Physician-Assisted Suicide: The Path to Active Euthanasia

This is Issue 27 of the On Point Series.

Introduction

Groups promoting the legalization of physician-assisted suicide (PAS) have worked for decades to persuade state and national medical societies to support their agenda – or to take a “neutral” stance, widely recognized by advocacy groups and news media as tantamount to support.[1] In 2016, the American Medical Association (AMA) authorized its Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA) to study this issue and recommend whether the organization should change its current policy, which states that PAS “is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks.”[2]

At its June 2018 House of Delegates meeting, the AMA held two votes on this topic.

On June 11, the delegates voted by a margin of 56% to 44% not to approve CEJA’s report discussing and reaffirming the current policy against PAS.[3] This vote sent the report back to CEJA for further study, leaving the existing policy in place.

On June 12, by a similar margin, the House of Delegates explicitly voted to retain the following legislative policy, which one of its reference committees had voted to rescind: “Our AMA strongly opposes any bill to legalize physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia, as these practices are fundamentally inconsistent with the physician’s role as healer.”

The motion to restore the policy after it was deleted in committee was not subject to amendment under AMA rules. During floor debate, delegates were reminded that the proposal to rescind would not only delete the AMA stance against physician-assisted suicide, in which a physician prescribes lethal drugs but the patient has responsibility for self-administering the drugs. It would also delete the organization’s stance against legalized euthanasia, in which physicians would be called upon to administer the lethal drugs themselves (for example, by lethal injection). They voted to keep opposing legalization of either practice, rather than taking a “neutral” stance on both.

Evidently some delegates with qualms about the AMA’s principled stand against PAS still want to ensure that the organization continues to oppose legalizing euthanasia, which requires that physicians be directly involved in killing their patients.

PAS AND EUTHANASIA: DOCUMENTING THE LINKS

The AMA’s votes in June raise the question whether the distinction between PAS and euthanasia is sustainable in medical practice and public policy. If physician-assisted suicide is accepted medically and legally, is there reason to believe that barriers can be maintained against physicians being called upon to directly kill their patients?

The following considerations strongly suggest a negative answer to this question.

- The Agenda Behind the Drive to Legalize PAS

The campaign to legalize PAS in the United States has been led chiefly by the Hemlock Society, founded by Derek Humphry, and since 2007 by its successor “Compassion & Choices.”[4]

From the beginning, Hemlock worked primarily to legalize euthanasia (direct killing by doctors). At its 1986 conference in Arlington, Virginia, the organization announced that it would pursue a ballot initiative in California through a new political arm, “Americans Against Human Suffering.” This “Humane and Dignified Death Act” was approved for signature-gathering but failed to garner enough signatures to appear on the 1988 ballot. It would have amended the state constitution to permit “aid-in-dying,” defined as “any medical procedure that will terminate the life of the qualified patient swiftly, painlessly, and humanely.” It exempted from liability a physician who “administers” aid-in-dying, as well as other licensed health professionals who do so under the direction of a physician. The Los Angeles Times accurately reported that under the proposal, a terminally ill patient “could request that a doctor administer a lethal injection.”[5]

Subsequent failed efforts on the West Coast followed the same pattern. A Hemlock-sponsored legalization measure rejected by the Oregon legislature in 1991 (S.B. 1141) defined “aid in dying” as “a medical procedure performed by a physician that will end the life of the qualified patient in a dignified, painless and humane manner” (emphasis added). Likewise, Hemlock’s first ballot initiative in Washington state (Initiative 119), rejected by the voters in November 1991, would have legalized “aid-in-dying,” defined as “aid in the form of a medical service provided in person by a physician that will end the life of a conscious and mentally competent qualified patient in a dignified, painless and humane manner…” (emphasis added).

