Midtrimester Abortion Epidemiology, Indications and Mortality

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this paper mistakenly said that AGI estimated a total of 1.6 million abortions as the denominator for the rate of abortion-related mortality between 1998-2010. This has since been corrected to “16.1 million.”

By Monique Chireau Wubbenhorst, M.D., M.P.H., F.A.C.O.G., F.A.H.A

This is Issue 5 of the On Science series.

Introduction. This paper will address epidemiology, complications, indications, procedures and protocols, and women’s reasons for undergoing second trimester induced abortion.

Terminology. CDC notes that “For the purposes of surveillance, a legal induced abortion is defined as an intervention performed by a licensed clinician (e.g., a physician, nurse-midwife, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) within the limits of state regulations that is intended to terminate a suspected or known ongoing intrauterine pregnancy and that does not result in a live birth” [emphasis added]. Thus, the intent of any abortion is the death of the unborn child at any gestational age. In contrast, procedures performed before the fetus is capable of surviving separation which are done in order to save the life of the mother (for example for severe hypertension and other diseases) may be more correctly referred to as non-abortive terminations of pregnancy or preterm parturitions, since the goal of the procedure is not to kill the fetus, but to end pregnancy for the preservation of the life of the mother, and to save her unborn child if at all possible.

Epidemiology. Statistics suggest that approximately 619,591 – 888,000 abortions were performed in the United States in 2018 based on state-level and CDC data. Of these, 85.2% were performed in unmarried women. Approximately 39,979 abortions, or 7.8 % of all abortions were performed at > 14 weeks’ gestation. While many more abortions are performed in the first trimester than the second trimester, most abortion-related adverse outcomes occur in second trimester or later abortions (Grimes 1985; Bartlett et al 2004; Lohr et al 2010). That is, morbidity, and mortality from abortion tend to cluster in second and third trimester procedures.

The percent of second trimester abortions in the U.S. has fluctuated over the last 40-45 years (CDC and Alan Guttmacher Institute [AGI] data). For example, Epner et al (1998), using 1992 AGI data, examined the distribution of types of abortion by numbers, gestational age and race/ethnicity. They found that 11% of a total of 1,528,930 abortions, or 170,550 procedures were performed at or after 13 weeks’ with 1% of abortions being performed at > 21 weeks’ gestation. CDC data from the same year corroborates this, noting that 11.5% of abortions were performed at > 13 weeks’ gestation, with 1.5% of abortions performed at or after 21 weeks’ gestation. CDC’s 2018 abortion surveillance, which, as in other years, is limited by the number of States not reporting, notes that in 2009, 8.2 % of a total of 519,164, or 42,571 abortions were performed in the second trimester. In 2018, 8.5% of 395,960 abortions or 33,657 abortions were performed in the second trimester.

Epner’s study also describes the number of late second trimester abortions performed at greater than 21 weeks’ gestation. Of the 16,450 abortions done at greater than or equal to 21 weeks’ in 1998, 63% were done at 21-22 weeks’ gestation, 30% at 23-24 weeks’, 5% at 25-26 weeks’ and 2% at >26 weeks’. For comparison, contemporaneous CDC data indicated that 1.2% of all abortions were performed after 21 weeks’ gestation.

Most second trimester abortions are performed in women who are 20-29 years old. At every gestational age band from 14 to > 21 weeks’ gestation, the 20-29 year old group has the largest number of abortions, followed by the 30-34 year old group.

Racial disparities. Though African Americans constitute only 13-14% of the U.S. population, 33% of all abortions occur in African American women, based on CDC’s 2018 abortion surveillance (this sampling frame does not include data from California, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and Wyoming). Black women have higher abortion rates than any other race/ethnicity. The abortion rate is the number of abortions per 1000 women of the same ethnicity. For African American women it is 21.2 per 1000, vs. 6.2 for European American women, 11.9 for women of Other ancestry, and 10.9 for Hispanic women. Black women also have higher abortion ratios than any other race/ethnicity. The abortion ratio is the number of abortions per 1000 live births in a given population. For black women it is 335, vs. 110 for white women, 213 for women of other ancestry and 158 for Hispanic women. Put differently, for every 1000 live births among African American women, the abortion ratio indicates that roughly one-third fewer African American infants are born annually than would have been born otherwise (excluding those not born alive due to miscarriage and stillbirth). These statistics likely underestimate abortion rates and ratios and hence the impact of abortion on the African American population, given that data from states with large populations are not included in the CDC dataset.

38.6% of second trimester abortions are performed in Black women. The below chart shows that in the second trimester, at every gestational age band up to 21 weeks’ gestation, more abortions are performed in African American women than any other ethnicity. Because 22 reporting areas were excluded in this sampling frame (including states with large populations such as California and New York) it is highly likely that these numbers underestimate the number of second trimester abortions in African American women, the short- and long-term impact of abortion on the health of African American women, and the magnitude of the racial disparity in second trimester abortion between African American women and women of other ethnicities.

Table 1. Number and percent of abortions, by gestational age and ethnicity, adapted from CDC abortion surveillance, 2018*, at Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2018 | MMWR (cdc.gov)†

|

Ethnicity |

14-16 weeks’ |

16-18 weeks’ |

18-20 weeks’ |

>21 weeks’ |

Total |

|

White |

3796 (34.1) |

2297 (35) |

2214 (37.6) |

1128 (41.7) |

9435 (36) |

|

Black |

4481 (40.3) |

2635 (40.4) |

2215 (37.7) |

781 (28.9) |

10,112 (38.6) |

|

Other |

888 (8) |

454 (6.9) |

473 (8.0) |

315 (11.6) |

2130 (8.1) |

|

Hispanic |

1948 (17.5) |

1127 (17.3) |

980 (16.6) |

477 (17.6) |

4532 (17.2) |

|

TOTAL |

11,113 |

6513 |

5882 |

2701 |

26,209 |

* Per CDC, “Data from 30 reporting areas; excludes data from 22 reporting areas including California, Colorado, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York City, New York State, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and Wyoming”.

