Supporting Mothers, Strengthening Futures: Reforming Arkansas’s Policies for Families with Young Children

By Naomi Lopez, M.A.

This is Issue 108 of the On Point Series.

Note: This paper was developed in conjunction with a similar state-focused paper by the same author, resulting in some portions of introductory and general text that appear in both papers.

Executive Summary

- The first 1,000 days of a child’s life – from conception to age two – are critical to brain development, emotional health, and physical well-being. This makes support for pregnant women and mothers of young children in need during this timeframe especially important.

- Arkansas has dozens of programs addressing health and well-being, financial assistance, care coordination, material support and more that assist mothers of young children. Yet, most have their own application processes and varying eligibility requirements, which can be overwhelming to navigate.

- Reforms that aim to strengthen Arkansas families in need could include: streamlining fragmented bureaucracies through AI-driven integration; reducing child care costs and increasing access by rethinking regulations; smoothing the benefits cliff with transitional benefits that aim to bridge the move from public assistance to self-sufficiency, and promote the availability of doulas for maternal health support.

Introduction

The Case for Investing in Families with Young Children

Arkansas is one of many states that have been strengthening support for pregnant women and young families and continues to seek opportunities for improvement.[1] Supporting mothers and young children isn’t just the right thing to do—it’s one of the smartest investments that Arkansas can make. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are critical for brain development, emotional health, and physical well-being.[2] Research consistently shows that children who receive adequate care, nutrition, and support during this period are more likely to succeed in school, maintain good health, and grow into productive members of society.

During the October 2024 vice presidential debate, then-U.S. Senator J.D. Vance highlighted the growing political focus on family support, proposing a $5,000-per-year child tax credit.[3] Federal initiatives like this are valuable and work in tandem with states on the frontlines in administering programs that directly support mothers and children. These include healthcare, child care, food assistance, and early education — and Arkansas already allocates billions of dollars to these efforts.[4]

Despite substantial investment, many of these resources fail to achieve their intended impact. Inefficiencies, fragmentation, and a lack of accountability plague existing systems, leaving young mothers and families to navigate a maze of disconnected programs. From unaffordable child care to the benefits cliff that punishes upward mobility, Arkansas families face systemic barriers that prevent them from achieving stability and success.[5], [6]

This paper examines these challenges and outlines actionable steps that Arkansas policymakers can take to address them. Arkansas can develop a family-centered model that delivers real results by removing burdensome regulations, creating streamlined systems, and ensuring that taxpayer dollars are used effectively. The state has a unique opportunity to lead innovative reforms that prioritize families and strengthen communities.

The current labyrinth of overlapping programs and piecemeal initiatives is a relic of the past—far removed from what any state would design if starting fresh today. It’s time to move beyond Band-Aid fixes and build 21st-century solutions that address the needs of modern families while delivering accountability for taxpayers.

The Importance of the First 1,000 Days

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life — from conception to about age two — represent a period of development unlike any other. This period is marked by extraordinary growth: a child’s brain forms over a million neural connections every second, building pathways for learning, emotional regulation, and physical health.[7] Early experiences during this window, whether positive or negative, have a profound and lasting impact.

Positive influences — such as proper nutrition, stable relationships, and consistent care —strengthen neural pathways and promote healthy development. On the other hand, challenges like stress, neglect, or inadequate nutrition disrupt brain development, leading to deficits that are difficult to reverse.[8] Nutritional support is particularly vital during this period. Nutrients such as protein, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids play a crucial role in cognitive and physical growth.[9] Without these essentials, children face risks of stunted development and long-term health challenges.[10]

Equally important are secure, nurturing relationships with caregivers. These bonds provide the emotional foundation that children need to thrive and foster social skills and resilience.[11] Conversely, toxic stress—caused by prolonged instability, neglect, or abuse—activates responses that can damage brain architecture and hinder a child’s potential.[12]

Investing in this critical period isn’t just about survival—it’s about creating the conditions for children to thrive. Arkansas has an obligation to prioritize policies that address the unique needs of the first 1,000 days, creating ripple effects that benefit families and communities and determine the state’s future.

Obstacles Facing Families

Summary

If Arkansas families cannot make ends meet, then they cannot take advantage of those critical first 1,000 days. Sadly, the reality of poverty, and the ensuing struggles of families to provide proper nutrition and care, can cause generational disadvantages. Though these issues might feel intractable, the Convergence Collaborative on Supports for Working Families sought solutions through a year-long initiative. Convergence, a facilitator of nonpartisan collaboration, brought together experts from across the political and ideological spectrum — leaders in areas including business, early childhood education, research, and advocacy — to identify the key obstacles preventing families from thriving.[13] Through monthly meetings, these thought leaders pinpointed systemic barriers and proposed action.

