Response to Media Allegations that Abortion Restrictions Cause Maternal Mortality and Female Suicides

This is Issue 2 of the On Women’s Health Series.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision overturning Roe v. Wade, many media sources have expressed concern that implementation of abortion restrictions by individual states will worsen maternal mortality in those states, many of whom already suffer higher than average rates. This is a legitimate concern that must be addressed, because regardless of one’s personal feelings about the ethics of elective induced abortion, it is important to ensure that these restrictions do not adversely affect the health of pregnant women.

However, many of these claims are ideologically driven based on false underlying assumptions. A balanced review of the data and evidence from peer-reviewed medical literature clearly shows the opposite, that maternal health suffers with increased access to abortion.

Each concern regarding abortion restrictions and maternal health is addressed below from an evidence-based perspective, followed by a rebuttal to the most recent claims in the media.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANALYSIS OF ABORTION RESTRICTIONS AND MATERNAL HEALTH

How might abortion restrictions improve, rather than worsen maternal mortality?

- Abortion restrictions will not prohibit medical interventions for maternal life-threatening emergencies. Every state has an exemption allowing abortion when necessary to save the life of the mother if her pregnancy poses a severe risk to her life. These laws specify that a physician may use his “reasonable medical judgment” to determine if intervention is necessary in a “medical emergency”. With the exception of treatment of an ectopic pregnancy, the necessity for an abortion, defined as “action intending to end embryonic or fetal life”, to save a mother’s life is extremely rare, because usually these heartbreaking situations do not occur until the second half of pregnancy, when a woman’s obstetrician can deliver her in a safer, medically standard way, by induction or cesarean section, and often the baby’s life can be saved also. Fortunately, abortion for a maternal life-threatening condition accounts for far less than one percent of all abortions in the U.S.[1]

- Limiting abortion will prevent many vulnerable women from being exposed to the increased risk of death in the year following abortion. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) maternal mortality data has many known limitations, so an assessment of the risk of death after abortion compared to childbirth cannot be accurately measured using U.S. data. Better quality data obtained from records-linkage studies in Finland, Denmark, and the California Medicaid population all document far more deaths in the year following abortion than childbirth.[2]

- Abortion restrictions will limit later abortions which are more dangerous for a woman. Approximately 8-10% of U.S. abortions occur after the first trimester and 1% occur in the second half of pregnancy.[3] These abortions are usually performed by dilation and evacuation abortion (D&E), which is much more dangerous than earlier abortion procedures, as it requires forcibly dilating a strong muscular cervix and multiple blind passes of surgical instruments to disarticulate the fetus and remove the pregnancy tissue, with risks of hemorrhage, infection, retained tissue, damage to adjacent organs, anesthetic complications and stroke, heart attacks and deaths.[4] The CDC documents a 38% increase in mortality for each week that an abortion is performed beyond eight weeks, with 14.7-fold increased mortality early in the second trimester, 29.5-fold increase in the mid-second trimester, and a 76.6-fold increase in the risk of death to a woman from abortion after viability (approximately 22 weeks’ gestation).[5]

- Abortion restrictions will reduce the incidence of repeat abortions. Records-linkage studies document more deaths in the year following abortion than childbirth and these risks increase when women obtain multiple abortions.[6] Reducing the opportunity for repeated abortions should reduce the overall mortality rate of women of reproductive age.

- Abortion restrictions will prevent future mental health disorders in some women. Records-linkage studies document an increase in “deaths of despair” from suicide, accidents, homicide, and other high-risk taking behavior in the year following abortion compared to childbirth.[7]

- Abortion restrictions will prevent some future pregnancy complications. Surgical trauma to the uterine lining in a dilation and suction, curettage or evacuation procedure may cause an abnormal placental attachment in the next pregnancy. Placental abruption (premature separation) can occur if the attachment is not secure, and placental accreta syndrome (pathologic invasion) can occur if the attachment is too strong. These abnormal placental attachments can lead to life-threatening bleeding at delivery.[8] Also, abortion has been documented to increase the risk of a subsequent preterm birth which is associated with higher maternal mortality.[9] Limiting abortion will decrease women’s risk of maternal mortality in subsequent pregnancies for these reasons.

- Abortion restrictions may also lead to more fathers taking responsibility for their children and decrease the rates of single motherhood. Abortion has devastated the family structure and social relationships in our country, increasing the odds that a woman lives in poverty as a single mother, which is associated with medical and social conditions predisposing her to maternal mortality.[10]

- Many of the states that have implemented abortion restrictions have prioritized expanding a broad social support net to meet the needs of a pregnant mother, which is likely to improve maternal mortality. For example, Texas has allocated over $100 million over two years in Alternatives to Abortion funding. Across the U.S., approximately 2,700 pregnancy resource centers also provide (usually free) care and counseling for women in crisis pregnancies, allowing them alternatives and the material, emotional and relationship support they may need in order to welcome their children.