Hemlock then shifted tactics somewhat. Its next initiative for the California ballot, a “Death with Dignity Act” rejected by the voters in November of 1992 (Proposition 161), would have legalized “aid-in-dying,” defined as “a medical procedure that will terminate the life of the qualified patient in a painless, humane and dignified manner whether administered by the physician at the patient’s choice or direction or whether the physician provides means to the patient for self-administration” (emphasis added). After six years of legislative advocacy, this was apparently the first time that a Hemlock proposal introduced physician-assisted suicide as an option alongside euthanasia. Proponents and news media sometimes referred to this proposal as permitting “doctor-assisted suicide,”[6] but the Death with Dignity National Center accurately describes it as “allowing for euthanasia by lethal injection.”[7]

Only after these failures did Hemlock make a tactical decision to support a ballot initiative in Oregon (Measure 16) allowing only PAS, in which, the organization claimed, the patient must perform the final lethal act.[8] This tactic was recommended in a prestigious medical journal in November 1992 by three pro-PAS physicians, who said this narrowing of the agenda was “less than ideal” but would respond to public concerns about the risk of coercion and abuse from allowing doctors to give lethal injections.[9] Humphry agreed publicly that it might be time to “give the idea a trial,” but noted: “Change that fails to include voluntary euthanasia will be of little comfort to those whose disease means they cannot swallow, keep liquids down, or lift a cup.”[10] In November 1994 this strategy succeeded, making Oregon the first state to legalize PAS, and its law has since been the model for new laws in several other states and the District of Columbia.

However, there is no reason to believe that Hemlock’s initial agenda has been set aside. Its successor Compassion & Choices remains interested in euthanasia once PAS is more widely accepted in law and medicine. For example, speaking in Connecticut in 2014, Compassion & Choices president Barbara Coombs Lee said her organization’s immediate goal in the state was passage of a PAS measure. Commenting on euthanasia for people with dementia and other cognitive loss, she said: “It is an issue for another day but is no less compelling.”[11]

- Practical Realities of Assisted Suicide

When the people of Oregon passed the nation’s first PAS law in November 1994, supporters in the U.S. and the Netherlands immediately said this would not be sufficient.

Hemlock founder Derek Humphry wrote in early December that the new law “could be disastrous” because it did not allow doctors to provide a “lethal injection.” He said the evidence indicates that “about 25 percent of assisted suicides fail,” so Oregon’s policy “will only work if in every instance a doctor is standing by to administer the coup de grace if necessary.”[12] Prominent Dutch euthanasia practitioner Dr. Pieter Admiraal, who had conducted a four-year study of assisted suicides in the Netherlands, confirmed that about a quarter of the patients who orally self-administer the lethal drugs linger for hours or days afterward. Saying this is “not acceptable in a civilized world,” Admiraal warned Oregon voters: “You are in trouble. You have accepted phase one. Now phase two is coming.”[13]

A later study of assisted suicide and euthanasia in the Netherlands, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2000, reached the same conclusion: “In general, problems were more frequently reported in cases of assisted suicide than in cases of euthanasia. The responsible physician decided to administer the lethal medication in 21 of 114 cases in which the original intention had been only to provide assistance with suicide. In most of these cases, the patient did not die as soon as expected or awoke from coma, and the physician felt compelled to administer a lethal injection because of the anticipated failure of the assisted suicide.”[14]

Experience under the Oregon and Washington PAS laws confirms the validity of these warnings.[15]

From 1998 to 2017, a total of 1,275 patients are reported to have died from ingesting lethal medication prescribed by a physician under Oregon’s PAS law.[16] At least 34 patients have experienced complications such as regurgitating the lethal dose, and seven regained consciousness and died later, apparently of natural causes.[17] In 638 cases (101 of them in 2017) it is not known whether these complications occurred, chiefly because the prescribing physician (the only person allowed to file reports) was not present.[18] Patients are known to have taken up to 104 hours (over 4 days) to die; time from ingestion to death is unknown for over half the patients (673 out of 1,275).[19]

In Washington, whose 2008 law is similar to Oregon’s, 1,364 PAS deaths are reported from 2009 to 2017.[20] There have been at least 19 cases of regurgitation (12 of them in the last three years)[21] and 2 cases of waking up after ingesting the drugs.[22] Patients are known to take up to 72 hours (three full days) to die.[23]