One major obstacle identified by the Collaborative is the unaffordable cost of child care. For many families, especially those with low-to-moderate incomes, the price of quality child care is out of reach. This could force parents into difficult circumstances: working longer hours to pay for care or relying on unreliable or low-quality options. Parents—particularly mothers because of the time spent in recovery from childbirth and breastfeeding—often find themselves stuck between rigid job demands and caregiving responsibilities. The high costs of care coupled with limited options can be an insurmountable and constant struggle, limiting opportunities for career growth and financial stability.[14] Employers, think tanks, and other stakeholders in Arkansas cite child care accessibility “as the most pressing issue” for working families, according to a report from THV11.[15]

Even if a parent wants to leave the workforce entirely, not every parent can afford to do so. These trade-offs can harm long-term economic security and lead to inconsistent care that harms children’s development. [16], [17] Given the literature on a child’s first 1,000 days, developmental issues can be irreversible, no matter what improvement a family sees in its financial situation.

The fragmented and inefficient nature of public programs is another hindrance to delivering quality child care to all families. The Collaborative found that families are often forced to navigate a labyrinth of services, each with its own applications, eligibility requirements, and bureaucratic hurdles. These disconnected programs waste time, energy, and resources, making it harder for families to access the help that they need. For struggling parents, especially young mothers, this complexity feels overwhelming and discouraging.

The benefits cliff compounds these issues. Families can face a sharp reduction in benefits when they earn even slightly more income, creating a punishing disincentive to advance economically.[18] This structure traps families in a cycle of dependency, where efforts to improve their financial situation can paradoxically leave them financially unstable.

With complex programs, expensive child care, and the benefits cliff, Arkansas must act quickly to help raise a healthy, stable, and productive generation.

Overwhelming Bureaucracies and Program Duplications

Arkansas’s network of programs that help parents and children during the first 1,000 days spans dozens of state- and federally-funded initiatives (see Appendix A).[19] While these programs are well-intentioned, their fragmented nature and lack of accountability [20] hinder their effectiveness and waste precious taxpayer resources.

The complexity begins with the sheer number of programs, which address key focus areas such as health and well-being, care coordination, financial assistance, and material support. For instance, for health and well-being alone, there are more than 20 programs such as ARKids First, the Nurse-Family Partnership, and Parents As Teachers. There are also multiple nutrition assistance programs with separate applications and management. Most programs and initiatives operate independently, resulting in overlapping purposes and disconnected agency administrations.

Of the dozens of programs, more than half have varied eligibility requirements, most with their own application processes and agency contacts. This is a system that can overwhelm a single mother with a small child. Instead of focusing on their children’s health and development, mothers are forced to contend with information-gathering and navigating the bureaucratic maze. In some instances, they act as their own case managers in a system designed more for enshrining bureaucracy than achieving family success.

Worse, taxpayers lack data on the programs that they fund. What are the impacts on family well-being as the result of each program? How much of every dollar reaches the intended recipient? Which are the most- and least-effective programs in meeting their stated goals? Aside from a few programs, the state doesn’t require programs to report the extent to which resources reach those in need. Without meaningful data, it’s impossible to ensure that these efforts fulfill their mission.

If Arkansas’s state programs are anything like those at the federal level, then benefits must pass through a vast workforce of middlemen before they land in the pockets and pantries of families in need.[21] With 56,621 full-time state employees, Arkansas could find more direct ways of delivering life-saving resources to families.[22]

As it stands, accessing Arkansas programs is like navigating a labyrinth of multiple overlapping levels. A better system would be family-centered, streamlined, and outcome-driven. Families would have a single point of access, and resources would be allocated based on clear evidence of recipient need and impact.

Reforming this broken system is both a moral and practical imperative. By consolidating overlapping initiatives, introducing robust accountability measures, and focusing on outcomes, Arkansas can create a support network that truly serves families. The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are too important to leave the current system as-is. It’s time to rebuild with families—not systems—in mind.

The High Cost of Child Care

In 2021, the average annual cost of a toddler’s child care in a licensed Arkansas facility was $6,800.[23] For a single mother with earnings at the federal poverty level ($19,720), child care alone consumes more than one-third of her total income.[24] This leaves families struggling to cover other essential needs like housing, food, and transportation.

