Prenatal Tax Credits and Child Support for the Unborn: A Literature Review

This is Issue 29 of the American Reports Series.

Executive Summary

- Prenatal tax credits and child support for the unborn have a firm foundation in common law, as well as statutory and judicial precedent, though that foundation has drawn increasing criticism by those advocating for a legal right to abortion.

- Prenatal tax credits at the federal, state, and local levels hold out the promise of potentially enhanced birth weights and improved food stability, especially if the credit is provided monthly, is refundable, and is worth at least 10% of the federal child tax credit amount.

- By 2020, 37 states or territories had laws providing that some pregnancy and/or childbirth expenses be paid for or reimbursed by the father; 19 had expanded support expenses beyond that; and two had either mandated pregnancy cost-sharing for the father or provided full child support eligibility for the unborn legally equivalent to that of postnatal children.

- The variable state and federal policies on both issues present a palette of opportunities for increasing support for the unborn.

Introduction

This literature review examines peer-reviewed and other authoritative publications addressing the provision of child support and tax credits for the unborn, focusing on the legal foundation for such policies; the evidence that tax credits have beneficial impacts on expectant mothers and their unborn children, as well as the pattern of such tax credits at the federal and state levels; and the evolution of prenatal child support at federal and state levels.

First, this study presents research demonstrating a firm foundation in common law, as well as statutory and judicial precedent, for such policies.

Second, it lays out samples from the prodigious literature demonstrating the likely benefits of tax credits to expectant families at the federal, state, and local level. Such benefits include potentially enhanced birth weights and improved food stability, especially when the credit is provided monthly, is refundable, and is worth at least 10% of the federal child tax credit amount. The study also provides updates to previous research on which states have such credits.

Third, the review will map out the long, winding historical path towards child support for the unborn, finding that by 2020, 37 states or territories had laws providing that some pregnancy and/or childbirth expenses be paid for or reimbursed by the father; 19 states or territories had expanded support expenses beyond that to include costs like insurance, lost wages, confinement, postnatal care, and recovery; and two had either mandated pregnancy cost-sharing for the father (Utah) or provided full child support eligibility for the unborn legally equivalent to that of postnatal children (Missouri).

Overall, a review of this literature suggests a pattern of variable and inconsistent state and federal policies rife with opportunities for improving the security and support of innocent life.

I. Legal Foundation

Legal discussions of prenatal child support and tax credits revolve around the degree to which unborn children are recognized as human – entities with rights under the law – and the legal implications for parental responsibilities.

Discussion of unborn rights under the law dates back centuries. Legal references stretch back at least to Blackstone’s Commentaries, published between 1765 and 1769, which state that, “Life is the immediate gift of God, a right inherent by nature in every individual; and it begins in contemplation of law as soon as an infant is able to stir in the mother’s womb.” Blackstone also writes that a child “in the mother’s womb, is supposed in law to be born for many purposes,” including having a legacy made to it, a guardian assigned to it, or an estate limited to its use, “as if it were then actually born.” [1] Similarly, in the American case of Hall v. Hancock (1834) the Massachusetts Supreme Court found unanimously, citing multiple English cases, that “a child is to be considered in esse [in being] at a period commencing nine months previously to its birth,” and “a child will be considered in being, from conception to the time of its birth in all cases where it will be for the benefit of such child to be so considered.”[2] The Georgia Supreme Court also acknowledged the legal personhood of the unborn, from conception onward, in 1849.[3] To the extent that executives, judges, and legislators respect such early common law sources, then, both prenatal child support and tax credits rest on firm footing.

That said, the use of that footing varies radically depending on the perspective of the legal expert, usually because of the expert’s stance on abortion. On one hand, some modern legal scholars have climbed from this footing to a recognition of the full legal personhood of the unborn under the Fourteenth Amendment,[4] and others have argued for the same conclusion in part on the basis of the historical usage of the term “person” in legal contexts, similar to the way in which corporations are recognized as legal persons.[5]

On the other hand, many scholars and legal experts have contended that unborn children do not, or need not, possess the same legal rights as born individuals. For instance, as early as 1960, one legal scholar made the case that the legal status of an unborn child as a “person” is not essential for recovery in cases of prenatal injuries, asserting that such recognition is a legal fiction unnecessary for the recovery of damages.[6]

More and more, as the argument over abortion matured, critics of prenatal personhood argued implicitly that granting legal rights to the unborn would militate against their policy goal of authorizing fetal termination. Once their position found purchase at the Supreme Court, scholars could simply cite the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, which directly denied the existence of prenatal personhood, provided legal protections for life-ending procedures on unborn children in a trimester system, and implied that legal personhood begins postnatally.[7]

With that support removed in the wake of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, personhood’s legal critics have renewed attacks on the concept, fearing the possibility of a national abortion ban, whether enacted by a piece of federal legislation or a national Constitutional amendment.[8] Other critics have pointed to personhood’s potential implications for in vitro fertilization (IVF), obstetric emergencies mistaken for intentional abortions, and deaths of unborn children whose mothers engage in behaviors risky to fetal development like drug use.[9]

Thus, in the U.S., prenatal personhood remains controversial among legal scholars, and likely will remain so as long as abortion remains a salient issue.