These must be seen as minimum figures. In both states, the prescribing physician solely responsible for filing reports with the state health department was seldom present at the time of death, so could not observe complications or report whether those present took more active steps to cause the patient’s death.[24]

Numerous anecdotal reports give additional weight to these findings. For example, Derek Humphry’s first book on this issue, Jean’s Way, recounted how he obtained a lethal overdose of pills to assist his first wife Jean in taking her life when she was terminally ill; but his second wife, Ann Wickett Humphry, later reported that he had suffocated Jean – and that her own later effort to assist her mother’s suicide with Derek’s help, recounted in her book Double Exit, went badly, ending only when she suffocated her mother with a plastic laundry bag.[25]

And when the group Compassion in Dying (CID), founded by Hemlock official Rev. Ralph Mero, invited a New York Times reporter to observe how responsibly and humanely its members assist in suicides, the reporter found that the patient unexpectedly survived for seven hours after taking the drugs – and Mero assured her that he “was prepared and had the wherewithal” to ensure her death, apparently by fastening a plastic bag over her head. When the reporter observed that such active intervention would break CID’s supposedly careful rules, Mero said, “I guess you can accuse us of being nonspecific about that,” adding: “I think most of the individuals on our board know in their own hearts what the ethically correct thing is to do.”[26]

Statements by PAS supporters, formal studies, experience with PAS laws in the U.S., and individual accounts all confirm that deaths by PAS can be unreliable, lingering and distressing. Supporters know this and are counting on it to ensure that direct killing by doctors (“step two”) will be authorized once PAS (“step one”) is more widely accepted.

- The Legal and Conceptual Logic of a “Right” to PAS

The links between PAS and euthanasia become still clearer when we consider how acceptance of a “right” to PAS interacts with other longstanding features of the American legal system.

Currently the legal distinction between the two is that PAS proposals create an exception to the laws in effect in almost all states against one person aiding and abetting another person’s suicide;[27] euthanasia proposals create an exception to the laws in effect in every state against homicide.

In 1996 the Second Circuit Court of Appeals argued that New York’s law forbidding PAS violated the Equal Protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Terminally ill patients dependent on life support had a right to refuse such treatment, allowing them to die; but terminally ill patients not dependent on such treatment to prolong their lives, though similarly situated in terms of the burdens of the dying process, could not exercise their right to end life due to the state’s ban on PAS. The court said these patients must have access to a more active means of causing their deaths, to vindicate their equal rights under law.[28]

Against this argument, many attorneys, physicians, and ethicists pointed out that “there is a difference in kind, not merely in degree,” between withdrawal of treatment on the one hand and actions intended to cause death on the other.[29] And the Second Circuit’s decision was overturned on this basis by a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court decision, which found: “By permitting everyone to refuse unwanted medical treatment while prohibiting anyone from assisting a suicide, New York law follows a longstanding and rational distinction.”[30]

But what if that line between treatment withdrawal and PAS is erased in law, so the latter is legally authorized as one “treatment decision” among others? In law and policy, does a bright line remain between PAS and euthanasia? The two actions generally involve the same means, an overdose of barbiturates; they involve the same intent on the physician’s part, to help cause a patient’s death; and the only remaining distinction, between prescribing the lethal dose and administering it oneself, is ambiguous at best — especially for patients who may be receiving all their medications by intravenous line or feeding tube. Legal experts have pointed out that if the Second Circuit’s “equal protection” argument prevailed, it would easily override the distinction between PAS and euthanasia:

If a person otherwise “eligible” for physician-assisted suicide and otherwise determined to end his or her life by the active intervention of another needs someone else to administer the lethal medicine, how can the person be denied this right or liberty (assuming it is a right or liberty) simply because the person cannot perform the last, death-causing act alone?[31]

This warning was confirmed shortly after the Oregon law took effect. In 1999, a patient apparently found himself too physically weak to self-administer the lethal dose and his brother-in-law actively “helped” him do so. When the state attorney general’s office was asked by a state legislator whether such action is allowed under the state’s PAS law, it replied in writing:

The Death with Dignity Act does not, on its face and in so many words, discriminate against persons who are unable to self-administer medication. Nonetheless, it would have that effect… Thus, the Act would be treated by courts as though it explicitly denied the “benefit” of a “death with dignity” to disabled people.