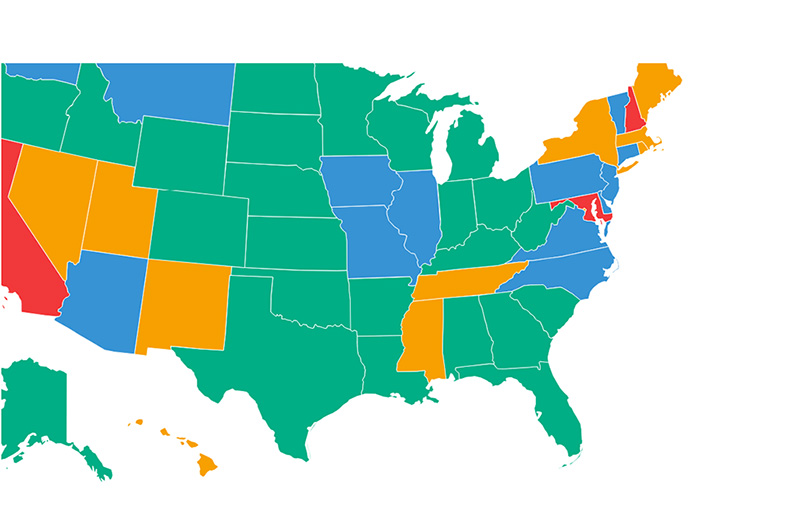

Arkansas’s regulations likely contribute to these high costs. According to the Childcare Regulation Index, 15 states are less restrictive than Arkansas because they impose fewer regulations on providers, including Louisiana, Arkansas’ neighbor to the south.[25] These regulations are costly and reduce supply, without any clear evidence of improved care quality. They create unnecessary barriers for families, especially those with low incomes.

The Childcare Regulation Index highlights the ways in which stringent requirements — such as staffing ratios, licensing fees, and facility standards — increase operational expenses for child care providers.[26] For example, Arkansas enforces a staff-to-child ratio of 1:5 for infants up to age 18 months while Idaho, New Mexico, and Georgia use a ratio of 1:6 for children of similar ages.[27], [28] Retaining staff and volunteer background checks and safety requirements would be important, while also exploring alternative requirements that might increase the availability of child care providers without impacting quality.

Families often pay for these rules and regulations in the form of higher fees.[29] What’s more, the Childcare Regulation Index notes there is a weak relationship between the quality of child care and the regulations it has documented.[30]

Additionally, restrictive regulations tend to limit the supply of child care, as the high cost of compliance deters providers from entering the market or expanding their services. As a result, families in Arkansas face fewer options, not least in the “child care deserts” where rural or low-income residents reside.[31]

Arkansas’s child care system arguably places an outsized burden on low-income households, exacerbating inequalities and making it harder for parents to work and provide for their families. Reforming these regulations to balance affordability, accessibility, and quality is essential to addressing the child care crisis in Arkansas. Reducing unnecessary restrictions and facilitating providers’ entry into the market could reduce costs and expand options for families in need.

The Benefits Cliff

Children need stability during their first 1,000 days, and families are destabilized when their responsible choices ultimately result in a dramatic drop in assets.

The “benefits cliff” happens when earning more money leaves a person or family worse off financially due to a loss of eligibility for certain benefits. This problem disincentivizes marriage, full-time employment, and other choices that would advance a low-income parent’s career.[32]

A parent accepting a promotion at several dollars more per hour can lose so many benefits that her family becomes poorer.[33] An example from Circles, an initiative to reduce poverty, illustrates how a single mother in Washington County, Arkansas, faces significant financial challenges due to the benefit cliff.[34] If the hourly wage of this hypothetical single mom exceeds $13, she loses access to Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits for her and her two young children. At more than $19.50, she loses free and reduced lunch coverage for her children’s meals at school. The most drastic impact occurs at $25 per hour when she loses her $5,991 annual child care subsidy entirely. These abrupt losses in nutrition and child care support leave her worse off financially despite earning a higher wage, highlighting the unintended consequences of the current system. In contrast, her Section 8 housing assistance decreases gradually as her income increases, reaching $0 at $16 per hour, allowing for a smoother transition.

To give parents better options, policies need to change so that benefits gradually decrease as income rises. This would keep families from falling off the benefits cliff by ensuring that hard work and career growth are always rewarded.

Maternal Health

One of the most troubling trends in maternal health has been the increase in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR), or deaths per 100,000 births, in the U.S. over a roughly 20-year period as the MMR generally decreased in other developed nations.[35] The number of maternal deaths in the U.S. ratio more than doubled from 1999 to 2019,[36] and gaps persist based on the race and age of the mother.[37] Leading and emerging causes of maternal death—cardiovascular conditions, hemorrhage, and mental health crises, including self-harm and overdose—may be prevented with timely intervention and adequate care.[38]

Arkansas has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the United States. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), between 2018 and 2022, Arkansas reported 69 deaths per 180,269 live births — a maternal mortality rate of 38.3.[39] Only three states have higher maternal mortality rates than Arkansas.