Similarly, in international contexts, legal recognition of the unborn varies. For instance, United Nations and other multilateral human rights treaties, though broadly granting rights to “everyone” or all “human beings,” do not precisely define these terms, including whether they apply to the unborn.[10] Copelon et al., for example, note that the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR),[11] “explicitly premises human rights on birth,” and other international and regional human rights treaties likewise “clearly reject claims that human rights should attach from conception or any time before birth.”[12] Philip Alston, in a 1990 paper published in Human Rights Quarterly, similarly argues that the 1989 U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child,[13] which by contrast to the Declaration of the Rights of the Child is a binding treaty with legal obligations for signatory countries, does not explicitly recognize a right to life from the moment of fertilization.[14]

By contrast, the 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child, though non-binding, explicitly provides for care and safeguards “before as well as after birth.”[15] Likewise, the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[16] states that the death penalty is not to be carried out on a pregnant woman, perhaps implying some form of legal status for the unborn.[17] Moreover, the 1986 African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights,[18] a.k.a. the Banjul Charter, “makes explicit reference to a pre-natal right to life.”[19]

Thus, at home and abroad, the question of unborn personhood remains fraught with disagreement and controversy. Consequently, courts and legal scholars are unlikely either to extrapolate common law or international conceptions of the status of the unborn into coverage of either prenatal tax credits or child support, but neither are they likely to strike down such tax credits or child support as alien to legal precedent.

Accordingly, both come down to policy discussions of evidence of their benefits to women and children and consideration of their legislative merits.

II. Evidence Supporting Unborn Tax Credits

Extensive research at the federal, state, and local levels largely suggests that tax credits can help alleviate the financial burden on expecting families, with positive benefits for both the unborn child and mother.

At the federal level, for instance, evidence suggests that the use of refundable child tax credits has stabilized high-risk pregnancies and increased food availability. For example, an older study based on the Gary Income Maintenance Experiment, one of a coordinated series of tests funded by the U.S. government of the impacts of negative income tax plans like refundable tax credits, found that such interventions led to a significant health response for children of women who had high-risk pregnancies.[20] They also, however, carried risks of significant work disincentives for husbands and larger still disincentives for female heads of households.[21] More recently, a 2015 study by Hoynes et al. found that a $1,000 benefit increase in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) leads to a 2 to 3% decline in low birth weight, potentially based on more prenatal care, less negative health behaviors (including smoking), and a shift from public to private insurance coverage.[22] Some critics, however, question Hoynes et al.’s findings, charging that failed placebo tests undermine some reported effects, that the study lacks a plausible mechanism linking the EITC and maternal smoking, that the waning of the crack epidemic is a possible confounding factor, and that other policies directed at poor women eliminate the statistical effect of the EITC.[23]

In 2021, due to the COVID-19 crisis, the U.S. expanded the federal child tax credit for up to $3,600 per year for children five and under, and up to $3,000 a year for children and adolescents ages six to 17, made it fully refundable, and allowed qualifying families to receive half of the estimated credit in advance.[24] Federal policymakers also experimented with monthly payments, which 47% of surveyed recipients reported spending on food.[25] One study likewise recommended that state policymakers consider such a monthly payment option to make their states’ child tax credits in particular most effective.[26] A New Jersey study of the 2021 federal child tax credit replicated the aforementioned finding, with 34.1% of surveyed recipients reporting they spent some of the resources on food, the most commonly selected response.[27] According to the same study, 9% of those surveyed spent at least some of their tax credit on childcare, with similar percentages in New York (8.3%), Pennsylvania (11.2%), Connecticut (10.8%), and Delaware (8.8%). Today, the federal government makes an EITC available to those who have worked, earned income under $63,398, and have investment income below $11,000 in the tax year 2023.[28]

Likewise, at the state level, multiple studies have found benefits of tax credits during pregnancy. For example, in 2010 research emerged suggesting that providing more generous state EITCs during the prenatal period also increased children’s birth weights and reduced maternal smoking, though with varying effects across maternal ages.[29] Another study found that state-level EITC generosity is associated with improved birth outcomes, and that states with refundable EITCs (that is, those that provided a net negative tax rate) had the largest increases in birth weights and reductions in prevalence of low-weight births.[30] A similar 2019 study found that any level of state EITC is associated with better birth outcomes, with the largest effects seen among states with more generous EITCs, and that black mothers experience larger percentage point reductions in the probability of low birth weight and increases in gestation duration.[31] Thirty states and areas currently have an EITC, 25 of which are refundable, 23 of which can meet or exceed 10% of the federal EITC, and 18 of which are both refundable and can meet or exceed 10% of the federal EITC.[32] Moreover, Georgia explicitly permits prospective parents to take the state’s dependent child income tax deduction during pregnancy,[33] and in 2023 Utah passed a pregnancy tax break as well.[34], [35]

Finally, one study – unique in that it examined a local tax credit program’s benefit for pregnant mothers – found that a Montgomery County, Md. EITC program decreased the probability of low birth weight by 1.9 to 2.4 percentage points among likely eligible mothers.[36]

Taken together, this evidence suggests that prenatal child tax credits could have significant positive economic benefits for expecting families, with reduced hunger during pregnancy, decreased negative maternal behaviors, and improved birth outcomes as potential follow-on rewards.