This fact, in turn, makes the Death with Dignity Act vulnerable to challenge under both Article I, section 20 of the Oregon constitution (under which the state must make privileges and immunities available to all classes of citizens on the same terms), and Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (which, with certain exceptions, prohibits government from denying benefits or services to disabled persons).[32]

Given this legal analysis, it is not surprising that there is no record that the person in this case or any other case has faced legal liability for more actively and directly “assisting” (that is, causing) the death of a weak or disabled patient who had requested “death with dignity” under the Oregon law. The state government has effectively warned that any attempt to punish these actions could be challenged as violating both federal law and the state constitution. As noted above, it is at best unclear whether laws like those in Oregon and Washington forbid such action now.[33]

How often such actions occur in Oregon today is unknown: The attending physician who prescribes the drugs, the only person authorized to file reports, is seldom present to assess competency, voluntariness or coercion, or to observe who else (physicians or otherwise) are present or what lethal actions they may take; and the death of the patient is recorded as death by natural causes, to prevent scrutiny.[34] But the legal principles are in place to condone or ignore direct killing by those accompanying the patient.

- Public Opinion on PAS and Euthanasia

As noted above, physicians seem more opposed to active euthanasia than to PAS, because the former would impose on them the burden of being involved in directly killing their patients. The opposite seems true among the general public. Patients are not necessarily comfortable with responsibility for the final lethal action either.

Gallup polls have indicated this for many years. In 2018, for example, Gallup asked over 1,000 U.S. adults two questions:

“When a person has a disease that cannot be cured, do you think doctors should be allowed by law to end the patient’s life by some painless means if the patient and his or her family request it?” Seventy-two percent said yes, and this figure has been 69% or higher since 2013.

“When a person has a disease that cannot be cured and is living in severe pain, do you think doctors should or should not be allowed by law to assist the patient to commit suicide if the patient requests it?” Sixty-five percent said yes, and this response has differed more widely, with only 51% in support in 2013.[35]

Some caveats are in order. For example, affirmative response to the PAS question was undoubtedly boosted by inserting the reference to “living in severe pain,” which is not a factor in any PAS law in the U.S. and is seldom the reason given by patients for requesting PAS.[36] On the other hand, the reference to suicide, an accurate description of how PAS proposals change the law, may have contributed to negative responses. Affirmative response to the euthanasia question may have been enhanced by reference to a “painless means,” the euphemism “end the patient’s life” (rather than “commit homicide” or “cause death”), and the reference to including the family in the request (which is not required in any PAS law in the U.S.). But despite slight variation in the questions over the years, Gallup and other polls have long shown higher support for euthanasia performed by doctors than for PAS.

Obviously these responses are also not reliable predictors of how legislators and voters may vote on specific proposals, once they are given more time to reflect on risks of abuse and other factors. Also, the same 2018 Gallup poll received a less positive response (54%) when it asked about the moral acceptability of “doctor-assisted suicide.”

It is logical to conclude that if American society more widely accepts PAS as a legal option, then the general public will likely be primed to accept direct killing by physicians as well.

CONCLUSION

Physicians may be tempted to believe that a positive or “neutral” stance on PAS will be a stable compromise allowing them to recognize a “right to die” for some patients without being called upon to perform the lethal act themselves. There is overwhelming evidence that this belief is naïve at best. The founding intentions of the PAS movement, the grim practical realities of suicide by oral overdose, the legal principles at stake, and the state of public opinion all argue that the move from PAS to euthanasia, once the former is more widely accepted, would be not only a “slippery slope” but a virtual free fall. Physicians and medical organizations who do not want doctors to be called upon as killers should continue their strong opposition to the legalization of physician-assisted suicide.