In order to begin addressing this, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders issued an Executive Order “To Support Moms, Protect Babies, and Improve Maternal Health” in March of 2024.[40] This ongoing strategic effort, referred to as “Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies,” involves a Strategic Committee for Maternal Health and more than 100 stakeholders from across the state and includes recommendations for access to maternal care.[41]

While Arkansas’s initiative to convene stakeholders and prioritize maternal health marks an important first step, expanding access to prenatal and postpartum support services specific to the needs of at-risk patients will require innovative approaches. To implement many of the recommendations made by the Strategic Committee, the Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies Act was introduced in February 2025[42] and signed into law later that month by Gov. Sanders.[43]

Reform Recommendations

Streamlining Bureaucracies and Consolidating Programs

Arkansas has an opportunity to modernize its family-support programs by leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). Implementing AI-driven analysis will identify redundancies, target the recipients of resources more precisely, and provide publicly available information on program effectiveness. Integrating APIs across systems such as child care, nutrition assistance, and healthcare will enable seamless data sharing, creating a single-entry, one-stop eligibility system that simplifies access and reduces bureaucratic confusion for families.

AI can analyze program participation, spending patterns, and service delivery gaps to highlight areas for improvement. For instance, it has the capacity to identify families eligible for programs but not yet enrolled, ensuring resources reach underserved populations. APIs facilitate real-time data exchange between agencies, enhancing efficiency and accuracy in service provision.[44] Public dashboards and reports, powered by these technologies, would enhance transparency, building trust by showing taxpayers detailed information on spending and outcomes.

Maryland is one state that recently announced an initiative to modernize its Departments of Health and Human Services, with assistance from its Department of Information Technology.[45] The initiative rebuilds state government infrastructure to support integrated services, including through an API-driven screening tool that allows Maryland residents to, in just a few steps, check their eligibility for five programs at once.[46]

By adopting similar strategies, Arkansas can build upon its current efforts to integrate data across programs and create family-support systems that are responsive, efficient, and quickly administered to the residents who truly need them.[47] Implementing AI-driven analysis and API integration lays the foundation for a unified, family-centric model that better serves all Arkansans. Other state legislatures will want to follow Arkansas’s example after seeing the fruits of its technological reforms: a system of social services that facilitates eligibility checks, benefits delivery, interagency communication, and evaluation. Importantly, the transparency will show Arkansans just how hard their tax dollars work to nurture children during their first 1,000 days.

Making Child Care More Affordable and Accessible

Because of high cost and limited supply, Arkansas faces pressing challenges in expanding access to affordable child care to families across the state.

Lawmakers and policymakers could reevaluate educational and training requirements for child care licensing and certification. While formal credentials are important, they sometimes exclude experienced caregivers who possess the necessary skills but lack specific degrees or certifications. Allowing demonstrated experience and a demonstration of skills mastery to substitute for formal education and training could expand the child care workforce. In addition, volunteers, even when their work counts toward the staffing ratios, could also be provided these additional flexibilities. These approaches, coupled with maintaining staff and volunteer safety vetting, may reduce hiring barriers, enabling more individuals with practical experience and a trustworthy record to contribute to high-quality care, while also lowering operational costs for providers.

One proposal being discussed in Tennessee involves repurposing vacant or underutilized public school properties for child care services.[48] By leveraging existing public infrastructure to lower facility costs, it becomes easier for providers to enter the market. By transforming surplus school properties into child care centers, Arkansas could similarly address service gaps in child care deserts. Proposals to place child care in a school-owned property should also initiate conversations on zoning reform.

Together, these recommendations aim to create a more accessible and affordable child care system in Arkansas. By utilizing public resources and creating pathways for experienced and volunteer caregivers, the state can better support families and ensure that high-quality child care is within reach for more Arkansans.

Addressing the Benefits Cliff

The benefits cliff hurts low-income families that are striving to achieve financial independence. Transitional benefits are a practical solution, providing a bridge as families move from public assistance to self-sufficiency. By gradually phasing out benefits instead of abruptly cutting them, transitional benefits ensure that families are better off earning higher wages, rather than face the counterintuitive penalty of losing crucial support when they start to progress financially.

A report from the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity highlights the importance of transitional benefits in Montana’s welfare system.[49] Their analysis found that transitional benefits — such as extending child care as income rises —help smooth the steep drop-off in resources that families experience when their earnings increase. Compared to traditional welfare programs, this approach incentivizes work and fosters financial independence.

In Arkansas, a similar approach is both needed and feasible. Arkansans who express a desire to work and improve their financial circumstances may be discouraged by the financial realities of the benefits cliff. This dynamic undermines economic mobility and leaves mothers dependent on assistance programs that might be the only way to meet their children’s needs during those critical first 1,000 days.