†These numbers were derived using the number of abortions performed at or after 14 weeks’ gestation as the denominator rather than the sum of all abortions.

Abortion methods. Abortions in the second trimester are performed using medical or surgical protocols. In the United States 96.9% of abortions at > 13 weeks’ gestation are performed surgically using dilation and evacuation (D&E), suction procedures, and hysterotomy (incision into the uterus) or hysterectomy (removal of the uterus). The latter 2 procedures are more likely to be used when other abortion procedures have failed or when complications ensue. Intact dilation and extraction (D&X) has also been used in the past.

Per CDC data, approximately 3.1% of abortions in the second trimester are performed using medical methods, mostly with prostaglandins administered orally or vaginally with or without mifepristone to induce labor. The process of labor usually but not always results in the death of the unborn child. A small percentage of medical abortions are still being performed by instillation (injection) of prostaglandins, saline or urea into the amniotic cavity, especially in the late second trimester and third trimester. Instillation protocols were formerly used more commonly than at present and are “both less common and not recommended” (Lerma et al, 2020) since they are associated with increased risk for maternal adverse outcomes. Instillation procedures used in the late second trimester and early third trimester induce labor and usually but not always kill the fetus, and may result in the birth of a living premature infant. Despite the markedly increased risks for complications and death associated with these procedures, CDC data from a limited number of states indicate that in 2018, an estimated 219 out of 556,294 or 0.0394% of abortions for which there were data on method used, used instillation procedures. Only Arizona (112 cases), Massachusetts (8 cases) and New York (72 cases) reported the use of instillation procedures. Again, because data were not included from California, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Wyoming, this dataset likely underestimates the number of instillation abortions being performed.

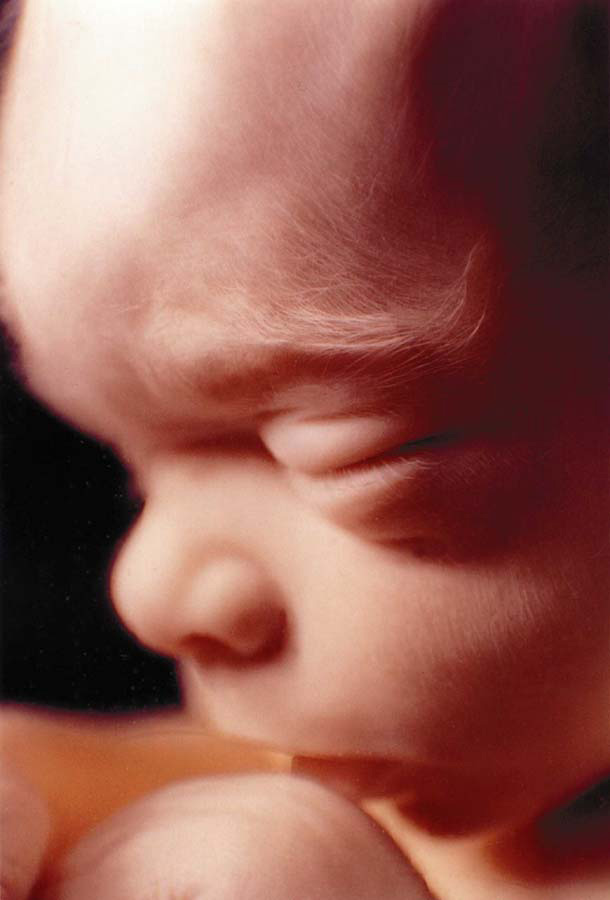

D&E is carried out by dilating the uterine cervix using dilators or medications, then using instruments to grasp, crush, pull apart and remove the unborn child in pieces, causing fetal death in the process. Formerly the D&X procedure was used, and involved dilating the uterine cervix, rotating the fetus to a foot-down position, pulling him or her out by the feet to the level of the head, and then using instruments to cut open or crush the skull and suction out the brain to facilitate delivery of the head. D&X on a living fetus is banned in the United States, and feticide (lethal injection of medications into the fetal heart, amniotic sac or umbilical cord to cause death) is required prior to the procedure if D&X is to be used. Many abortionists use feticide prior to second trimester D&E as well to ensure that the aborted fetus does not show signs of life, and also because it is thought that feticide may result in maceration (softening of the fetal skull and tissues) thus facilitating abortion.

Beginning in the 1980s, D&E became increasingly popular, even though to date there are no large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of this method, or comparing it to contemporary abortion methods. Such trials are the gold standard for assessing the safety and efficacy of any procedure, especially in comparison to other procedures. A 2010 Cochrane Systematic Review of the medical literature on D&E noted 2 RCTs suitable for review. One compared D&E with intra-amniotic infusion of prostaglandin F2-alpha (Grimes et al, 1980). This trial enrolled a total of 94 patients and showed that D&E was safer and faster than instillation of prostaglandin F2-alpha. But, as noted above, the latter procedure is very rarely if ever used at present. The second trial randomized patients to D&E or labor induction with mifepristone-misoprostol. However, this study enrolled only 18 patients (9 patients randomized to D&E and 9 to labor induction). In the absence of data from large well-designed RCTs, numerous observational and retrospective studies have attempted to compare D&E with more current abortion protocols.

Complications (mortality). The risk of death from abortion increases with gestational age, and as Turok et al (2008) note, “these procedures are potentially more morbid because of the increased size of fetal and placental tissue, increased blood volumes and a distended uterus…”. Cates and Grimes (1981) used data from approximately 243,000 D&E procedures from 1972-1978 and noted that for women undergoing D&E the mortality rate was 5.6 per 100,000 at 13-15 weeks’ gestation and 14.0 per 100,000 at > 16 weeks’. In comparison, the mortality rate for dilation and curettage procedures at < 12 weeks’ was 1 per 100,000; for instillation procedures at > 13 weeks’ it was 13.9 per 100,000 for saline and 9 per 100,000 for prostaglandin and other agents; and for hysterectomy and hysterotomy 42.8 per 100,000. The authors note that “because the risk of death from D&E is directly related to gestational age, the death:case rate [or ratio of deaths per 100,00 procedures] in the 13-15 week interval (5.6/100,000) is significantly…less than at 16 weeks’ or later (14/100,000). Thus, the lower risk of dying from D&E compared with instillation techniques appears primarily related to the comparative advantages of D&E in the 13-15 week period. After 15 weeks’ gestation, the death:case rates for D&E and instillation agents are quite similar…”.