Theoretically, an infrastructure to provide prenatal tax credits already exists, given that traditional post-birth Child Tax Credits (CTCs) are in place at the federal level, as well as in 15 states Specifically, in 2013, Oklahoma became the first state to pass a CTC, set equal to 5% of the federal child tax credit. In 2017, North Carolina enacted a law allowing a deduction of $500-$2,500 for each child for whom the taxpayer is allowed the federal child tax credit, depending on income and filing status. In 2018, Idaho set its nonrefundable child credit rate at $205, and Maine established a $300 nonrefundable dependent exemption tax credit for each qualifying child and dependent for whom the federal child tax credit was claimed.[37] In 2019, California also passed a CTC, including a full benefit for significantly impoverished families, namely $1,000 for families with children under six years old and earnings below $25,000, phased out by $30,000. The state eliminated the earnings requirement and indexed the CTC’s value to inflation in July 2022.[38] That same year, New Jersey,[39] Colorado,[40] and Vermont[41] created permanent CTCs, with the latter providing a fully refundable credit of $1,000 for those with adjusted gross income of $125,000 or less. Also in 2022, New Mexico created a CTC set to expire in 2031,[42] and New York provided a one-year increase to its Empire State Child Credit.[43], [44] In 2018, Idaho[45] and Maine[46] adopted nonrefundable dependent credits, and, starting in 2024, Massachusetts modified its refundable credit to eliminate its two-dependent cap and increase its amount from $180 per dependent child et al. to $440 on a permanent basis.[47]

In addition, Rhode Island[48] and Connecticut[49] provided one-time or temporary child tax rebates, and Maryland passed a temporary one that it subsequently expanded and made permanent.[50], [51] In 2023, Minnesota and Oregon created new refundable CTCs, Maine made its CTC refundable, and Utah created a new, nonrefundable CTC. The same year, Arizona passed a temporary family tax credit that is roughly equivalent, as well.[52] In 2024, Utah expanded its CTC to include children under five years old, though it remains nonrefundable.[53] Finally, the District of Columbia has put in place a refundable EITC that, for individuals with qualifying children, is 70% of the federal earned income tax credit for tax years 2022 – 2024. For tax year 2023 in particular, this credit was to be paid in 12 monthly installments after the tax return was processed for credits worth$1,200 or more.[54]

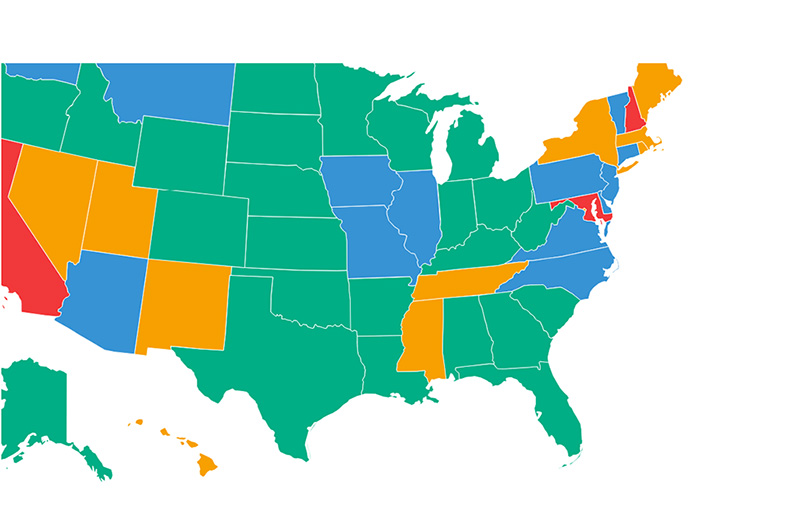

As of the time of writing, therefore, at least 15 states have CTCs – though most of these states, except for Oklahoma, Utah, and Idaho, hardly appear likely to acknowledge prenatal personhood by applying those credits to the unborn (See Figure 1 below and the Appendix).[55]

Figure 1: Child Tax Credit Status, by State (2024)

Figure 1: Child Tax Credits by State, including refundable, nonrefundable, and temporary child tax benefits, updated to 2024 (Sources: Collyer et al., 2022; Birle, 2023; Davis & Butkus, 2023; Taylor, 2023; Bascome, 2024; Maxey, 2024; Roche, 2024).

III. Evolution of Unborn Child Support

Statutes providing child support for the unborn date back centuries, and now form a patchwork across the country. More generally, legal attempts to deal with child support in the common law system on which American jurisprudence rests date back at least to a 1575 English statute providing that upon the birth of a child of unmarried parents , the local justices of the peace could compel the mother or reputed father to contribute regularly to his or her support.[56] Thus, it is not surprising that the question of whether such support should or should not extend prenatally is also old, as laid out below.

A. State Level

Policies regarding prenatal child support at the state level can be found as early as the 18th Century and have developed over the past few decades to the point where some minimal recognition of financial responsibility to the unborn has become nearly universal.

