Dobbs and Medical Deserts: Will Pro-Life Laws Drive Away Doctors and Lead to Hospital Closures?

Executive Summary

- Post-Dobbs, pro-life states’ efforts to protect life have been met with pushback, including widespread claims that the laws are contributing to hospital closures and driving doctors away.

- A close look at the data shows that these claims are unjustified. Pro-life states continue to train medical students, recruit future doctors, and position themselves for further growth.

- Recent data from the Association of American Medical Colleges shows that across the country, total medical school enrollment has increased over the past five years – including in pro-life states.

- Pro-life states are still receiving many times more applications than they have spots available. While one study showed residency applications to pro-life states dropped slightly, it also showed that residency applicant rating of interest in programs in pro-life states was equal to that of other states. Additionally, when compared to the rest of the country, in the 2023 match cycle, 86.8% of all applicants still applied to residencies in pro-life states, and virtually all residency spots were filled.

- A review of press releases and media coverage around recent hospital closures shows that the hospitals shut down due to factors like financial problems and declining patient volumes, not abortion policy.

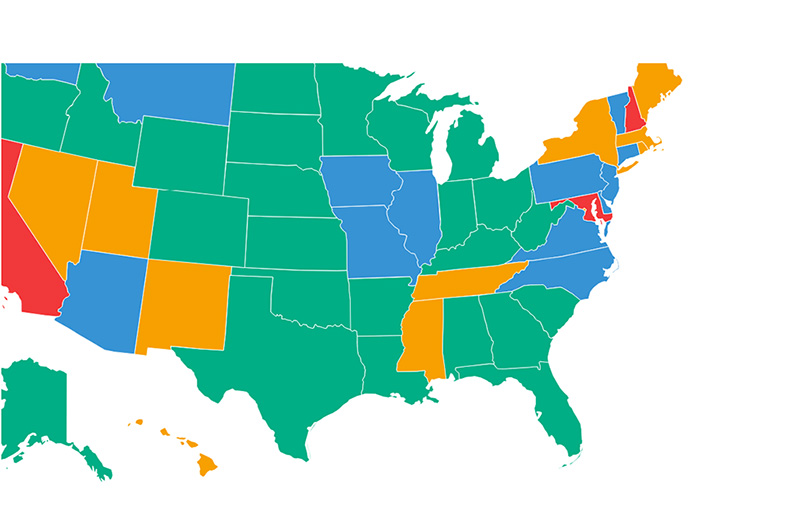

Two years after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, 24 states have pro-life laws in effect or in litigation.[1] These states’ efforts to protect life have been met with immense pushback, including widespread claims that the laws are contributing to hospital closures and driving doctors away. Pro-abortion think tanks like the Commonwealth Fund have implied that pro-life efforts will directly worsen such outcomes, “driv[ing] more maternal and reproductive health care providers to shut down or leave their states, deepening the crisis of access to maternity care.”[2] With the negative media coverage, residents of pro-life states may understandably have concerns that state laws could worsen gaps in medical care, causing harm to women and children in their state. However, a close look at the data and national trends shows that these claims are unjustified and the resulting concerns unnecessary. Pro-life states continue to train medical students, recruit future doctors, and position themselves for further growth.

Medical school enrollment

Some fear that pro-life laws will discourage future doctors from studying or training in pro-life states. However, recent data from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)[3] shows that across the country, total allopathic medical school enrollment has increased over the past five years – including in pro-life states.[4] During the 2023-24 academic year, enrollment in M.D.-granting medical schools in states with pro-life protections throughout pregnancy was up 6.6% from 2019-20 enrollment. In states that protect unborn children at other points in pregnancy (including heartbeat protections) and states whose pro-life protections are currently blocked as of publication, enrollment increased 7%. In states with no limits on abortion, enrollment rose 4.6%.

There has been no substantial shift in the share of future doctors studying in pro-life states. In 2023-24, medical students who were enrolled in M.D.-granting medical schools in the states that protect life from conception made up a sizable 22.9% of all medical students in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. This was virtually unchanged, and slightly higher, from 2019-20, when these states accounted for 22.7% of the total.

Additionally, pro-life states are well-positioned to train future OB-GYNs. Data from the American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) shows that of the 25 obstetrics and gynecology programs newly accredited in the past five years, over half (56%) are located in pro-life states.[5] If pro-life states continue to expand the training options for future doctors, they will likely see further growth in medical student enrollment each year.