[1] According to a national health news outlet, for example, “in Massachusetts and other states, doctors groups are dropping their opposition — a move that advocates and opponents agree helps pave the way to legalization of physician-assisted death.” M. Bailey, “As doctors drop opposition, aid-in-dying advocates pick next battlefronts,” Kaiser Health News, Jan. 28, 2018 (emphasis added), at https://khn.org/news/as-doctors-drop-opposition-aid-in-dying-advocates-target-next-battleground-states/. Also see D. Sulmasy et al., “Physician-Assisted Suicide: Why Neutrality by Organized Medicine Is Neither Neutral Nor Appropriate,” 33.8 Journal of General Internal Medicine (August 2018) 1394-9.

[2] American Medical Association, “Physician-Assisted Suicide: Code of Medical Ethics Opinion 5.7,” at https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/physician-assisted-suicide.

[3] See Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, CEJA Report 5-A-18 (2018), at https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/default/files/media-browser/public/hod/a18-ceja5.pdf.

[4] Technically C&C is a merger between the Hemlock Society and its earlier spin-off organization, Compassion in Dying. For a detailed history see Patients Rights Council, “Assisted Suicide & Death with Dignity: Past, Present & Future – Part I” (January 2005), at http://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/rpt2005-part1/.

[5] J. Dart, “Leaders Oppose Right-to-Die Initiative,” The Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1988, at http://articles.latimes.com/1988-04-21/news/mn-2551_1_religious-leaders.

[6] For example, see news articles compiled at “Proposition 161 Physician-Assisted Death,” The Los Angeles Times, http://articles.latimes.com/keyword/proposition-161-physician-assisted-death.

[7] Death with Dignity National Center, “Death with Dignity in California – A History,” https://www.deathwithdignity.org/death-with-dignity-california-history/.

[8] Note that the 1994 Oregon law, which took effect in 1997, does not use the word “self-administer,” but says more ambiguously that a “qualified patient” can “obtain a prescription for medication to end his or her life in a humane and dignified manner” (emphasis added). The attending physician is to counsel the patient on “the importance of having another person present when the patient takes the medication.” It says that nothing in the Act “shall be construed to authorize a physician or any other person to end a patient’s life by lethal injection, mercy killing or active euthanasia” (without defining these terms), but then adds that any action in accordance with the Act “shall not, for any purpose, constitute suicide, assisted suicide, mercy killing or homicide, under the law” (emphasis added), and it creates no penalty for active involvement in causing the patient’s death. “The Oregon Death with Dignity Act,” Secs. 1.01 (11), 3.01 (g), 3.14, 4.02, at https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Pages/ors.aspx. The similar Washington law of 2008, which took effect in 2009, does describe the patient as obtaining a prescription for “medication that the qualified patient may self-administer to end his or her life in a humane and dignified manner,” but defines “self-administer” as “a qualified patient’s act of ingesting medication to end his or her life in a humane and dignified manner” (emphasis added). To “ingest” something is to swallow or absorb it, not necessarily to introduce it into one’s own body. “The Washington Death with Dignity Act,” subsecs. 70.245.010 (11) and (12), at http://apps.leg.wa.gov/rcw/default.aspx?cite=70.245&full=true.

[9] T. Quill, C. Cassel, and D. Meier, “Care of the Hopelessly Ill: Proposed Clinical Criteria for Physician-Assisted Suicide,” 327.19 New England Journal of Medicine (Nov. 5, 1992), 1380-1384 at 1381. This was only a temporary or tactical proposal even for the article’s lead author. In 1994 Dr. Quill again wrote favorably about legalizing both practices: “Physician-assisted suicide is less emotionally wrenching for physicians, whereas with voluntary active euthanasia there is less chance of error in the procedure.” T. Quill, “The Care of Last Resort,” The New York Times, July 23, 1994, at 19. A second author, Dr. Diane Meier, later changed her mind on the entire issue, writing that “after caring for many patients myself, I now think that the risks of assisted suicide outweigh the benefits.” D. Meier, “A Change of Heart,” The New York Times, April 24, 1998; cited in Patients Rights Council, “Update 013: Volume 12, Number 2 (April-June 1998)”, at http://www.patientsrightscouncil.org/site/update013/.