Arkansas has an opportunity to scale up transitional benefits, such as child care, to create bridges for families transitioning to financial independence. This approach not only aligns with Arkansans’ desire to work, but entire communities are strengthened when each family fosters economic stability.

A well-designed system that supports families with young children during this critical period would serve as both a safety net and a springboard, helping parents move beyond the benefits cliff and towards lasting success. Arkansas can lead the way by showing how thoughtful reforms can empower families while reducing dependency and promoting opportunity.

Promoting Healthcare Access

Arkansas is the one state that hasn’t extended Medicaid benefits to women one year postpartum or have a current legislative bill under consideration to do so.[50] Postpartum women who qualify for Medicaid in Arkansas can obtain private health insurance coverage through the state’s ARHOME program.[51]

Private health insurance coverage generally provides better access to care compared to traditional Medicaid, particularly for specialized services. Specialized care in the areas of mental health, cardiology, and maternal-fetal medicine are essential for addressing the leading and emerging causes of maternal mortality.

While advocates of extending Medicaid benefits to postpartum women argue that the administrative burden for enrolling in ARHOME is cumbersome, private coverage typically includes fewer administrative barriers, such as prior authorizations[52], [53] and limited provider availability,[54] which can delay care under traditional Medicaid, assuming that there even is a specialized provider open to new Medicaid patients.[55] Too often, having a Medicaid card does not ensure access to care.

In Arkansas, doulas are trained “birth coaches” who provide supportive care during labor and delivery, including physical, emotional, and informational support.[56] Doulas provide critical, evidence-based support throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, contributing to better maternal and infant health outcomes. Doula-assisted births are associated with lower rates of preterm births, cesarean sections, and complications during delivery.[57], [58]

Arkansas lawmakers recently adopted Medicaid reimbursement policies for prenatal and postpartum doula services through the state’s home visitation programs, as was recommended by the state’s Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies strategic committee.[59] This was an important first step in expanding access to maternal healthcare support services, particularly in underserved rural and urban areas.

Arkansas should also eventually seek to further expand doula services, allowing them to serve as “birth coaches” during labor and delivery if the patient so chooses, further helping to bridge gaps in culturally competent care by providing tailored support to women from diverse backgrounds, addressing the racial and socioeconomic disparities that may contribute to poor healthcare outcomes.

By leveraging private insurance models for postpartum women and expanding the availability of doulas under the Medicaid program, Arkansas is bridging gaps in care, ensuring more comprehensive and continuous healthcare during the critical postpartum period.

Conclusion: Building a Stronger Arkansas

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life represent a period of opportunity to shape the health, education, and well-being of future generations. Arkansas’s current systems, while well-intentioned, are hindered by inefficiencies, high costs, and outdated structures that can fail to serve families effectively. By addressing these challenges with bold, family-centric reforms, Arkansas can lead the way in creating a model that empowers mothers, strengthens communities, and builds a more prosperous future.

This report highlights four key areas for action:

- streamlining fragmented bureaucracies through AI-driven integration,

- reducing child care costs and increasing access by rethinking regulations,

- eliminating the benefits cliff with transitional benefits, and

- expanding the availability of doulas as “birth coaches” through Medicaid reimbursements to support and improve labor and delivery.

These reforms are practical, achievable, and grounded in the urgent need to support families in vulnerable times—a mother’s postpartum days and a child’s first 1,000 days. These reforms are about improving outcomes for children and building a more prosperous Arkansas for those families whose futures could be positively impacted with more effective supports in place.

It’s time to move beyond the last century’s outdated systems and take bold steps toward building the streamlined, efficient, and family-centered programs that families deserve. This is not just a policy challenge — it’s a moral and economic imperative. With thoughtful reforms and determined action, Arkansas can set a new standard for how states support their most valuable resource: their families.

Appendix A, listing programs and their program eligibility, application, and reporting requirements, may be accessed here.

Naomi Lopez is the Founder & Principal of Nexus Policy Consulting. With more than 30 years of public policy experience, she has previously served organizations including the Goldwater Institute, Illinois Policy Institute, the Pacific Research Institute, the Institute for Socioeconomic Studies, and the Cato Institute. A frequent media guest and public speaker, Naomi has authored hundreds of studies, opinion articles, and commentaries. She holds a B.A. in economics from Trinity University in Texas and an M.A. in government from Johns Hopkins University.

[1] See, for example, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ “E.O. 24-03: Executive Order to Support Moms, Protect Babies, and Improve Maternal Health,” 6 Mar. 2024. Available at: https://governor.arkansas.gov/executive_orders/e-o-24-03-executive-order-to-support-moms-protect-babies-and-improve-maternal-health/.