Epner et al (1998) described second trimester abortion maternal mortality between 1974-1987 for 1,931,673 second trimester procedures and noted that with D&E, 2 per 100,000, 6.5 per 100,000 and 11.9 per 100,000 women who underwent abortion at 13-15 weeks’, 16-20 weeks’ and > 21 weeks’ gestation respectively, died as a result of the procedure. The authors also noted that “At 21 weeks or more, the mortality rate was 16.7 per 100,000 procedures and exceeded the risk of maternal death from childbirth, though the difference was not statistically significant”.

Bartlett et al (2004) examined risk factors for abortion related mortality from 1988 – 1997 using CDC data. Their study showed a decline in overall abortion-related mortality over the study period as well as a decline in numbers of instillation procedures, from 10% in 1972 to 3% in 1980. They also found that mortality rates for second trimester procedures (not stratified by procedure type) were 1.7 per 100,000 at 13-15 weeks’ gestation, 3.4 per 100,000 at 16-20 weeks’, and 8.9 per 100,000 at > 21 weeks’. Mortality rates for D&E were 2.5 times lower than for other procedures such as instillation, though these differences were not significant and the analysis was limited by small numbers of cases for some procedures, and availability of specific data.

Studies have quantified the association between increasing gestational age and increasing risk for maternal mortality with second trimester abortion. In the above study by Cates and Grimes, D&E procedures performed at 16 weeks’ gestation or later were nearly 3 times more dangerous than those performed at 13-15 weeks’ gestation. The risk of a woman dying from second trimester abortion increased 50% for each additional week of gestation.

Similarly, Bartlett et al found that “the risk of death increased exponentially with increasing gestational age.” According to their statistical model, “there is a 38% increase in risk of death for each additional week of gestation…currently, the risk of death increases exponentially at all gestational ages, whereas for women obtaining abortions in the earlier time period (1970-1979), the risk of death increased with increasing gestational age but leveled off at the highest gestational ages…the risk of death at later gestational ages may be less amenable to reduction because of the inherently greater technical complexity of later abortions related to the anatomical and physiologic changes that occur as pregnancy advances”. Other factors may play a role as well.

Zane et al (2015) studied abortion-related mortality from 1998-2010 using CDC and AGI data. The latter estimated a total of 16.1 million abortions as the denominator in this time period, while CDC data estimated a total of 7,917,600 abortions as the denominator. From 1998-2010 an estimated 108 women died following abortion, 21 women after abortions performed between 14 and 17 weeks’ gestation, and 36 women after abortions performed at > 18 weeks’. The authors applied an estimation method to AGI data using CDC gestational age distributions since the AGI data (Jones and Jerman, 2014) did not report abortion data by gestational age. The authors found that the mortality rate for women undergoing second trimester abortion increased with gestational age, from 2.4 deaths per 100,000 abortions at 14-17 weeks’ gestation to 6.7 deaths per 100,000 abortions at > 18 weeks’ gestation.

Racial-ethnic disparities in second trimester abortion mortality rates indicate that the procedure is markedly more dangerous for African American than for European American women. Cates and Grimes noted that for D&E procedures performed in the second trimester, “Women of black and other nonwhite races had death:case rates 3 times higher than those of white women. Moreover, controlling for gestational age widened this apparent difference between the 2 racial groups”. The apparent “benefit” of lower mortality from D&E performed at earlier gestational ages was not experienced by African American women, and the difference in mortality rates “between white and nonwhite women was greater at 13-15 weeks’ than at later gestational ages”. Bartlett et al found that “The second most significant risk factor for death [from abortion, after gestational age] overall was race. Women of black and other races were 2.4 times as likely as white women to die of complications of abortion…At all gestational ages, women of black and other races had higher case mortality rates than white women”. Finding that “women of black and other races tend to have abortions at later gestational ages”, the authors used statistical methods to account for this difference and found that women of African American and other races-ethnicities were still twice as likely as European American women to die from abortion at any gestational age. This race-ethnicity specific risk is superimposed on the already increased risk of second trimester abortion procedures. Despite changes in abortion protocols and techniques noted by the authors, including routine use of ultrasound to assess gestational age and improved dilation methods (Cates and Grimes), and a decline in the use of instillation protocols from 10% in 1972 to 3% in 1980 (Bartlett et al), the racial-ethnic disparity in mortality persisted over the 23-year interval between the 2 studies. Zane et al also reported that the abortion “mortality rate was 0.4 for non-Hispanic white women, 0.5 for Hispanic women, 1.1 for black women and 0.7 for women of all other races…Black women have a risk of abortion-related death that is three times greater than that for white women”.

The reasons for this disturbing racial-ethnic disparity in mortality are not clear. African American women are more likely to be overweight or obese, and in selected populations, to have higher risk for chronic disease, but studies examining the impact of obesity on abortion-related morbidity and mortality have yielded conflicting results. Some studies show increased risk with increasing body mass index (BMI), and others show no increased risk (Murphy et al, 2012; Lederle 2015). A contemporary study by Mark et al (2018) found that second trimester abortion complications (hemorrhage, need for repeat procedure, uterine perforation, cervical laceration, medication reaction, unexpected surgery or unplanned hospital admission) increased with increasing BMI, from 1.6% for normal weight women to 3.2% for overweight women, 3.4% for BMI = 30-34.9, 6.4% for BMI = 35-39.9, and 8.7% for BMI > 40. The odds ratio for complications in women with BMI > 40 compared with normal weight women was 5.9 (95% CI 1.93-8.07; p < 0.01). Because of limitations in follow up the authors suggested that complication rates may have been underestimated.