[10] D. Humphry, “Death with Dignity Effort May Be Tried Here Again,” The San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 13, 1992, A25.

[11] L. Foster, “Compassion & Choices Draws Full House at Real Art Ways for Panel Discussion, Film,” CT News Junkie, Oct. 10, 2014, at https://www.ctnewsjunkie.com/archives/entry/compassion_choices_draws_full_house_for_panel_discussion_film/.

[12] D. Humphry, Letter to the Editor, “Oregon’s Assisted Suicide Law Gives No Sure Comfort to Dying,” The New York Times, Dec. 3, 1994, 14.

[13] Quoted in M. O’Keefe, “Dutch researcher warns of lingering deaths,” The Sunday Oregonian, Dec. 4, 1994, A1.

[14] J. Groenewoud et al., “Clinical Problems with the Performance of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the Netherlands,” 342.8 The New England Journal of Medicine 551-6 at 554; https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJM200002243420805.

[15] For overviews of how the Oregon law has operated in practice see: R. Doerflinger, “Oregon’s Assisted Suicides: The Up-To-Date Reality in 2017,” Charlotte Lozier Institute (March 2018), https://lozierinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Oregon-Assisted-Suicide-The-Up-To-Date-Reality-2017.pdf; Id., “A Reality Check on Assisted Suicide in Oregon,” Charlotte Lozier Institute (April 2017), https://lozierinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/A-Reality-Check-on-Assisted-Suicide-in-Oregon-1.pdf.

[16] Oregon Health Authority, “Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2017 Data Summary,” at 5; https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/year20.pdf.

[17] Id. at 10, 11.

[18] Id. at 10 (complications unknown in 638 cases; prescribing physician present at time of death in only 172 out of the 1205 cases reported since 2001).

[19] Id. at 11.

[20] Washington State Department of Health, “Washington State Death With Dignity Act Report” (March 2018), at 5, https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2017.pdf.

[21] Id. at 10 (on the twelve cases in 2016-17); for previous cases see Washington State Death With Dignity Act reports for 2014, at 9; for 2012, at 9; and for 2010, at 9; available at https://www.doh.wa.gov/YouandYourFamily/IllnessandDisease/DeathwithDignityAct/DeathwithDignityData.

[22] See Washington State Death With Dignity Act report for 2009 at 9; https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2009.pdf.

[23] See note 19 supra at 10.

[24] On Oregon see note 17 supra at 10; on Washington see note 19 supra at 10 (prescribing physician present at time of ingestion in 8% of cases in 2017, 9% in 2016, and 5% in 2015). Note that Washington state does not report whether the prescribing physician or any other health care provider is ever present at the time of death.

[25] See R. Marker, Deadly Compassion: The Death of Ann Humphry and the Truth About Euthanasia (William Morrow and Company 1993), at 72, 230.

[26] L. Belkin, “There’s No Simple Suicide,” The New York Times Magazine, Nov. 14, 1993, at https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/14/magazine/there-s-no-simple-suicide.html.