Moreover, there has been an over 70% increase in osteopathic medical school enrollment in recent years.[6] Of 66 osteopathic training locations nationwide, over half (53%) are located in pro-life states.[7]

Residency applications

Declining OB-GYN residency applications have sparked worries that OB-GYNs will avoid pro-life states when deciding where to train. This would be particularly concerning since doctors are more likely to settle in states where they match as residents.[8] As a consequence, a decline in residency applicants could point to fewer doctors in these states long-term. A May 2024 analysis of AAMC data found that M.D. residency applicants (in all disciplines and in OB-GYN specifically) dropped for the second year in a row, a difference of 72 unique M.D. applicants, and that total applications fell by more than 100,000, although declines in applicants were most pronounced in pro-life states. The authors note that the drop in total applications follows efforts by AAMC and individual specialties to reduce the number of applications submitted by each applicant. The authors suggest that the states’ pro-life policies are the reason for the steeper decline compared to the rest of the country. However, they also note that “nearly all residency positions in OB/GYN were filled again this year, and a similar number of U.S. MD seniors matched into first-year positions this year and last year.” Importantly, the analysis shows that even as M.D. applicants dropped, D.O. applicants increased, including in pro-life states.[9]

Similarly, a recent study in the journal JAMA Network Open shows that while residency applications to pro-life states have dropped slightly when compared to the rest of the country, in the 2023 match cycle, 86.8% of total applicants still applied to residencies in pro-life states, down from 88.5% the previous year.[10] Virtually all residency spots were filled, and the authors comment that any decrease in residency applicants in pro-life states “may have minimal practical implications.” According to the National Resident Matching Program, in 2024, 2,143 total applicants applied for just 1,539 available OB-GYN residency positions.[11]

Pro-life states are still receiving many times more applications than they have spots available. In Nebraska, for instance, total OB-GYN residency applicants fell from 253 to 191 in 2024, sparking worries that Nebraska’s 12-week limit on abortion might be discouraging medical residents from applying to programs in the state.[12] However, taken in context, the number of applicants is far less concerning. According to ACOG, there are only two OB-GYN residency programs in Nebraska: University of Nebraska and Creighton University.[13] Both institutions match four residents per year,[14], [15] for a total of eight OB-GYN residency spots available in Nebraska each year.[16] The 191 applications to Nebraska residency programs far outnumber the placements available.

Furthermore, the JAMA study found that there was no significant difference in “signaling” – part of the application process by which applicants express strong interest in a given program – between pro-life and pro-abortion states. Since doctors may apply to a large number of programs to increase their chances of matching, “signaling” gives them the option to indicate their interest in the residency programs they would most prefer. Residency applicants had the same level of interest in programs in pro-life states as they did in programs in pro-abortion states.

Hospital closures and maternity care deserts

After an Idaho hospital closed its labor and delivery ward, citing Idaho’s pro-life law as a factor,[17] some argued that pro-life laws would lead to hospital closures throughout pro-life states.[18] However, the closure of hospitals across the country is a long-term problem that began well before Dobbs,[19] and even the Idaho hospital acknowledged abortion laws (from its perspective) are just one reason among many that contributed to the unsustainability of its childbirth services. In fact, the two main reasons cited were related to a lack of demand for services, a chronic problem for rural hospitals. The press release noted that “low [pediatric] patient volume is insufficient to attract candidates for pediatric hospitalists” and the hospital could not afford physicians working in temporary roles. Also, deliveries at this hospital “continued to decrease yearly” and they were delivering fewer than one baby a day on average when they closed, while a different hospital’s unit was updated to have neonatologists and obstetricians available 24/7. Ironically, the hospital’s labor and delivery ward closed due to a lack of births – a problem which, all else being equal, pro-life laws could be expected to help solve.

Rural hospitals are particularly at risk of closure. As many rural areas experience population decline[20] and increasingly fewer births,[21] the shrinking pool of patients puts a financial strain on local hospitals. Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses credentialling guidelines require a minimum staffing level in all labor and delivery units which may be unsustainable when a hospital has very few deliveries.[22], [23] Thus, low volume units may close while higher volume units increase in-house staffing to provide higher quality services. According to a July 2024 report by the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, more than 100 rural hospitals in the U.S. have stopped delivering babies in the past five years, and nearly 40% of the rural hospitals that do provide labor and delivery services experienced financial losses on overall patient services in 2022-23.[24]

Additionally, rural hospitals are chronically underfunded.[25] The Sheps Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill tracks rural hospital closures. Their data shows that in 2023, these closures were evenly split between pro-life and pro-abortion states: Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Texas.[26] A review of press releases and media coverage around each closure shows that the hospitals shut down due to factors like financial problems and declining patient volumes, not abortion policy.