There is a need for better understanding of the factors contributing to the racial-ethnic disparity in second trimester abortion-related mortality for African American women. Dehlendorf et al (2013) suggested a number of possible contributing factors, though most were related to contraceptive use rather than to abortion per se. In any event, the higher rates of procedure-related mortality from second trimester abortion coupled with higher rates of second trimester abortion indicate that African American women are disproportionately exposed to procedure-related mortality from second trimester abortion.

Complications (morbidity). Multiple observational and retrospective studies have evaluated complications associated with second trimester abortion. For example, Turok et al (2007) studied differences in complications between second trimester abortions performed in 475 women, in hospitals vs. free-standing clinics. The authors found that major complications (defined as death, uterine perforation, hysterectomy, transfusion, clotting disorders, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, stroke or heart attack, need for exploratory surgery, and prolonged hospitalization) occurred in 11% of hospital D&E patients, 10% of hospital induction patients, and 1% of clinic patients (though there were no deaths in study patients). Other complications included:

- Need for readmission (24% in the hospital D&E group, 1% in the clinic D&E group, and 16% in the hospital induction group);

- Need for curettage after abortion for retained placenta and/or fetal parts (0% in the hospital D&E group, 1% in the clinic D&E group, and 28% in the hospital induction group);

- Infection of the fetal membranes after initiation of the procedure (1% in the hospital D&E group, 0% in the clinic D&E group, and 6% in the hospital induction group); and

- Uterine infection (1% in the hospital D&E group, 4% in the clinic D&E group, and 5% in the hospital induction group).

Of note, the patients undergoing abortion or pregnancy termination in-hospital had more medical problems, were further along in pregnancy (higher gestational ages) and were more likely to be undergoing non-abortive pregnancy termination for fetal death in utero than those seen in the clinic. The authors also note that complications may have been underreported due to loss to follow-up.

Edlow et al (2011) noted that “[higher] gestational age was significantly associated with maternal morbidity”, with women undergoing abortion at > 20 weeks’ being 2 ½ times more likely to suffer a complication than women undergoing abortion at < 20 weeks’. Also, similar to the association between increasing mortality with increasing gestational age noted by Bartlett et al, Lederle et al found a 30% increased risk for complications with each additional week of gestation.

Table 2. Complications associated with second trimester abortion (medical and surgical)

| Complication | Incidence and estimated cases per year* | Studies |

| Bleeding and hemorrhage† | 0.09-11.6%

(35-4637) |

Peterson 1983, Altman 1985, Autry 2002, Jacot 1993, Ashok 2004, Castleman 2006, Patel 2006, Mentula 2011, Lederle 2016, Sonalkar et al 2017 |

| Infection† | 1.3-3%

(520-1199) |

Peterson 1983, Altman 1985, Jacot 1993, Autry 2002, Ashok 2004, Patel 2006, Castleman 2006, Mentula 2011 |

| Uterine perforation | 0.45-3.7%

(180-1479) |

Peterson 1983, Grimes 1984, Altman 1985, Jacot 1993, Pridmore and Chambers 1999, Ashok 2004, Patel 2006, Castleman 2006, Nucatola 2008 |

| Uterine rupture | 0-4.8%

(0-1919) |

Peterson 1983, Altman 1985, Jacot 1993, Herabutya 2003, Ashok 2004, Dashalakis 2005, Dickinson 2005, Castleman 2006, Daponte 2006, Mazouni 2006, Patel 2006, Cayrac 2011 |

| Cervical laceration | 1.3-3.8%

(520-1519) |

Peterson 1983, Altman 1985, Jacot 1993, Autry 2002, Ashok 2004, Castleman 2006, Patel 2006, Lederle 2016 |

| Embolus

Pulmonary embolus

Amniotic fluid embolus‡ |

0.1-0.2% (39-800)

0.000125 -0.001% (<1-<1)

|

ACOG Practice Bulletin #135, 2013 |

| Coagulopathy | 0.17-0.2

(67-80) |

York 2012, Frick 2010, Lederle 2016 |

| Exploratory surgery

Repair of bowel injury

Hysterectomy |

0.53% (2119)

0.00005-2.4% (<1-959) |

Darney 1990

Mentula 2011, Garofalo 2017 |

| Retained fetal parts and/or placenta requiring D&C | 0.2-21%

(80-8396) |

Autry 2002, Mentula 2011, Lederle 2016, Peterson 1983, Jacot 1993 Ashok 2004, Altman 1985, Patel 2006, Castleman 2006 |

*Based on denominator of 39,979 second trimester abortions from CDC 2018 abortion surveillance.

†The most common causes of abortion related mortality in the second trimester are hemorrhage and infection (Zane et al, 2015)

‡Mortality rate for amniotic fluid embolism after second trimester abortion is 80% (ACOG Practice Bulletin #135, 2013)

While many studies have described short-term or immediate complications of abortion, such adverse outcomes as repeat curettage for retained placenta or fetal parts, infection and hysterectomy have long-term significance. Repeat curettage is a risk factor for damage to the uterine lining, which may be associated with infertility or abnormal placental attachment in future pregnancies. Uterine infections following abortion are of concern due to a possible effect on future fertility, and it is readily apparent that hysterectomy results in irreversible loss of fertility.

Temporal changes in the incidence of second trimester abortion complications may occur due to increasing rates of cesarean delivery. A previous study by Ben-Ami et al (2009) did not find an increased risk for complications in women with a history of cesarean delivery. Frick et al (2010) in contrast, found that women with a history of > 1 cesarean delivery had 7 times the risk for major complications compared with those who had no history of cesarean delivery.