[2] 1,000 Days, “Resources.” Available at: https://thousanddays.org/resources/?_topics=1000-day-window.

[3] Messerly, Megan, “JD Vance: Republicans need to ‘earn’ trust back on abortion,” Politico; Oct. 2024. Available at: https://www.politico.com/live-updates/2024/10/01/vance-walz-vp-debate-tonight/vance-gop-earn-trust-abortion-00182020.

[4] State of Arkansas, “Funded Budget: Fiscal Year 2024.” Available at: https://www.dfa.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/fy2024_funded_budget_schedule.pdf.

[5] Grajeda, Antoinette, “Arkansans face more challenges than most accessing child care, report shows,” Arkansas Advocate; 14 June 2023. Available at: https://arkansasadvocate.com/2023/06/14/arkansans-face-more-challenges-than-most-accessing-child-care-report-shows/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWhile%20I%20know%20that%20there,care%20more%20affordable%20and%20accessible.

[6] Circles NWA, “The Cliff Effect: When Earning More Means Having Less.” Available at: https://www.circlesnwa.org/cliff-effect.

[7] Graff, Frank, “In Babies, Crucial Neural Connections Happen Before Age Three,” PBS North Carolina; Sept. 2021. Available at: https://www.pbsnc.org/blogs/science/in-babies-crucial-neural-connections-happen-before-age-three/.

[8] Lake, Anthony, “The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are most important to their development – and our economic success,” World Economic Forum; Jan. 2017. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2017/01/the-first-1-000-days-of-a-childs-life-are-the-most-important-to-their-development-and-our-economic-success/.

[9] Likhar, A and Patil, MS, “Importance of Maternal Nutrition in the First 1,000 Days of Life and Its Effects on Child Development: A Narrative Review,” Cureus, Volume 14, Issue 10, Oct. 2022. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9640361/.

[10] Cusick, SE and Georgieff, MK, “The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the ‘First 1000 Days,’” The Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 175, Aug. 2016. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4981537/.

[11] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Relationships: The Foundation of Learning and Development,” Infant/Toddler Resource Guide. Available at: https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/infant-toddler-resource-guide/infanttoddler-care-providers/relationship-based-care.

[12] Center on the Developing Child, “Toxic Stress,” Harvard University. Available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/key-concept/toxic-stress/.

[13] Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, “Convergence Collaborative on Supports for Working Families: Blueprint for Action,” Jan. 2024. Available at: https://convergencepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Convergence-Collaborative-on-Supports-for-Working-Families-Blueprint-for-Action.pdf.

[14] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” Sept. 2021. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-Economics-of-Childcare-Supply-09-14-final.pdf.

[15] Johnson, Mackailyn, “Arkansas’s childcare crisis: High costs, workforce issues, among biggest factors impacting parents,” THV11; 26 Nov. 2024. Available at: https://www.thv11.com/article/news/health/navigating-arkansas-childcare-crisis/91-e602a854-8a3b-4428-84a6-e58357eeb1db.

[16] DePillis, Lydia, Smialek, Jeanna and Casselman, Ben, “Jobs Aplenty, but a Shortage of Care Keeps Many Women From Benefiting,” New York Times; July 2022. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/07/business/economy/women-labor-caregiving.html.

[17] Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, “Convergence Collaborative on Supports for Working Families: Blueprint for Action,” Jan. 2024. Available at: https://convergencepolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Convergence-Collaborative-on-Supports-for-Working-Families-Blueprint-for-Action.pdf.

[18] Circles NWA, “The Cliff Effect: When Earning More Means Having Less.” Available at https://www.circlesnwa.org/cliff-effect.

[19] Appendix A was compiled by a team of researchers at the Charlotte Lozier Institute, and an analysis of program eligibility, application requirements, and reporting requirements was conducted by a team of researchers at Nexus Policy Consulting. See https://lozierinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Arkansas_Appendix-A-1.pdf.

[20] In the author’s analysis of programs, the state, often with the contribution of federal funds, operates dozens of overlapping and duplicative programs. Arkansas’s Act 414, Section 24 of 1961 requires the Department of Human Services to provide an annual report of the state’s social programs, which can provide insights into recipients and program costs. The most recent report on Fiscal Year 2023 highlights the complex bureaucracy of programs with little information on program interaction, the level of eligibles not enrolled or participating, and program participation duration, for example.

[21] For a critique of oversized programs that underdeliver in their assistance to families, see, for example, Michael Tanner, “DOGE Should Tackle Our Welfare System,” The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity Blog; 23 Dec. 2024. Available at: https://freopp.org/oppblog/doge-should-tackle-our-welfare-system/.