“Maternity care deserts” – areas in our country with limited or no access to maternity care – are a serious problem that needs to be addressed. Women who live in rural areas must often travel long distances to obtain obstetric and emergency care. In addition, research shows that the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is higher in rural areas than in urban areas,[27] and more women in rural areas live in poverty, another important risk factor for maternal mortality.[28] It is to these underlying issues that policy solutions should be directed – permissive abortion laws are not the solution.

What factors attract doctors to a particular practice location?

Academic training programs and major medical institutions such as ACOG often teach and promote abortion as “essential health care,” “comprehensive care for patients,” and “reproductive autonomy and justice,”[29], [30] which may cause young obstetricians to mistakenly assume they will not be able to provide quality care in states with abortion limits. Yet, for most obstetricians, elective abortion provision is not part of their practice, regardless of their personal views on the issue. It is likely that most choose this profession because they love delivering babies and bringing new life into the world. For a variety of reasons, some ideological, some not, only 7-14% of obstetricians surveyed reported they would perform an abortion if requested by their patient.[31], [32]

Furthermore, a false narrative has become widespread that, in pro-life states, obstetricians cannot intervene to protect a woman’s life in a pregnancy emergency. In reality, every pro-life state permits a doctor to use his or her clinical judgment to determine if intervention is necessary due to a life-threatening medical emergency.[33] Appropriate education of doctors on pro-life laws will dispel this fear and confusion, and some states (Texas, Florida, South Dakota) are already working to counter this misinformation.

Like other Americans, doctors are often drawn to a geographic location by factors they feel will improve their quality of life. For example, they may choose a state with abundant outdoor activities, low taxes, or good schools for their children – features that many pro-life states have. Many will also be attracted to states that have implemented medical malpractice reforms and physician-friendly policies. Texas, for example, which has strong pro-life protections and malpractice reforms, has experienced a notable growth in physicians in recent years.[34] Pro-life states should not be afraid of losing medical care, but should instead continue to work to attract obstetricians who feel called to care equally for both their patients.

Tessa Cox is senior research associate at Charlotte Lozier Institute

Ingrid Skop, M.D., FACOG, is vice president and director of medical affairs for Charlotte Lozier Institute

[1] “Tens of Thousands of Lives Protected,” Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, accessed August 7, 2024, https://sbaprolife.org/lifesavinglaws.

[2] “2024 State Scorecard on Women’s Health and Reproductive Care,” The Commonwealth Fund, July 18, 2024, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/scorecard/2024/jul/2024-state-scorecard-womens-health-and-reproductive-care.

[3] “2023 FACTS: Enrollment, Graduates, and MD-PhD Data,” AAMC, accessed August 7, 2024, https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/2023-facts-enrollment-graduates-and-md-phd-data.

[4] There are 14 states with protections throughout pregnancy, of which 13 are included in this analysis: AL, AR, IN, KY, LA, MO, MS, ND, OK, SD, TN, TX, WV. There are 10 states that protect life at other points in pregnancy or whose protections are currently in litigation, of which nine are included in this analysis: AZ, FL, GA, IA, NC, NE, SC, UT, WI. There are 27 states that do not protect life or whose protections are permanently blocked, of which 23 are included in this analysis: CA, CO, CT, DC, HI, IL, KS, MA, MD, MI, MN, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VA, VT, WA. Alaska, Delaware, Idaho, Maine, Montana, and Wyoming do not have M.D.-granting medical schools and are not included in this analysis.

[5] ACGME – Accreditation Data System (ADS), available at: https://apps.acgme-i.org/ads/Public/Reports/Report/8.

[6] “Quick Facts,” AACOM, accessed August 21, 2024, https://www.aacom.org/become-a-doctor/about-osteopathic-medicine/quick-facts.

[7] “Osteopathic Medical Schools,” American Osteopathic Association, accessed August 21, 2024, https://osteopathic.org/about/affiliated-organizations/osteopathic-medical-schools/.

[8] See for ex. “AAMC 2023 Report on Residents: Table C6. Physician Retention in State of Residency Training, by State,” AAMC, accessed August 7, 2024, https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/students-residents/data/report-residents/2023/table-c6-physician-retention-state-residency-training-state.

[9] Kendal Orgera and Atul Grover, “States With Abortion Bans See Continued Decrease in U.S. MD Senior Residency Applicants,” AAMC | Research and Action Institute, May 9, 2024, https://doi.org/10.15766/rai_dnhob2ma.

[10] Maya M. Hammoud et al., “Trends in Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency Applications in the Year After Abortion Access Changes,” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 2 (February 7, 2024): e2355017, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.55017.