Finally, most discussions of second trimester morbidity focus appropriately on complications suffered by the patient. However, Grossman et al (2008) noted that “any discussion of which method [of second trimester abortion] to offer and which is considered to be preferable needs to take into account not only the safety and efficacy of the procedure but also the experience of the abortion…Proponents of surgical abortion have long argued that D&E is far more efficacious, faster and…spares women having to endure labour and the delivery of a bruised, dead fetus…Conversely, D&E is exceedingly predictable with respect to the amount of time required”. In contrast to medical abortion, the authors note that “D&E requires total physician involvement, and as gestational age increases, much of the emotional burden of the procedure is borne by the physician…some practitioners feel it very distressing to perform this procedure at advanced gestations. However, it may also be true that some nurses attending the delivery of a fetus after medical induction in mid-trimester abortion find it equally difficult.”

Similarly, Benditt (1979) added that following medical abortion, “in the end, she [the patient] and the nurse are confronted by a fetus closely resembling a premature infant…In D&E, on the other hand, much more responsibility is shifted to the physician…The woman never sees the fetus. The physician, on the other hand, is faced with the difficult task of crushing ossified fetal parts, and reconstructing fetal sections to make sure the uterus has been completely evacuated”. It is important to keep in mind the difficulty of the abortion experience for the mother, and also for the nurse and/or physician attending her.

Indications. The number and percent of second trimester abortion procedures, and to some extent the procedure used, vary according to the reason for the abortion (the indication). Fetal indications include:

- Fetal anomalies such as an abnormal number of chromosomes (for example, Down syndrome), neural tube defects (for example spina bifida), cardiac defects, and other prenatally diagnosed abnormalities. Abortions performed due to diagnosis of a fetal anomaly have been referred to as eugenic terminations of pregnancy because their goal is to prevent the birth of an affected newborn and hence an individual with disabilities, especially those which are heritable.

- Maternal indications include (a) Medical conditions for which ongoing pregnancy poses a threat to the life of the mother, for example uterine infection, in utero fetal death, and diseases such as severe hypertension or kidney failure; (b) Rape or incest; (c) Mental health conditions; and (d) Social reasons.

Most second trimester abortions are performed when a healthy woman has a normal fetus and desires to end her pregnancy. Data on reasons given by women for abortion are not available from CDC due to reporting constraints. A number of States, however, collect these data (see Table 1 below). Relatively few second trimester abortions are performed for the health of the mother (highest percentage 7.1% among States reporting) or fetal anomalies (highest percentage 2.3% among States reporting). Because of different sampling methods and denominators, comparisons between states are likely to not be valid.

TABLE 3. Reasons for abortion by State, 2019

|

State, number of abortions performed in 2019 |

Reasons given by women, or indications for abortion | ||

|

Fetal anomaly (number, %) |

Mother’s physical health (number, %) |

Sexual assault (rape and incest), (number,%) |

|

| Arizona (13,093) | 171 (1.3) | 181 (1.4) | 30 (0.00041) |

| Florida (71,194) | 700 (0.98) | 194 (0.27) | 109 (0.15) |

| Minnesota (9922) | 183 (1.8) | 713 (7.1) | 96 (0.97) |

| Louisiana (8144) | 70 (0.86) | 252 (3%) | 49 (0.6) |

| Nebraska (2068) | 15 (0.7) | 82 (4%) | 7 (0.3) |

| Oklahoma (4995) | 16 (0.3) | 22 (0.4) | Suppressed for confidentiality |

| South Dakota (414) | Not ascertained | 15 (3.6) | 8 (1.9) |

| Utah (2895) | 67 (2.3) | 6 (0.2) | 5(0.17) |

The decision to undergo abortion of an unborn child diagnosed with anatomic or chromosomal abnormalities is an agonizing one for parents. Very often, a diagnosis of fetal abnormality comes as a shock later in gestation. At the time of diagnosis of an abnormality, the pregnancy is already apparent to others, and parents can be overwhelmed by the process (see, for example https://jezebel.com/later-abortion-a-love-story-1832631748). There are, however, some important nuances related to testing, counseling and the problem of false-positive diagnoses, that is, a diagnosis based on a test result that is interpreted as positive but in fact is negative.

Screening for possible fetal abnormalities occurs in both the first and second trimesters. Positive screening for chromosomal abnormalities may be confirmed using chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis, both of which carry risks including bleeding, miscarriage and false-positive results. The latter can occur due to placental or somatic mosaicism. Diagnostic ultrasound testing for fetal anomalies is typically performed in the second trimester. As a result, the diagnosis of fetal abnormalities and the higher complication rate associated with second trimester abortion (especially late second trimester abortion) begin to impinge upon questions of viability.

Edling et al (2021) for example, noted that the increasing complexity of prenatal diagnostic technology, and the time required to complete and disclose it, pose challenges for both clinicians and parents. The authors point out that “[d]ue to advances in neonatal medicine, fetal viability and the upper limit of late induced abortions have been converging over the last few decades”. They note that in Sweden, abortion is readily available up to 18 weeks’ and “two-thirds of the yearly 400-500 induced abortions after gestational week (gw) 18 are due to fetal anomalies”, while acknowledging that “second trimester induced abortions are associated with more complications compared with first trimester abortions”. In Sweden, if a pregnancy is past 18 weeks’ gestation, permission must be obtained from the national ethics committee for an abortion, because “The upper time limit of induced abortion is the presumed viability of the fetus outside the uterus…intensive neonatal care is offered in Sweden from gw 22+0, which is now considered the limit of viability in clinical practice…both applications and permission are extremely rare””. The authors’ study focused on how to expedite the process of parents’ decision-making to “minimize terminations approaching the legal limit”, in order to attempt to reconcile the “conflicting demands” of needing to establish a diagnosis and give parents time and information to make a decision. But it is difficult to prescribe how much time a couple needs to process information about anomalies in their unborn child and arrive at a decision. Moreover, the possible option of in utero surgical or medical therapy or perinatal hospice may change this decision-making process.