The earliest record of a state making some provision for unborn child support came from Georgia, which passed the so-called Bastardy act in 1793, providing for judgment against a “person sworn to be the father” to give security for the maintenance and education of one or more children “born or to be born” until the age of 14.[57] The Georgia law also included the expense of “lying-in,” a 15th-Century term traditionally referring to the state both during and consequent to childbirth,[58] but more specifically defined in this case as boarding, nursing, and maintenance while the mother of the child is confined, or recovering from childbirth.[59]

In Pennsylvania, a provision in Smith’s Laws (1810)[60] states that “on a conviction of bastardy, the uniform practice has been, to make an allowance for lying-in expenses, and a gross sum for the support of the child from its birth to the time of judgment.”[61] A 1917 article on Pennsylvania law similarly noted that a “girl who desires to obtain from the father of her child support for the child and lying-in expenses for herself” may do so “any time within the statute of limitations, i.e., at any time within two years from the date of conception – (not from the date of the child’s birth)” [emphasis in original], though “the trial will never take place until after the birth of the child.”[62] The same article goes on to relay that in at least one case the order for a father to pay for expenses related to childbirth “has included expenses of the mother while incapacitated prior to actual labor; and if the mother is totally incapacitated for several weeks before the arrival of the child, there would seem to be no valid reason why the act should not be liberally construed in this regard.” Finally, the article notes that if “the child is still-born it is the present practice to award the mother her lying-in expenses.”[63]

Similarly, in 1848, Florida approved an act to provide for the support and maintenance of “bastard” children, which applied to “any single woman who shall be pregnant or delivered of a child,” and “condemned” a man found guilty of “bastardy” in the case to pay no more than 50 dollars, as well as all necessary incidental expenses attending the birth of the child, yearly for ten years, with the explicit proviso that if the child should not be born alive or should die after birth the bond should be void.[64] During the legislative session beginning in 1849, Wisconsin added an analogous requirement, including in its ambit a “female … who shall be pregnant with a child, which if born alive may be a bastard,” and committing one found to be the father to pay or post bond for expenses of the town including those incurred for “the care and support of such child prior to the giving of such bond,” as well as for “the lying in and the support and attendance upon the mother of such child during her sickness.”[65]

Arkansas enacted a similar law in 1875 requiring the father to pay for the lying-in expenses of the mother, noting that “[b]ills and invoices for pregnancy and childbirth expenses and paternity testing are admissible as evidence” in court as “prima facie evidence of amounts incurred for such services or for testing on behalf of the child,” and therefore amounts for which the father was liable, a law which is still in place today.[66] By 1874, New York had a law in force applying inter alia to a woman “pregnant of a child likely to be born a bastard,” specifying that the reputed father of such a child should be liable for “any expense for the support of such child, or of its mother during her confinement and recovery therefrom” [“confinement” being a synonym for lying-in[67]], and explicitly mentioning a sum to be paid weekly or otherwise for “the support of such bastard, or such child likely to be born a bastard,” that is, prenatally where applicable.[68]

Finally, in 1921, Delaware enacted a similar statute requiring the father of an “illegitimate child” to pay the “trustees of the poor” for any expenses they incur for that child while “under 16 years of age,” specifying that the proceedings may be instituted by a woman while still pregnant, that the payment may include “lying in expenses,” and that the doctor who delivered the child may be compensated as well.[69] The 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, then, saw numerous states codify various forms of child support that applied prenatally.

In 1922, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL) began to adopt a series of recommended model legislation for states to address paternity and support obligations in particular,[70] starting with the Uniform Illegitimacy Act. Section 1 of that Act “imposes on the father a liability to pay the necessary expenses of the mother’s pregnancy and confinement.”[71]Along these lines, in 1925 California amended a measure related to “Abandonment and Neglect of Children” providing criminal penalties for parents willfully omitting to furnish necessities to their minor child, including a provision stating that a “child conceived but not yet born is to be deemed an existing person insofar as this section is concerned,” which astonishingly enough still exists in the state’s law today.[72]

Beginning in 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court began to invoke the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause to eliminate the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate children across a wide swath of areas, one exception being the right of intestate succession. This culminated with the Uniform Parentage Act (UPA), which NCCUSL originally approved in 1973 as recommended model legislation for states, which removes the legal status of illegitimacy, and instead provides a framework for establishing paternity and support obligations, extending rights for children born out of wedlock, and eliminating the legal concept of “bastardy” and the limitations it put on child rights.[73] In particular, the UPA contained a provision that “[t]he judgment or order may direct the father to pay the reasonable expenses of the mother’s pregnancy and confinement.”[74]

States began to adopt the UPA thereafter, expanding or contracting it as each deemed appropriate. For instance, in 1975, Hawaii adopted the UPA),[75]and in 1980- Minnesota adopted it as well.[76] Going further, in 1986, Missouri enacted a measure providing to unborn children “all the rights, privileges, and immunities available to other persons, citizens, and residents of this state”[77] by that measure, at least, making the Show Me State the first with full prenatal child support.