[11] “National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2024 Main Residency Match®,” National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2024. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/2024-Main-Match-Results-and-Data-Final.pdf.

[12] Sara Gentzler, “One Year after Abortion Law, Fewer Med Students Applying to Become Doctors in Nebraska,” Flatwater Free Press, May 24, 2024, https://flatwaterfreepress.org/one-year-after-abortion-law-fewer-med-students-applying-to-become-doctors-in-nebraska/.

[13] “Ob-Gyn Residencies by State,” ACOG, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.acog.org/career-support/medical-students/medical-student-toolkit/ob-gyn-residencies-by-state.

[14] “OBGYN Residency Program,” Creighton University, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.creighton.edu/medicine/residencies-fellowships/residencies-fellowships-omaha/residency-programs/obstetrics-and-gynecology.

[15] “Residency Program,” UNMC College of Medicine, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.unmc.edu/obgyn/residency/index.html.

[16] “Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency Programs,” Residency Programs List, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.residencyprogramslist.com/obstetrics-and-gynecology.

[17] “Closure of Labor & Delivery Services: Frequently Asked Questions” (Bonner General Health, March 2023), https://bonnergeneral.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/LD-FAQ-for-website.pdf.

[18] See, for ex., Senator Alex Padilla (D-CA) making such a claim during a recent congressional hearing on abortion access: https://www.c-span.org/video/?533895-1/hearing-abortion-access-economic-costs.

[19] “Rural Hospital Closures,” The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/.

[20] Kenneth Johnson, “Rural America Lost Population Over the Past Decade for the First Time in History,” University of New Hampshire, Carsey School of Public Policy, February 18, 2022, https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/rural-america-lost-population-over-past-decade-first-time-history.

[21] Tony Leys, “As a Baby Bust Hits Rural Areas, Hospital Labor and Delivery Wards Are Closing Down,” NPR, July 15, 2024, sec. Shots – Health News, https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2024/07/12/nx-s1-5036878/rural-hospitals-labor-delivery-health-care-shortage-birth.

[22] Kathleen Rice Simpson et al., “Incorporation of the AWHONN Nurse Staffing Guidelines into Clinical Practice,” Nursing for Women’s Health 23, no. 3 (June 2019): 217–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2019.03.003.

[23] Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses, “Standards for Professional Registered Nurse Staffing for Perinatal Units,” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 51, no. 4 (July 1, 2022): S5–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2022.02.003.

[24] “Addressing the Crisis in Rural Maternity Care” (Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform, July 2024), https://ruralhospitals.chqpr.org/downloads/Rural_Maternity_Care_Crisis.pdf.

[25] Ibid.

[26] “Rural Hospital Closures,” The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

[27] Katharine A. Harrington et al., “Rural–Urban Disparities in Adverse Maternal Outcomes in the United States, 2016–2019,” American Journal of Public Health 113, no. 2 (February 2023): 224–27, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307134.

[28] Ingrid Skop, “Handbook of Maternal Mortality: Addressing the U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis, Looking Beyond Ideology,” Charlotte Lozier Institute, January 6, 2023, https://lozierinstitute.org/handbook-of-maternal-mortality-addressing-the-u-s-maternal-mortality-crisis-looking-beyond-ideology/.

[29] “Abortion Is Essential Health Care,” ACOG, accessed August 8, 2024, https://www.acog.org/advocacy/abortion-is-essential.

[30] “Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard University Complex Family Planning Fellowship,” Brigham and Women’s Hospital, accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.brighamandwomens.org/obgyn/for-medical-professionals/bwh-harvard-complex-family-planning-fellowship.

[31] Sheila Desai, Rachel K. Jones, and Kate Castle, “Estimating Abortion Provision and Abortion Referrals among United States Obstetrician-Gynecologists in Private Practice,” Contraception 97, no. 4 (April 2018): 297–302, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2017.11.004.

[32] Debra B. Stulberg et al., “Abortion Provision Among Practicing Obstetrician–Gynecologists,” Obstetrics and Gynecology 118, no. 3 (September 2011): 609–14, https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822ad973.

[33] Mary Harned and Ingrid Skop, “Pro-Life Laws Protect Mom and Baby: Pregnant Women’s Lives Are Protected in All States,” Charlotte Lozier Institute, September 11, 2023, https://lozierinstitute.org/pro-life-laws-protect-mom-and-baby-pregnant-womens-lives-are-protected-in-all-states/.

[34] Sean Price, “Help Wanted: Texas’ Physician Growth Strong, but Recruitment, Diversity Still Needed,” Texas Medical Association, December 2022, https://www.texmed.org/Template.aspx?id=60809.