Another nuance in fetal diagnostics relates to the fact that prenatal diagnosis is by definition presumptive. That is, until postmortem examination of the aborted fetus has been carried out, the prenatal diagnosis cannot be confirmed. Confirmation of a diagnosis of fetal abnormality is mandatory to identify false-positive cases and to attempt to reduce or eliminate their occurrence. Situations where an erroneous prenatal diagnosis results in abortion of a normal child are devastating to parents (see, for example, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/23/irish-couple-to-receive-damages-over-advice-that-led-to-unnecessary-abortion). As a quality measure, pathologists have studied whether the fragmentation of the fetal body caused by D&E hinders confirmatory postmortem examination. Struksnaes et al (2016) carried out a study correlating fetal ultrasound and autopsy findings in 1029 aborted fetuses. They noted a 1.3% false-positive rate and emphasized that “fetal autopsy remains a quality control of ultrasound findings resulting in TOP”.

Boecking et al (2017) studied 448 fetuses aborted by D&E. They found that for 89 pregnancies, a decision was made to abort the unborn child due to ultrasound diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities. In 86% of these, postmortem correlation was prevented by fragmentation of brain tissue and spinal cord structures, including “all 110 intracerebral abnormalities”. For congenital cardiac defects, 21% of abnormalities could not be confirmed, and 51% of specimens were too fragmented to confirm a diagnosis. For trisomy 21, a chromosome abnormality, 18% of fetuses examined had no abnormal findings, suggesting that the prenatal diagnosis may have been incorrect. The only other means of verifying such chromosomal abnormalities would be to karyotype (perform chromosome analysis) on the aborted fetus. Pavlicek et al, in contrast, observed 100% correlation between fetal ultrasound and autopsy in 243 aborted fetuses.

Multiple studies have examined women’s reasons for delaying a decision to end their pregnancy into the second trimester. These include conflict about abortion, discovery of a fetal abnormality, inability to access first trimester abortion, and social reasons. The most common reason given by women who end their pregnancies in the second trimester is not wanting to have a child at the time of pregnancy. The decision-making process related to second trimester abortion is complex, however as noted in recent studies (Drey 2006, Ingham 2008). Ingham et al in particular noted that in their study of “reasons for delay in seeking or obtaining abortion” among 883 women, “No clear, single reason emerges”.

In conclusion, most second trimester abortions are performed in healthy women and end the lives of healthy fetuses. Women undergoing second trimester abortion are at risk for significant morbidity and mortality, which increase with gestational age at abortion, but the magnitude of this risk cannot be accurately quantified due to severe limitations in the quality, consistency and completeness of state- and national-level abortion data. There is an urgent need for an improved policy focus on this issue.

During the second trimester, at every gestational age up to 21 weeks, more abortions are performed in African American women than any other ethnicity. They are thus more likely to be exposed to the risks and adverse outcomes of second trimester abortion. African American women are also two to three times more likely to die from abortion. The impact of abortion on maternal morbidity and mortality, fetal mortality and population health in African Americans is considerable, without any apparent benefit proportional to the disparities in risk and outcomes. Women must be adequately counseled about second trimester abortion’s risks, and every effort made to avoid abortion and its negative outcomes – both for the women undergoing it, and for clinicians attending them. The needs of women, particularly African American women, confronted with a pregnancy about which they may have conflicting intentions and desires, and other concerns, should be addressed in ways that help protect, support and nurture both mother and child.

Monique Chireau Wubbenhorst, M.D., M.P.H., F.A.C.O.G., F.A.H.A is a board-certified obstetrician-gynecologist with over 20 years’ experience in patient care, teaching, research, health policy, public health, global health and bioethics. Dr. Wubbenhorst’s clinical career has focused on caring for women in underserved and disadvantaged populations, especially African American and Native American communities, with a focus on women with medical, social and psychiatric comorbidities. She is a guest contributor to the Charlotte Lozier Institute.

Bibliography

- Aksel S, Lang L, Steinauer JE, et al. Safety of Deep Sedation Without Intubation for Second-Trimester Dilation and Evacuation. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):171-178. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002692.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Second-Trimester Abortions. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 135. 2013. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2013/06/second-trimester-abortion

- Baardman ME, du Marchie Sarvaas GJ, de Walle HE, et al. Impact of introduction of 20-week ultrasound scan on prevalence and fetal and neonatal outcomes in cases of selected severe congenital heart defects in The Netherlands. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;44(1):58-63. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.13269.

- Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, et al. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):729-737. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000116260.81570.60.

- Ben-Ami I, Schneider D, Svirsky R, Smorgick N, Pansky M, Halperin R. Safety of late second-trimester pregnancy termination by laminaria dilatation and evacuation in patients with previous multiple cesarean sections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):154.e1-154.e1545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.029.

- Benditt, John. “Second-Trimester Abortion in the United States.” Family Planning Perspectives 11, no. 6 (1979): 358–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2134220.

- Boecking CA, Drey EA, Kerns JL, Finkbeiner WE. Correlation of Prenatal Diagnosis and Pathology Findings Following Dilation and Evacuation for Fetal Anomalies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017;141(2):267-273. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2016-0029-oa.

- Bryant AG, Grimes DA, Garrett JM, Stuart GS. Second-trimester abortion for fetal anomalies or fetal death: labor induction compared with dilation and evacuation. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):788-792. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31820c3d26.

- Burr WA, Schulz KF. Delayed Abortion in an Area of Easy Accessibility. JAMA. 1980;244(1):44–48. doi:10.1001/jama.1980.03310010030023

- Bygdeman, Marc, and Kristina Gemzell-Danielsson. “An Historical Overview of Second Trimester Abortion Methods.” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 31 (2008): 196–204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475418.

- Castleman LD, Oanh KT, Hyman AG, Thuy le T, Blumenthal PD. Introduction of the dilation and evacuation procedure for second-trimester abortion in Vietnam using manual vacuum aspiration and buccal misoprostol. Contraception. 2006;74(3):272-276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.021.

- Cates W Jr, Grimes DA. Deaths from second trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation: causes, prevention, facilities. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58(4):401-408.

- Cayrac M, Faillie JL, Flandrin A, Boulot P. Second- and third-trimester management of medical termination of pregnancy and fetal death in utero after prior caesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;157(2):145-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.03.013.

