Blade Runner (1982)

“Early in the 21st century, the Tyrell Corporation advanced Robot evolution into the Nexus phase — a being virtually identical to a human — known as a Replicant.” These are the first words we see slow-crawl up the screen in the prophetic way that only late 70s and early 80s movies seem to have been able to master.

As with later movies like Jurassic Park and The 6th Day, it is the attempts of the scientists to play God that are the most frightening, more frightening even than the dire repercussions their creations will eventually bring to pass. The same can be said of Ridley Scott’s 1982 neo-noir sci-fi thriller Blade Runner, a film which has been recut and re-edited on several occasions for multiple storylines.

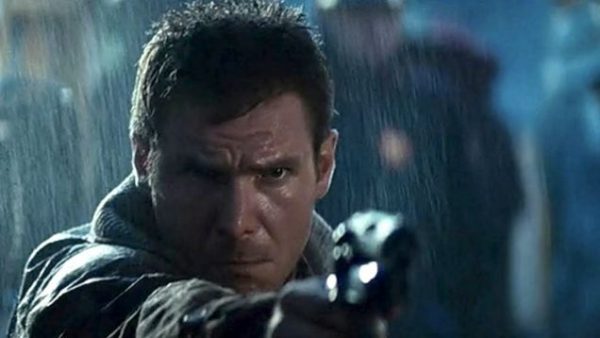

Set in Los Angeles in the once-distant year 2019, the movie follows burned-out cop Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former “blade runner,” as he tracks down rogue “replicants.” These replicants were manufactured as off-world soldiers and slave labor by the Tyrell Corporation. They were made to be “superior in strength and ability, and at least equal in intelligence, to the genetic engineers who created them.” They are humanoid — synthetic man created from biological materials, possessing human features and self-perpetuating thought — but with a four-year lifespan pre-programmed into them as a precaution. Now they are heading back to Earth — the reason is unknown, and the man set on the case is the legendary blade runner Deckard.

Deckard is reenlisted as a blade runner by his former boss Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh). The goal, he is told, is to track down and “retire” (kill) the four rogue replicants: Roy Batty, Leon, Zhora, and Pris. This means that Deckard first needs to learn more about the Nexus 6 replicants, and when he interviews their creator Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel) he discovers a deeper Machiavellian scheme. Tyrell has planted false memories into a replicant named Rachel (and possibly others), who Deckard slowly begins to fall in love with. Rachel looks human, acts human, and even believes she is a human with human memories and photographs to prove it.

This sends Deckard on a chase for any clue to help him find the rogue replicants who are at the same time slowly finagling their way closer to Tyrell. Taking advantage of gifted but dying genetic engineer J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), Roy gets a face-to-face meeting with his creator. [SPOILER] Roy confronts Tyrell, calling him “father”, demanding more life, and ultimately making him suffer the consequences for what he has done.

There you have it. [SPOILER] The creations that were intended to be life-savers have evolved into life-takers. They bleed like a human, they scream like a human, and they seem to even die like a human whenever a bullet passes through their circuitry. Yet something in Deckard cannot believe there is only machinery underneath — what that says about him has been up for debate for more than three decades. Finally coming face to face with Roy, he and Deckard must have a final showdown to see who will survive.

https://youtu.be/XTCV5BJiOhY

Riddled throughout with Biblical and mythological imagery, the film’s overlaying of themes hovers around the dangers of overreaching, of playing God and trying to manipulate (or in this case replicate) life, and the questioning of humanity. Characters are often seen quoting William Blake, self-administering a stigmata, grasping a pure white dove, or sporting serpents and serpentine tattoos. But the deeper you get dragged into this particular rainy, foggy, neo-noir world, the more you begin to admire Blade Runner as a moviegoing experience.

Scott’s cathedral-esque scenes alone are worth admission. Ford’s performance as Deckard, teeter-tottering between toughened and grizzled cop and then fragile human just moments later, is still among his best ever. And after a while the chiaroscuro-like lighting effects begin calling to mind moral questions before they are even posed in the movie. Characters’ faces are split in half light, they pass through shafts of light sent from above, and the light and dark portrayals almost become spotlights for the audience’s moral inner voice.

Blade Runner is a bleak future worth revisiting, if not simply to warn us in the manner of bygone prophets then perhaps to show us that life in the hands of amoral science presents dark and dreary possibilities.

Blade Runner’s MPAA rating is R for violence, some sexuality, and brief language and nudity. Ridley Scott directs. Loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Running time: 117 min.

— Justin Petrisek is a writer based out of Virginia. He received his M.F.A. in creative writing and M.A. in literature from George Mason University as well as an M.A. in theology from the Augustine Institute.