[22] Wickline, Michael R. “Arkansas state government reports 12 fewer full-time employees in fiscal ’24,” Arkansas Democrat Gazette; 2 Nov. 2024. Available at: https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2024/nov/02/arkansas-state-government-reports-12-fewer-full/.

[23] Grajeda, Antoinette, “Arkansans face more challenges than most accessing child care, report shows,” Arkansas Advocate; 13 June 2023. Available at: https://arkansasadvocate.com/2023/06/14/arkansans-face-more-challenges-than-most-accessing-child-care-report-shows/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CWhile%20I%20know%20that%20there,care%20more%20affordable%20and%20accessible.

[24] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “2023 Poverty Guidelines: 48 Contiguous States (all states except Alaska and Hawaii),” 2023. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1c92a9207f3ed5915ca020d58fe77696/detailed-guidelines-2023.pdf.

[25] Flowers, A.C., Geloso, V., Piano, C., et al., “Childcare Regulation Index in the States: 1st Edition,” Knee Regulatory Research Center; Oct. 2024. Available at: https://csorwvu.com/childcare_regulation_index_1/#.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Arkansas Department of Human Services, Division of Child Care and Early Childhood Education, Child Care Licensing Unit, “Minimum Licensing Requirements for Child Care Centers,” 1 Dec. 2020. Available at: https://humanservices.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020-Child-Care-centers.pdf.

[28] Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, “DRAFT report on Improving Policies and Addressing Regulatory Barriers to Grow and Support Tennessee’s Child Care Industry,” Dec. 2024. Available at: https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tacir/commission-meetings/2024december/2024Dec_Tab5ChildCare_DRAFT.pdf.

[29] For an Arkansas study on child care market prices, see, for example, McKelvey, L., Fox, L., Eubanks, R., et al. “2023 Arkansas Child Care Market Price Study,” University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (Prepared for the Arkansas Department of Education), January 2024. Available at https://dese.ade.arkansas.gov/Files/Arkansas_Market_Price_Study_2023_Final_OEC.pdf

[30] Flowers, A.C., Geloso, V., Piano, C., et al., “Childcare Regulation Index in the States.”

[31] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States,” Sept. 2021. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-Economics-of-Childcare-Supply-09-14-final.pdf.

[32] Tanner, Michael, “Fixing the Broken Incentives in Montana’s Welfare System,” Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity; Nov. 2024. Available at: https://freopp.org/whitepapers/fixing-the-broken-incentives-in-montanas-welfare-system/.

[33] National Conference of State Legislatures, “Introduction to Benefits Cliffs and Public Assistance Programs,” Nov. 2023. Available at: https://www.ncsl.org/human-services/introduction-to-benefits-cliffs-and-public-assistance-programs.

[34] Circles NWA, “The Cliff Effect: When Earning More Means Having Less.” Available at: https://www.circlesnwa.org/cliff-effect.

[35] World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division, “Trends in Maternal Mortality: 2000 to 2017,” 2019. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/featured-publication/trends-maternal-mortality-2000-2017.

[36] Fleszar, L. G., Bryant, A. S., Johnson, C. O., et al., “Trends in State-Level Maternal Mortality by Racial and Ethnic Group in the United States,” JAMA, Volume 330, Issue 1, 2023 pp.52–61. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2806661.

[37] Hoyert, Donna L, “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020,” National Center for Health Statistics; Feb. 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/E-stat-Maternal-Mortality-Rates-2022.pdf.

[38] Collier, Ai-ris Y. and Molina, Rose L., “Maternal Mortality in the United States: Updates on Trends, Causes, and Solutions,” NeoReviews, Volume 20, Issue 10, 2019, pp. 561–574. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1542/neo.20-10-e561.

[39] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Maternal deaths and mortality rates: Each state, the District of Columbia, United States, 2018-2022.” Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/maternal-mortality/mmr-2018-2022-state-data.pdf.

[40] Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ “E.O. 24-03: Executive Order to Support Moms, Protect Babies, and Improve Maternal Health,” 6 Mar. 2024. Available at: https://governor.arkansas.gov/executive_orders/e-o-24-03-executive-order-to-support-moms-protect-babies-and-improve-maternal-health/.

[41] Arkansas Strategic Committee for Maternal Health, “Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies – Maternal Health Working Group: Statewide Strategic Maternal Health Plan,” 5 Sept. 2024. Available at: https://humanservices.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/Maternal-Health-Recommendations-Final-09.05.2024.pdf.

[42] “HB 1427 – To Create the Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies Act; and to Amend Arkansas Law to Improve Maternal Health in This State.” Available at: https://arkleg.state.ar.us/Bills/Detail?id=HB1427.