The UPA itself was amended in 2002, including expanded provisions dealing with prenatal health with respect to genetic testing, as well as acknowledging that the gestational mother has a (then, allegedly) “constitutionally-recognized right to decide issues regarding her prenatal care.”[78] Still, as one might presume from such language, not every state has adopted the UPA in all its forms; in fact, only eight states have adopted the latest version from 2017,[79] the provisions of which include seeking to eliminate distinctions between traditional and same-sex parents. The eight states that have adopted it are California, Washington, Colorado, Maine, Vermont, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island.[80]

Regardless of the UPA’s lack of universal state adoption, according to research conducted by Daniel Gump, in 2020 all federal jurisdictions had some prenatal child support requirement, as well as reciprocity across state lines; 37 states or territories had laws facilitating pregnancy and/or childbirth expenses to be paid or reimbursed by the father; and 20 states or territories had expanded prenatal child support expenses to include costs like lost wages, confinement, and so on.[81]

Some states, however, are going significantly further. In 2021, Utah enacted a new law requiring fathers to pay half of a mother’s out-of-pocket pregnancy costs, becoming perhaps the first state to mandate prenatal child support.[82] Finally, in March, 2024, the Kentucky Senate passed a bill granting the right to collect child support for unborn children, allowing a mother to seek support retroactively for pregnancy expenses up to a year after birth, though at the time of the report, the bill had yet to be signed into law.[83]

This wide range of state-level unborn child support policies presents an opportunity to increase protections for expecting mothers and their unborn babies in states lagging behind, as well as to enact strong uniform or even preemptive measures at the federal level.

B. Federal Level

Currently, at the federal level, child support for the unborn has advocates but meaningful legislation has not yet passed in Congress. Some federal recognition of the costs of pregnancy in child support matters came with the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act in 1996,[84] which amended the Social Security Act to allow bills for the costs of pregnancy and childbirth as evidence in paternity courts. Support for going further, however, appears to exist. In 2022, for instance, survey research suggested that 47% of the American public backs child support payments beginning when the child is conceived, with only 28% opposed and 25% unsure.[85] Accordingly, in July of 2022, U.S. Senators introduced the Unborn Child Support Act,[86] which would allow a mother to collect child support after birth, retroactively back to the point of conception as determined by a physician. In 2024, the bill was reintroduced in the new Congress on a bicameral basis.[87] Such measures, however, still have yet to become federal law.

IV. Conclusion

The literature on unborn child support and tax credits spans legal, economic, and policy dimensions of the issue. The legal dimension suggests a stable basis for enacting or enhancing such policies, with a warning of potential opposition because of their proximity to abortion law. The economic dimension makes relatively clear that tax credits applied to expectant families, especially when refundable and/or 10% or more of the federal credit when at the state level, have tangible positive outcomes for unborn children and their mothers. Finally, the evolution of unborn child support policies at the state and federal levels reveals the potential to bring more benefits to bear to support innocent life and the mothers who bring this life into the world.

Christopher C. Hull, Ph.D., is the President of Issue Management Inc., a full-service public affairs firm focused on achieving policy results. Dr. Hull holds a Ph.D. with distinction in American Government from Georgetown University, and an undergraduate degree magna cum laude in Comparative Government from Harvard University. He has served as Chief of Staff in the U.S. House of Representatives; the Majority Caucus Staff Director of a State Senate; Executive Vice President of a major national think tank, and Legislative Assistant/Legislative Correspondent in the U.S. Senate. He is the author of Grassroots Rules (Stanford Press, 2007), as well as more than 100 book chapters, peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, and op-eds.

The author wishes to thank the Charlotte Lozier Institute staff for their contributions, especially Deputy Editor Ben Cook for his excellent research recommendations and assistance with sources.

Appendix: Child Tax Credit Status by State, 2024

[1] Blackstone, W. (1765-1769). Commentaries on the Laws of England, v. I, Bk. I, p. 79, https://lonang.com/wp-content/download/Blackstone-CommentariesBk1.pdf.

[2] Cited in Finnis, J., & George, R. (2021). Equal Protection and the Unborn Child: A Dobbs Brief. Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, 45, p. 940, https://journals.law.harvard.edu/jlpp/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2022/10/7-JLPP-45_3-Finnis-George.pdf.

[3] Ibid., p. 941.

[4] See, for ex., Gorby, J. D. (1979). The “Right” to an Abortion, the Scope of Fourteenth Amendment Personhood, and the Supreme Court’s Birth Requirement. Southern Illinois University Law Journal, 4, 1-36, https://repository.law.uic.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1313&context=facpubs; and Craddock, J. (2017). Protecting Prenatal Persons: Does the Fourteenth Amendment Prohibit Abortion? 40 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 539 (May 15), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2970761.

[5] See, for ex., Paulsen, M.S. (2013). The Plausibility of Personhood. Ohio State Law Journal, 74(1), 13-73, https://kb.osu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ef4134ef-912a-5aca-891d-4eee8b5b913d/content.

[6] LeVan, G. (1960). Torts – Prenatal Injuries – Characterization of Unborn Child as a “Person” Immaterial to Recovery. Louisiana Law Review, 20(4): 810-814, https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2854&context=lalrev.

[7] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

[8] Manninen, B.A. (2023). A Critical Analysis of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization and the Consequences of Fetal Personhood. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. Published online by Cambridge University Press, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/cambridge-quarterly-of-healthcare-ethics/article/critical-analysis-of-dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization-and-the-consequences-of-fetal-personhood/A8803B46F4A0C9157C639289F463A83C.

