Oklahoma Considers Law Protecting Disabled Babies from Abortion

March 21 was World Down Syndrome Day. Fitting, then, that on the same day Oklahoma’s House of Representatives passed its Prenatal Nondiscrimination Act of 2017.

HB 1549 passed the House by a vote of 67 to 16, and now moves on to the state senate. The bill prohibits abortions sought solely because the unborn child has been diagnosed with “either Down syndrome or a potential for Down syndrome” or “with either a viable genetic abnormality or a potential for a viable genetic abnormality.” If either or both of these provisions “is held invalid as applied to the period of pregnancy prior to being viable, then it shall remain applicable to the period of pregnancy subsequent to being viable.”

Violation of the law would make the guilty physician liable for damages and subject to a suspension or revocation of his or her medical license. There would be no risk of punishment for women seeking abortions: “Any woman upon whom an abortion in violation of the Prenatal Nondiscrimination Act of 2017 is performed or attempted may not be prosecuted under this act for a conspiracy to violate this act or otherwise held criminally or civilly liable for any violation.”

The bill’s chances of making it through a senate chamber populated by 41 Republicans and just six Democrats onto the desk of Republican Governor Mary Fallin are high.

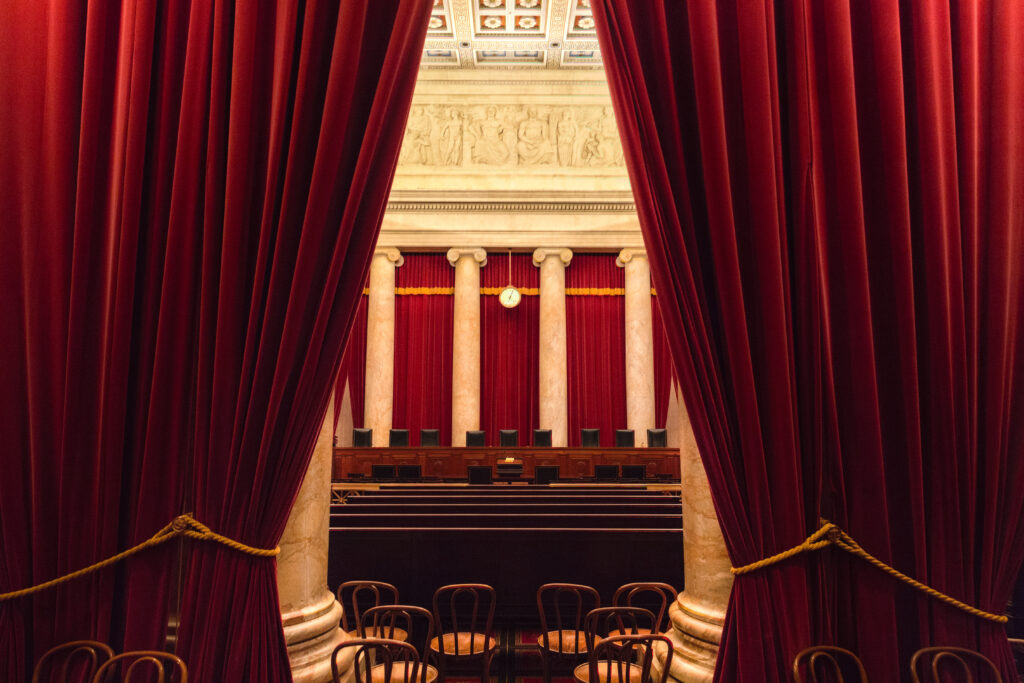

Only two states have thus far enacted disability discrimination abortion bans: North Dakota in 2013, and Indiana in 2016. Indiana’s law has been blocked from going into effect by a court order. North Dakota’s law, while in effect, has not led to any prosecutions as of summer 2015. North Dakota houses only one abortion facility—Red River Women’s Clinic in Fargo—and that facility dropped its legal challenge to the disability discrimination portion of the state’s 2013 abortion legislation because it reportedly does not perform abortion for reasons of genetic disability and so claims to be unaffected by the law.

The example of Red River Women’s Clinic points to the need for abortion facilities to be required to ascertain the reason(s) their clients seek abortion. There is good reason for abortionists to be required to do so—many women seeking abortion are affected at least in part by factors such as coercion and outside pressure. Somewhere between 30 to over 60 percent of women seeking abortion in the United States do so under pressure from the child’s father, parents, family, friends, and even employers. Women seeking abortion partly as a response to these pressures deserve to be made aware of potential alternatives, such as adoption, pregnancy help centers, and the existence in every state of safe haven laws allowing mothers to give up their newborn children as wards of the state without facing penalties.

What can be said about coerced abortions can also be said about abortions sought on the basis of the child’s sex or disability. Providers should be required to ascertain whether women are seeking abortion because of a diagnosis of disability and be required to inform the woman of alternatives. Laws such as this one take the further step of outlawing discriminatory abortions outright.

While most abortions after 20 weeks are not chosen for reasons of fetal anomaly, genetic discrimination abortions are a major concern both in the United States and abroad. Currently most disability discrimination abortion occurs after 20 weeks due to the technological state of diagnostic tests for disability, but newer non-invasive prenatal screening technologies will provide for earlier, more accurate, and less risky diagnoses of fetal disability, as disability rights advocate Mark Bradford explains in this interview. This technology will lead to more unborn babies diagnosed with Down syndrome being aborted, especially if women are not given accurate information about the condition in the modern world (such as its greatly increased life expectancy) and about supportive communities.

Bradford points to the latest research by Dr. Brian Skotko and his colleagues, estimating that live birth prevalence for Down syndrome in the United States is about 5,300 births each year. Taking account of losses of babies with Down syndrome due to natural causes such as miscarriage, Skotko estimates that abortion of babies with Down syndrome has reduced the population of people with Down syndrome in the United States by 30 percent since 1974. In recent years, somewhere between 70 and 90 percent of parents receiving a Down syndrome diagnosis for their unborn child have chosen abortion.

In some areas of Europe, the abortion rate following a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome surpasses 90 percent. According to the BBC, the termination rate for unborn babies diagnosed with Down Syndrome in Iceland is 100 percent.

Should Oklahoma become the third state to prohibit abortion on the basis of genetic disability, its law will likely face a legal challenge. Regardless, laws such as this one serve to protect the most vulnerable and force the issue of the humanity of the unborn child, who is entitled to equal protection of the law against discrimination on the basis of race, sex, disability, or condition of dependency, as are we all.

Tim Bradley is a research associate at the Charlotte Lozier Institute.