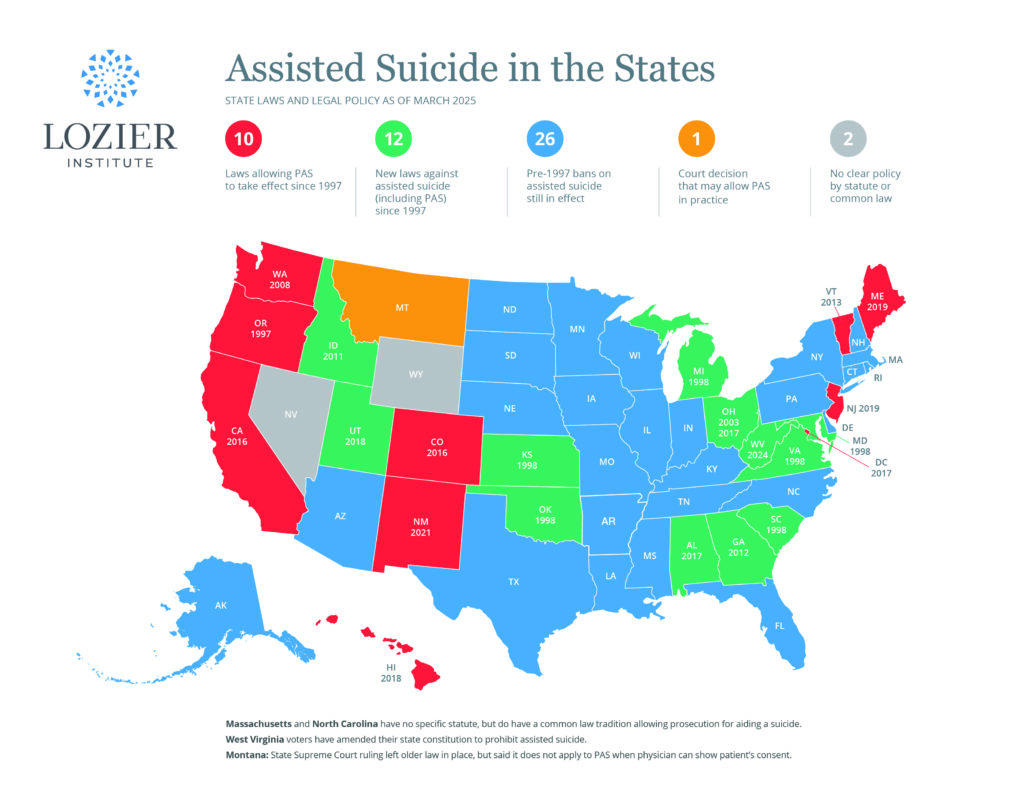

Moreover, beginning in 1997 when the Oregon law took effect, eleven states have passed new laws against PAS, and Congress has passed a law banning it in all federal health programs. If Washington wants to “catch up” with other states, why not catch up with the majority?

But if C&C persuades the Washington legislature to approve HB 1141 based on these misleading claims, it may well turn around and urge the other states to “catch up” with Washington.

The Future of the Assisted Suicide Agenda

If HB 1141 is approved, what is next? The bill’s prime sponsor, Rep. Rude, said at the January 18 hearing that he had also hoped to eliminate the Act’s requirement that lethal drugs be “self-administered,” but he has found this “more complicated” and hopes to address it later. As noted above, the DWDA’s proponents had insisted that “Only the patient – and no one else – may administer the medication.” But here also, it was the “original intention” of these proponents to authorize lethal injections by physicians, and they had included this in failed ballot initiatives in Washington (1991) and California (1992) before making a strategic decision to legalize assisted suicide first. That history is recounted elsewhere.

The move to administration of drugs by others may not be as big a step in Washington as in some other states. When the DWDA spoke of the drugs being “self-administered,” many people did not notice that it defined this word to mean the drugs are “ingested” by the patient. That word is ambiguous, as it could mean only that the patient absorbs or swallows an overdose provided by someone else. States passing later PAS laws have tried to eliminate that dangerous ambiguity – for example, in the Colorado law, “self-administer” means “a qualified individual’s affirmative, conscious, and physical act of administering the medical aid-in-dying medication to himself or herself to bring about his or her own death,” and California and New Jersey have similar language.

So Washington is a likely place to take the next step, moving from assisted suicide to outright homicide by doctors (and, under HB 1141, by others). On this point as well, other states can then be urged to “catch up” with Washington.

Policies like the Washington law already endanger the lives of weak and vulnerable patients whose problems deserve improved care, not a careless invitation to self-killing. HB 1141 promises to make this situation much worse — and it does not yet bring us to the bottom of the slope.

Richard Doerflinger, M.A., is an associate scholar at the Charlotte Lozier Institute