[9] Daar, J. (2023). Where Does Life Begin? Discerning the Impact of Dobbs on Assisted Reproductive Technologies. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 51(3), 518–527, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-law-medicine-and-ethics/article/abs/where-does-life-begin-discerning-the-impact-of-dobbs-on-assisted-reproductive-technologies/A88ECD6168D2DB11F2CD6F9F3A0AADD0#.

[10] de Freitas, S. & Myburgh, G. (2011). Seeking Deliberation on the Unborn in International Law. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal (PER/PELJ) vol. 14, no. 5., https://scielo.org.za/pdf/pelj/v14n5/v14n5a02.pdf; Ibegbu, J. (2000). Rights of the Unborn Child in International Law: v. 1. Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

[11] United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights (General Assembly Resolution 217 A), December 10, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

[12] Copelon, R., Zampas, C., Brusie, E., & deVore, J. (2005). Human Rights Begin at Birth: International Law and the Claim of Fetal Rights. Reproductive Health Matters, 13(26), 120–129, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16291493/.

[13] United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child (General Assembly Resolution 44/25), November 20, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child, cited in de Freitas & Myburgh (2011).

[14] Alston, P. (1990). The Unborn Child and Abortion under the Draft Convention on the Rights of the Child. Hum Rts Q 12(1), February, 156-178, https://www.jstor.org/stable/762174.

[15] United Nations (1959). Declaration of the Rights of the Child (General Assembly Resolution 1386 (XIV), item 64, p. 19), November 20, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/195831?v=pdf&files=#files.

[16] United Nations (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI)), December 16, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights.

[17] de Freitas & Myburgh (2011).

[18] Organization of African Unity (1986). African (Banjul) Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Adopted 27 June 1981, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3 rev. 5, 21 I.L.M. 58 (1982), entered into force 21 October 1986, https://www.african-court.org/wpafc/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/AFRICAN-BANJUL-CHARTER-ON-HUMAN-AND-PEOPLES-RIGHTS.pdf.

[19] de Freitas & Myburgh (2011), p. 13-14.

[20] Kehrer, B.H., & Wolin, C.M. (1979). Impact of Income Maintenance on Low Birth Weight: Evidence from the Gary Experiment. The Journal of Human Resources, 14(4), 434–462, https://www.jstor.org/stable/145316.

[21] Moffitt, R.A. (1979). The Labor Supply Response in the Gary Experiment. The Journal of Human Resources, 14(4), 477-487, https://www.jstor.org/stable/145318.

[22] Hoynes, H., Miller, D., & Simon, D. (2015). Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(1), 172–211, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/pol.20120179.

[23] Dench, D., & Joyce, T. (2019). The Earned Income Tax Credit and Infant Health Revisited. Health Economics, 29(1), 72-84, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hec.3972.

[24] “How the Expanded 2021 Child Tax Credit Can Help Your Family,” IRS.gov, June 14, 2021, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/how-the-expanded-2021-child-tax-credit-can-help-your-family.

[25] Perez-Lopez, D. J. (2021). Economic hardship declined in households with children as child tax credit payments arrived. US Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, August 11, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/economic-hardship-declined-in-households-with-children-as-child-tax-credit-payments-arrived.html.

[26] Collyer, S., Curran, M., Davis, A., Harris, D., & Wimer, C. (2022). State child tax credits and child poverty: A 50-state analysis. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and the Center on Poverty and Social Policy. New York, NY: Columbia University, November, https://itep.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/Report-State-Child-Tax-Credits-and-Child-Poverty-A-50-State-Analysis-2022.pdf.

[27] Small, S., & Lancaster, D. 2022. Which New Jersey Households Received Child Tax Credit Payments and How Were They Spent? Center for Women and Work and New Jersey State Policy Lab. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University, https://rutgers.app.box.com/s/6gd7wv3r9zqdjmzwvr34qx7esndkqkse.

[28] “Who Qualifies for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC),” IRS.gov, accessed August 2, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/who-qualifies-for-the-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc.

[29] Strully, K. W., Rehkopf, D. H., & Xuan, Z. (2010). Effects of Prenatal Poverty on Infant Health: State Earned Income Tax Credits and Birth Weight. American Sociological Review, 75(4), 534–562, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0003122410374086.

[30] Markowitz, S., Komro, K.A., Livingston, M.D., Lenhart, O., & Wagenaar, A.C. (2017). Effects of state-level Earned Income Tax Credit laws in the U.S. on maternal health behaviors and infant health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine, 194, 67-75, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617306226?via%3Dihub#bib17.

[31] Komro, K.A., Markowitz, S., Livingston, M.D., & Wagenaar, A.C. (2019). Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity. Health Equity. Vol. 3, No. 1, https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/heq.2018.0061.

[32] “States and Local Governments with Earned Income Tax Credit,” IRS.gov, accessed August 2, 2024, https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/states-and-local-governments-with-earned-income-tax-credit.