- Chasen ST, Kalish RB, Gupta M, Kaufman JE, Rashbaum WK, Chervenak FA. Dilation and evacuation at >or=20 weeks: Comparison of operative techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1180-1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.034.

- Crane JP, LeFevre ML, Winborn RC, et al. A randomized trial of prenatal ultrasonographic screening: impact on the detection, management, and outcome of anomalous fetuses. The RADIUS Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171(2):392-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70040-0.

- Daponte A, Nzewenga G, Dimopoulos KD, Guidozzi F. The use of vaginal misoprostol for second-trimester pregnancy termination in women with previous single cesarean section. Contraception. 2006;74(4):324-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.023.

- Darney PD, Atkinson E, Hirabayashi K. Uterine perforation during second-trimester abortion by cervical dilation and instrumental extraction: a review of 15 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75(3 Pt 1):441-444.

- Daskalakis GJ, Mesogitis SA, Papantoniou NE, Moulopoulos GG, Papapanagiotou AA, Antsaklis AJ. Misoprostol for second trimester pregnancy termination in women with prior caesarean section. BJOG. 2005;112(1):97-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00285.x.

- Dehlendorf C, Harris LH, Weitz TA. Disparities in abortion rates: a public health approach. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):1772-1779. https://dx.doi.org/10.2105%2FAJPH.2013.301339.

- Dickinson JE. Misoprostol for second-trimester pregnancy termination in women with a prior cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):352-356. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aog.0000151996.16422.88.

- Edling, A, Lindström, L, Bergman, E. Second trimester induced abortions due to fetal anomalies—a population-based study of diagnoses, examinations and clinical management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021; 00: 1– 7. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14230.

- Edlow AG, Hou MY, Maurer R, Benson C, Delli-Bovi L, Goldberg AB. Uterine evacuation for second-trimester fetal death and maternal morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):307-316. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3182051519.

- Epner JE, Jonas HS, Seckinger DL. Late-term abortion. JAMA. 1998;280(8):724-729. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.8.724.

- Fontenot Ferriss AN, Weisenthal L, Sheeder J, Teal SB, Tocce K. Risk of hemorrhage during surgical evacuation for second-trimester intrauterine fetal demise. Contraception. 2016;94(5):496-498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.06.008.

- Frick AC, Drey EA, Diedrich JT, Steinauer JE. Effect of prior cesarean delivery on risk of second-trimester surgical abortion complications. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):760-764. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e3181d43f42.

- Goyal V. Uterine rupture in second-trimester misoprostol-induced abortion after cesarean delivery: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(5):1117-1123. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e31819dbfe2.

- Grech V. Evidence of socio-economic stress and female foeticide in racial disparities in the gender ratio at birth in the United States (1995-2014). Early Hum Dev. 2017;106-107:63-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.02.003.

- Grimes, David A. “The Choice of Second Trimester Abortion Method: Evolution, Evidence and Ethics.” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 31 (2008): 183–88. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475416.

- Grimes DA, Hulka JF, McCutchen ME. Midtrimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation versus intra-amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2 alpha: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;137(7):785-790. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(80)90886-8.

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Cates W Jr, Tyler CW Jr. Mid-trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation: A safe and practical alternative. N Engl J Med. 1977;296(20):1141-1145. doi:10.1056/NEJM197705192962004.

- Grimes DA, Smith MS, Witham AD. Mifepristone and misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation for midtrimester abortion: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2004;111(2):148-153. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00044.x-i1.

- Grossman D, Blanchard K, and Blumenthal P. “Complications after Second Trimester Surgical and Medical Abortion.” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 31 (2008): 173–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475415.

- Herabutya Y, Chanarachakul B, Punyavachira P. Induction of labor with vaginal misoprostol for second trimester termination of pregnancy in the scarred uterus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(3):293-297. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00312-6.

- Hern WM. Fetal diagnostic indications for second and third trimester outpatient pregnancy termination. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(5):438-444. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.4324.

- Hutcheon JA, Bodnar LM, Simhan HN. Medicaid pregnancy termination funding and racial disparities in congenital anomaly-related infant deaths. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):163-169. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000583.

- Infante-Rivard C, Gauthier R. Induced abortion as a risk factor for subsequent fetal loss. Epidemiology. 1996;7(5):540-542.

- Ingham R, Lee E, Clements SJ, Stone N. Reasons for second trimester abortions in England and Wales. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31 Suppl):18-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31375-5.

- Jacot, Francis R.M. et al. A five-year experience with second-trimester induced abortions: No increase in complication rate as compared to the first trimester. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1993;168(2):633-637. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(93)90509-H.

- Jones RK and Jerman J. (2014), Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2011. Perspect Sex Repro H, 46: 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1363/46e0414.

- Lawson HW, Frye A, Atrash HK et al. Abortion mortality, United States, 1972 through 1987. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994; 171(5):1365-1372. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(94)90162-7.

- Lederle L, Steinauer JE, Montgomery A, Aksel S, Drey EA, Kerns JL. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Complications After Second-Trimester Abortion by Dilation and Evacuation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(3):585-592. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001006.

- LeFevre ML, Bain RP, Ewigman BG, Frigoletto FD, Crane JP, McNellis D. A randomized trial of prenatal ultrasonographic screening: impact on maternal management and outcome. RADIUS (Routine Antenatal Diagnostic Imaging with Ultrasound) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(3):483-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(93)90605-i.

- Lerma K, Blumenthal PD. Current and potential methods for second trimester abortion. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;63:24-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.05.006.

- Lohr, Patricia A. “Surgical Abortion in the Second Trimester.” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 31 (2008): 151–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475413.

- Mark, Katrina S. et al. Risk of complication during surgical abortion in obese women American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2018;218(2), 238.e1-238.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.10.018

- Masse NM, Kuchta K, Plunkett BA, Ouyang DW. Complications associated with second trimester inductions of labor requiring greater than five doses of misoprostol. Contraception. 2020;101(1):53-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2019.09.004.