[43] “Bills Signed: SB142, SB59, HB1427, HB1048, HB1223, HB1207, HB1208, HB1209, HB1210, HB1211, HB1390, HB1391.” 20 February 2025. Available at: https://governor.arkansas.gov/news_post/bills-signed-sb142-sb59-hb1427-hb1048-hb1223-hb1207-hb1208-hb1209-hb1210-hb1211-hb1390-hb1391/; See also Ryan Turbeville and Alex Kienlen, “Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signs ‘Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies Act’ into law,” n.d. Available at: https://www.fox16.com/news/state-news/gov-sarah-huckabee-sanders-signs-healthy-moms-healthy-babies-act-into-law/amp/.

[44] For an overview of APIs, see https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/api.

[45] The Office of Governor Wes Moore, “Governor Moore Announces New Mobile-Friendly Tool to Streamline Benefits Access for Marylanders,” Dec. 2024. Available at: https://governor.maryland.gov/news/press/pages/governor-moore-announces-new-mobilefriendly-tool-to-streamline-benefits-access-for-marylanders.aspx.

[46] Wintrode, Brenda, “Maryland makes it easier to determine benefits eligibility with web portal,” The Baltimore Banner; Dec. 2024. Available at: https://www.thebaltimorebanner.com/politics-power/state-government/wes-moore-maryland-benefits-ING7NQRTGBELLGT6BVHVAHUWA4/.

[47] Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, “Governor Sanders Launches AI Working Group,” 6 June 2024. Available at: https://governor.arkansas.gov/news_post/governor-sanders-launches-ai-working-group/.

[48] Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, “DRAFT report on Improving Policies and Addressing Regulatory Barriers to Grow and Support Tennessee’s Child Care Industry,” Dec. 2024. Available at: https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tacir/commission-meetings/2024december/2024Dec_Tab5ChildCare_DRAFT.pdf.

[49] Tanner, Michael, “Fixing the Broken Incentives in Montana’s Welfare System,” FREOPP White Paper; 13 Nov.2024. Available at: https://freopp.org/whitepapers/fixing-the-broken-incentives-in-montanas-welfare-system/.

[50] KFF, “Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker,” 17 January 2025. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/; Varney, Sarah, “Arkansas’ governor says Medicaid extension for new moms isn’t needed. Advisers disagree,” NPR; 13 Sept. 2024; Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2024/09/13/nx-s1-5110236/arkansas-medicaid-postpartum-12-months-sarah-huckabee-sanders.

[51] For background on the ARHOME program, see https://humanservices.arkansas.gov/divisions-shared-services/medical-services/healthcare-programs/arhome/.

[52] “Issue Brief: Prior Authorization in Medicaid” (MACPAC, August 2024), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Prior-Authorization-in-Medicaid.pdf.

[53] Karen Pollitz et al., “Consumer Problems with Prior Authorization: Evidence from KFF Survey,” KFF, September 29, 2023, https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/issue-brief/consumer-problems-with-prior-authorization-evidence-from-kff-survey/.

[54] Stephen Zuckerman, Laura Skopec, and Marni Epstein, “Medicaid Physician Fees after the ACA Primary Care Fee Bump” (Urban Institute, March 2017), https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/88836/2001180-medicaid-physician-fees-after-the-aca-primary-care-fee-bump.pdf.

[55] MACPAC, “Physician Acceptance of New Medicaid Patients: Findings from the National Electronic Health Records Survey,” June 2021. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Physician-Acceptance-of-New-Medicaid-Patients-Findings-from-the-National-Electronic-Health-Records-Survey.pdf.

[56] David Wise, “UAMS Study Finds More Doulas Needed in Arkansas,” UAMS News, November 25, 2024, https://news.uams.edu/2024/11/25/uams-study-finds-more-doulas-needed-in-arkansas/.

[57] Kenneth J. Gruber, Susan H. Cupito, and Christina F. Dobson, “Impact of Doulas on Healthy Birth Outcomes,” The Journal of Perinatal Education 22, no. 1 (2013): 49–58, https://doi.org/10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49.

[58] “March of Dimes Position Statement: Doulas and Birth Outcomes” (March of Dimes, January 30, 2019), https://www.marchofdimes.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/Doulas-and-birth-outcomes-position-statement-final-January-30.pdf.

[59] Chen, Amy, “Doula Medicaid Project: February 2024 State Roundup,” 21 Feb. 2024. Available at: https://healthlaw.org/doula-medicaid-project-february-2024-state-roundup/; Arkansas Strategic Committee for Maternal Health, https://humanservices.arkansas.gov/wp-content/uploads/Maternal-Health-Recommendations-Final-09.05.2024.pdf.