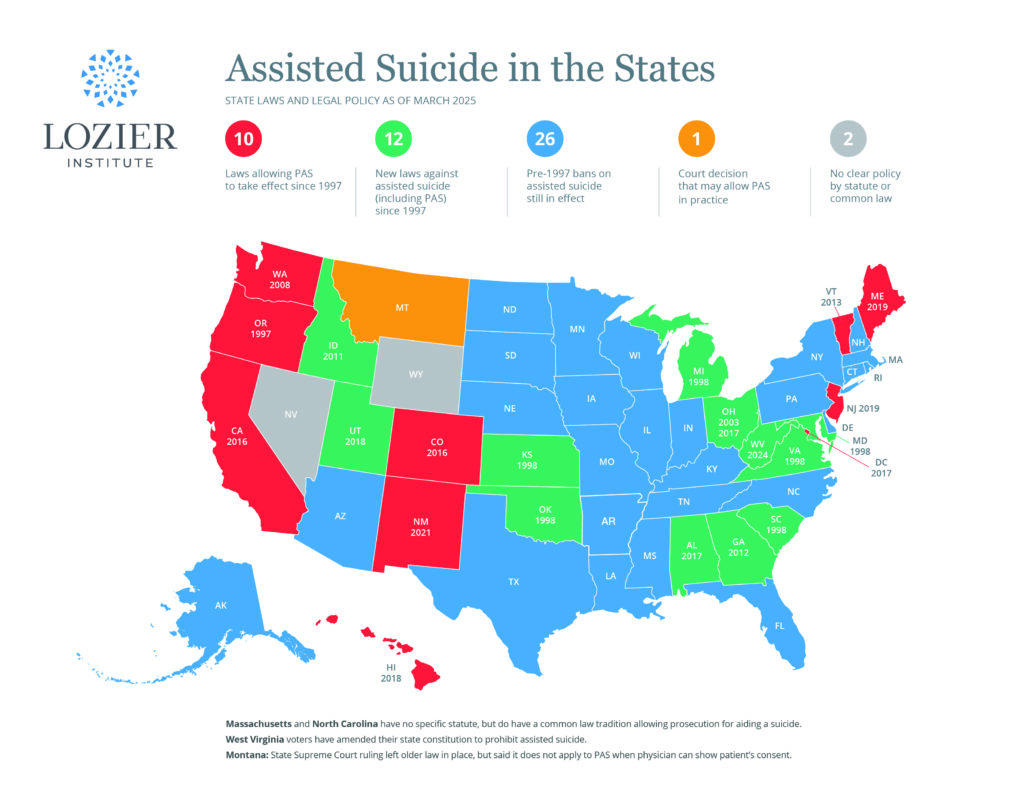

[27] See Charlotte Lozier Institute, “Assisted Suicide in the States” (2018), at https://lozierinstitute.org/map-assisted-suicide-in-the-states/.

[28] Quill v. Vacco, 80 F.3d 716 (2d Cir. 1996).

[29] See M. Somerville, Death Talk: The Case Against Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide (McGill-Queen’s University Press 2001) at 67-8.

[30] Vacco v. Quill, 521 U.S. 793, 808 (1997).

[31] Y. Kamisar, “The ‘Right to Die’: On Drawing (and Erasing) Lines,” 35.1 Duquesne Law Review (Fall 1996), 481-521 at 489 (emphasis in original).

[32] Letter of Oregon deputy attorney general David Schuman to state legislator Neil Bryant, March 15, 1999.

[33] See note 8 supra.

[34] On the prescribing physician’s absence in most cases see notes 17 and 24 supra. On falsifying cause of death in Oregon see K. Hedberg, “Oregon Department of Human Services Reporting,” in Task Force to Improve the Care of Terminally-Ill Oregonians, The Oregon Death with Dignity Act: A Guidebook for Health Care Professionals (2008), Chapter 14; http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/education/continuing-education/center-forethics/ethics-outreach/upload/Oregon-Death-with-Dignity-Act-Guidebook.pdf. Such listing of a death by natural causes is explicitly required by the Washington statute: see Washington State Department of Health, “Instructions for Physicians and Other Medical Certifiers for Death Certificates: Compliance with the Death with Dignity Act” (2009) at https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-151-DWDInstructionsForPhysicians.pdf.

[35] Gallup, “Americans’ Strong Support for Euthanasia Persists” (May 31, 2018), at https://news.gallup.com/poll/235145/americans-strong-support-euthanasia-persists.aspx. Also see Id., “U.S. Support for Euthanasia Hinges on How It’s Described” (May 29, 2013), at https://news.gallup.com/poll/162815/support-euthanasia-hinges-described.aspx.

[36] In Oregon, an average of 26% of patients (21% in 2017) have cited a concern about present or future inadequate pain control as one of the reasons for requesting lethal medication. See Oregon Health Authroity, note 16 supra, at 10. In Washington state, 38% cited this as a factor in 2017. See Washington State Department of Health, note 20 supra, at 8.