[33] “Guidance Related to House Bill 481, Living Infants and Fairness Equality (LIFE) Act,” Department of Revenue, August 1, 2022, https://dor.georgia.gov/press-releases/2022-08-01/guidance-related-house-bill-481-living-infants-and-fairness-equality-life.

[34] H.B. 54 Tax Revisions, https://le.utah.gov/~2023/bills/static/HB0054.html.

[35] Schreiner, B. (2024). Kentucky Senate passes bill to grant the right to collect child support for unborn children. Associated Press, March 5, https://apnews.com/article/kentucky-legislature-child-support-pregnancy-41df8b7202e10fc3821d2df6a7ef5c4a.

[36] Hill, B., & Gurley-Calvez, T. (2019). Earned Income Tax Credits and Infant Health: A local EITC Investigation. National Tax Journal, 72(3), https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/epdf/10.17310/ntj.2019.3.06.

[37] “Child Tax Credit Enactments,” National Conference of State Legislatures, May 2, 2024, https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/child-tax-credit-enactments.

[38] Collyer et al. (2022). State child tax credits and child poverty: A 50-state analysis.

[39] “Child Tax Credit,” NJ Treasury: Division of Taxation, accessed August 6, 2024, https://nj.gov/treasury/taxation/individuals/childtaxcredit.shtml.

[40] “Colorado Child Tax Credit (CTC),” Colorado Department of Revenue: Taxation Division, accessed August 6, 2024, https://tax.colorado.gov/colorado-child-tax-credit.

[41] Patrick Titterton, “Vermont Child Tax Credit: A One-Year Lookback,” December 5, 2023, https://ljfo.vermont.gov/assets/Publications/Issue-Briefs/5d8e82f16c/GENERAL-372812-v1-CTC_Brief.pdf.

[42] HTRC/HB 163/a, https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/22%20Regular/final/HB0163.pdf.

[43] 2021 NY S 8009, https://custom.statenet.com/public/resources.cgi?id=ID:bill:NY2021000S8009&ciq=ncsl&client_md=2436db5e072a2f4402ee6b2e06d0926c&mode=current_text.

[44] “Empire State Child Credit,” New York State Department of Taxation and Finance, accessed August 6, 2024, https://www.tax.ny.gov/pit/credits/empire_state_child_credit.htm.

[45] Idaho Statute 63-3029L, https://legislature.idaho.gov/statutesrules/idstat/title63/t63ch30/sect63-3029l/.

[46] Sec. B-19. 36 MRSA §5219-SS, https://legislature.maine.gov/legis/bills/getPDF.asp?paper=SP0612&item=3&snum=128.

[47] “Healey-Driscoll Administration Celebrates Tax Cut Savings for Children and Families,” Mass.gov, October 5, 2023, https://www.mass.gov/news/healey-driscoll-administration-celebrates-tax-cut-savings-for-children-and-families.

[48] “2022 Child Tax Rebates,” State of Rhode Island Division of Taxation, Department of Revenue, accessed August 6, 2024, https://tax.ri.gov/guidance/special-programs/2022-child-tax-rebates.

[49] “2022 Child Tax Rebate,” Connecticut State Department of Revenue Services, accessed August 6, 2024, https://portal.ct.gov/drs/credit-programs/child-tax-rebate/overview.

[50] Davis, A., & Butkus, N. (2023). States are Boosting Economic Security with Child Tax Credits in 2023. Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, September 12, https://itep.org/states-are-boosting-economic-security-with-child-tax-credits-in-2023/.

[51] “Tax Credits, Deductions and Subtractions for Individual Taxpayers,” Comptroller of Maryland, accessed August 6, 2024, https://www.marylandtaxes.gov/tax-credits.php.

[52] “Arizona,” Tax Credits for Workers and Families, accessed August 6, 2024, https://www.taxcreditsforworkersandfamilies.org/state/arizona/.

[53] H.B. 153 Child Care Revisions, https://le.utah.gov/~2024/bills/static/HB0153.html.

[54] “Earned Income Tax Credit Campaign,” DISB, accessed August 2, 2024, https://disb.dc.gov/eitc.

[55] “Child Tax Credit Overview,” National Conference of State Legislatures, May 3, 2024, https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/child-tax-credit-overview.

[56] “The Uniform Illegitimacy Act and the Present Status of Illegitimate Children,” Columbia Law Review 24, no. 8 (December 1924): 909–15, https://doi.org/10.2307/1113644.

[57] Gump, D. (2020). The History of Prenatal Child Support in the United States. Human Defense Initiative. August 6, https://humandefense.com/the-history-of-prenatal-child-support-in-the-united-states/.

[58] “Lying-in Definition & Meaning,” Merriam-Webster, accessed August 2, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lying-in.

[59] Gump, D. (2020). The History of Prenatal Child Support in the United States.

[60] A collection of Pennsylvania laws spanning between 1700 and 1829. See: https://www.palrb.gov/Preservation/Smith-Laws#:~:text=These%20volumes%20contain%20certain%20public,not%20carried%20in%20Smith’s%20Laws.

[61] Gump, D. (2020). The History of Prenatal Child Support in the United States; Smith’s Laws, p. 29, https://www.palrb.gov/Preservation/Smith-Laws/View-Document/17001799/1705/0/act/0123.pdf.