- Mazouni C, Provensal M, Porcu G, et al. Termination of pregnancy in patients with previous cesarean section. Contraception. 2006;73(3):244-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2005.09.007.

- McNamee KM, Dawood F, Farquharson RG. Mid-trimester pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2014;41(1):87-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2013.10.007.

- Mentula MJ, Niinimäki M, Suhonen S, Hemminki E, Gissler M, Heikinheimo O. Young age and termination of pregnancy during the second trimester are risk factors for repeat second-trimester abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):107.e1-107.e1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.03.004.

- Mentula M, Heikinheimo O. Risk factors of surgical evacuation following second-trimester medical termination of pregnancy. Contraception. 2012;86(2):141-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.11.070.

- Mentula MJ, Niinimäki M, Suhonen S, Hemminki E, Gissler M, Heikinheimo O. Immediate adverse events after second trimester medical termination of pregnancy: results of a nationwide registry study. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(4):927-932. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der016.

- Monier, Isabelle et al. Indications leading to termination of pregnancy between 22+0 and 31+6 weeks of gestational age in France: A population-based cohort study. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2018;233: 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.11.021.

- Morotti M, Podestà S, Musizzano Y, et al. Defective placental adhesion in voluntary termination of second-trimester pregnancy and risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(4):339-342. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2011.576722.

- Morris A, Meaney S et al. The postnatal morbidity associated with second-trimester miscarriage. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2016; 29(17): 2786-2790. https://doi.org/10.3109/14767058.2015.1103728.

- Murphy LA, Thornburg LL, Glantz JC, Wasserman EC, Stanwood NL, Betstadt SJ. Complications of surgical termination of second-trimester pregnancy in obese versus nonobese women. Contraception. 2012;86(4):402-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2012.02.006.

- Newmann S, Dalve-Endres A, Drey EA. Cervical preparation for surgical abortion from 20 to 24 weeks’ gestation: SFP Guideline #20073. Contraception. 2008;77(4):308-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.01.004.

- Nucatola D, Roth N, Saulsberry V, Gatter M. Serious adverse events associated with the use of misoprostol alone for cervical preparation prior to early second trimester surgical abortion (12-16 weeks). Contraception. 2008;78(3):245-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.04.121.

- Patel A, Talmont E, Morfesis J, et al. Adequacy and safety of buccal misoprostol for cervical preparation prior to termination of second-trimester pregnancy. Contraception. 2006;73(4):420-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.004.

- Pavlicek, J., Tauber, Z., Klaskova, E., Cizkova, K., Prochazka, M., Delongova, P., … Gruszka, T. (2020). Congenital fetal heart defect – an agreement between fetal echocardiography and autopsy findings. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub., 164(1), 92-99. https://doi.org/10.5507/bp.2019.042.

- Peterson WF, Berry FN, Grace MR, Gulbranson CL. Second-trimester abortion by dilatation and evacuation: an analysis of 11,747 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;62(2):185-190.

- Pridmore BR, Chambers DG. Uterine Perforation During Surgical Abortion: A Review of Diagnosis, Management and Prevention. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2008;39(3):349-353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.1999.tb03413.x.

- Rosenfield A. The difficult issue of second-trimester abortion. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(5):324-325. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199408043310511.

- Schechtman KB, Gray DL, Baty JD, Rothman SM. Decision-making for termination of pregnancies with fetal anomalies: analysis of 53,000 pregnancies [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol 2002 Apr;99(4):678]. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):216-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01673-8.

- Kerns J, Steinauer J Management of postabortion hemorrhage. Contraception. 2013; 87(3):331-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.024.

- Shaffer BL, Caughey AB, Norton ME. Variation in the decision to terminate pregnancy in the setting of fetal aneuploidy. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26(8):667-671. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1462.

- Shannon C, Brothers LP, Philip NM, Winikoff B. Infection after medical abortion: A review of the literature. Contraception. 2004;70(3):183-190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.009.

- Shaw D, Norman WV. When there are no abortion laws: A case study of Canada. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2020; 62, 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.05.010.

- Shulman LP, Ling FW, et al. Dilation and Evacuation for Second-Trimester Genetic Pregnancy Termination, Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1990;75(6):1037-1040.

- Sonalkar S, Ogden SN, Tran LK, Chen AY. Comparison of complications associated with induction by misoprostol versus dilation and evacuation for second-trimester abortion. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;138(3):272-275. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12229.

- Struksnaes C, Blaas HG, Eik-Nes SH, Vogt C. Correlation between prenatal ultrasound and postmortem findings in 1029 fetuses following termination of pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48(2):232-238. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15773.

- Thomas EG, Toufaily MH, Westgate MN, Hunt AT, Lin AE, Holmes LB. Impact of elective termination on the occurrence of severe birth defects identified in a hospital-based active malformations surveillance program (1999 to 2002). Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2016;106(8):659-666. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.23510.

- Turok DK, Gurtcheff SE, Esplin MS, et al. Second trimester termination of pregnancy: A review by site and procedure type. Contraception. 2008;77(3):155-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.11.004.

- Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):175-183. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000000603.

- Vargas J, Diedrich J. Second-trimester induction of labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52(2):188-197. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19407525/.

- Ville Y., Cabaret A. (2005). Late Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Anomaly. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review, 16(4), 265-279. doi:10.1017/S0965539505001592.

- Von Allmen, Stephen D., Willard Cates, Kenneth F. Schulz, David A. Grimes, and Carl W. Tyler. “2. Costs of Treating Abortion-Related Complications.” Family Planning Perspectives 9, no. 6 (1977): 273–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/2134348.

- York S, Lichtenberg ES. Characteristics of presumptive idiopathic disseminated intravascular coagulation during second-trimester induced abortion. Contraception. 2012;85(5):489-495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2011.09.017.

- Zane, S., Creanga, A. A., Berg, C. J., Pazol, K., Suchdev, D. B., Jamieson, D. J., & Callaghan, W. M. (2015). Abortion-Related Mortality in the United States: 1998-2010. Obstetrics and gynecology, 126(2), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000945.