[62] MacCoy, W.L. (1917). Law of Pennsylvania Relating to Illegitimacy. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 7(4), p. 514, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1473&context=jclc.

[63] Ibid., p. 519.

[64] Florida (1988). Acts of the Legislative Council of the Territory of Florida, v. 6 (1827-1828), p. 32-33, http://edocs.dlis.state.fl.us/fldocs/leg/actterritory/1827_1828.pdf.

[65] The Revised Statutes of the state of Wisconsin (1849), Chapter 31: Of the Support of Bastards, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89096048889&seq=263.

[66] Arkansas (1875). Arkansas Code Annotated, §9-10-110. “Judgment for lying in expenses.” Acts 1875 Adj Sess, ch. 24 §5.

[67] “Confinement Definition & Meaning,” Merriam-Webster, accessed August 2, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/confinement.

[68] Fay, J.D. (1874). Digest of the Laws of the State of New York, Vol. 1. “Bastards.” James Cockcroft & Company: New York.

[69] “An Act to amend Chapter 88 of the Revised Code of the State of Delaware, in relation to Illegitimate children,” 97th General Assembly (1921), https://legis.delaware.gov/SessionLaws/Chapter?id=41063.

[70] Green, L. C., Bobbitt, L. M., Evans, E., Ford, R. E., Gardner, W. C., Gravel, C. A., Matthews, Jr., W.L., Hamilton, D. A., Burdick, E. A., and Krause, H. D. (1973). “Uniform Parentage Act.” National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. Hyannis, Massachusetts: July 26-August 2, https://www.uniformlaws.org/viewdocument/final-act-with-comments-117?CommunityKey=10720858-ebe1-4e85-a275-40210e3f3f87&tab=librarydocuments.

[71] “The Uniform Illegitimacy Act and the Present Status of Illegitimate Children,” Columbia Law Review.

[72] California Penal Code § 270 – 273.75, https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displaySection.xhtml?lawCode=PEN§ionNum=270.

[73] Green et al. (1973). “Uniform Parentage Act.”

[74] Ibid., p. 18.

[75] Hawaii (1975). A Bill for an Act Relating to the Uniform Parentage Act. Act 66, H.B. No. 115, https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/slh/Years/SLH1975/SLH1975_Act66.pdf.

[76] Minnesota (1980). “The parentage act.” Session Laws 1980, c. 589. CHAPTER 589—S.F. No. 134, https://www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/1980/0/Session%2BLaw/Chapter/589/pdf/.

[77] Missouri (1986). Life begins at conception. Session Laws, Part III, Regular Session 2, B, https://revisor.mo.gov/main/OneSection.aspx?section=1.205&bid=65&hl=.

[78] “Uniform Parentage Act” (2002). National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. St. Augustine, Florida: July 28-August 4, 2000, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home/librarydocuments?LibraryKey=7bd3aca3-acc5-4e17-bccd-e8eceb818b11&5a583082-7c67-452b-9777-e4bdf7e1c729=eyJsaWJyYXJ5ZW50cnkiOiJjYWQ1ZmI1OC05NzUxLTQ1YzAtODFhZS02OGJhMjBiZDY0Y2YifQ%3D%3D.

[79] “Uniform Parentage Act” (2017). National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. San Diego, California: July 14-July 20, 2017, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home/librarydocuments?LibraryKey=7bd3aca3-acc5-4e17-bccd-e8eceb818b11&5a583082-7c67-452b-9777-e4bdf7e1c729=eyJsaWJyYXJ5ZW50cnkiOiJhY2U0NWQzOS04NWNmLTRkMzMtOTRmOC0wMThkMzcwMDgwMTIifQ%3D%3D.

[80] “2017 Parentage Act Map,” Uniform Law Commission, accessed August 6, 2024, https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=c4f37d2d-4d20-4be0-8256-22dd73af068f.

[81] Gump, D. (2020). The History of Prenatal Child Support in the United States.

[82] Utah Code 78B-12-105.1, https://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title78B/Chapter12/78B-12-S105.1.html?v=C78B-12-S105.1_2021050520210505#:~:text=Duty%20of%20biological%20father%20to%20share%20pregnancy%20expenses.,-(1)&text=Except%20as%20otherwise%20provided%20in,of%20the%20mother’s%20pregnancy%20expenses.

[83] 24 RS SB 110/GA, https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/recorddocuments/bill/24RS/sb110/bill.pdf.

[84] “Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996,” 110 STAT. 2230, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-104publ193/pdf/PLAW-104publ193.pdf.

[85] “Bucknell Institute for Public Policy Spring Survey,” Bucknell Blogs, accessed August 6, 2024, https://forthemedia.blogs.bucknell.edu/bucknell-institute-for-public-policy-spring-survey/.

[86] “Unborn Child Support Act,” https://www.hydesmith.senate.gov/sites/default/files/2022-07/Unborn%20Child%20Support%20Act.pdf.

[87] “Bicameral Legislation Would Allow Pregnant Mothers to Receive Child Support,” Cramer.sentate.gov, January 18, 2024, https://www.cramer.senate.gov/news/press-releases/bicameral-legislation-would-allow-pregnant-mothers-to-receive-child-support.