- Abortion restrictions are unlikely to result in instrumental “coat-hanger” septic abortions. The false but frightening narrative that a woman denied abortion will seek it in an unsafe way, resulting in 5,000-10,000 deaths yearly, drove its widespread legalization in 1973, and is being recycled today as states implement restrictions.[11] Yet, in the years prior to Roe v. Wade, the CDC documented fewer than 100 deaths yearly from both legal and illegal abortions.[12] Abortion was becoming safer long before it was legalized due to improved surgical techniques, safer anesthesia, and widespread antibiotic use. Even then, 90% of abortions were performed by physicians, albeit illegally.[13] Advances in medical care since that time continue to help women who may be injured in legal or illegal abortions.

- Abortion restrictions will encourage both men and women to change their sexual behavior and use more reliable contraception. Studies of changes in state and international laws show that with limitations on abortion, the abortion rate goes down immediately. Although the birth rate rises by a small amount temporarily, it often decreases to the prior rate with time. As the “cost” of abortion rises, women discover other ways to decrease unwanted births by preventing unintended pregnancies in the first place. In the face of restrictions, women decrease promiscuous sexual behavior and use more effective contraception.[14]

- Abortion restrictions will also reduce unwanted abortions. As many as 64% of women with a history of abortion report feeling pressured into their abortions by other people, such as their male partner or parents, or by other circumstances.[15] “Perceived pressure from others” to have an abortion is one of the risk factors for mental health problems after abortion that has been identified by the American Psychological Association, so restrictions will reduce the rate of abortion among women at high risk of negative psychological reactions to abortion, thereby reducing their rate of suicide and self-destructive behaviors.[16]

- Finally, abortion restrictions have not been shown to increase maternal mortality ratios (MMR) in other countries. In fact, the U.S. has the worst MMR of the developed countries[17] despite having very high overall abortion rates, and late-term abortion rates second only to Communist China. Countries as diverse as Chile, El Salvador, Poland and Nicaragua all saw their MMR improve after they implemented abortion restrictions.[18] Demographically similar countries – Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom – until recently had disparate abortion laws, but nonetheless a lower MMR was demonstrated in abortion-restrictive Ireland than in the abortion-permissive UK.[19]

REBUTTAL TO RECENT MEDIA CLAIMS

Commonwealth Fund:

Recently the Commonwealth Fund released an issue brief, The U.S. Maternal Health Divide: The Limited Maternal Health Services and Worst Outcomes of States Proposing New Abortion Restrictions, which caused a media sensation. The brief’s summary noted, “In states that have banned or restricted abortion access, rates of maternal and infant deaths are much higher than in states that have preserved access”, leading them to conclude, “Making abortion illegal makes pregnancy and childbirth more dangerous; it also threatens the health and lives of all women of reproductive age.”[20] Predictably, journalists immediately began parroting this bold statement, reporting that maternal death rates will continue to rise in the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs’ decision which allows legislatures to restrict abortion, worsening outcomes among vulnerable women.[21]

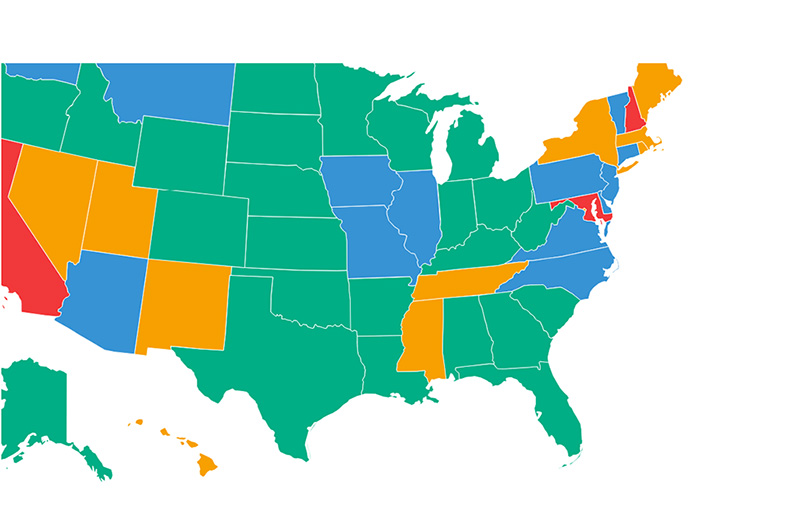

This report examined maternal mortality from the years 2018 to 2020 in 26 states that placed restrictions on abortion following the reversal of Roe v. Wade in June 2022, comparing “most restrictive,” “very restrictive,” and “less restrictive,” to 24 states and the District of Columbia that have placed few or no restrictions on abortion, characterized as “most permissive,” “moderately permissive,” and “permissive but a few restrictions.” It reported that the states with restrictions cumulatively had maternal death rates 62% higher (restrictive: 28.8 maternal deaths/100,000 live births vs. permissive: 17.8/100,000). Yet, a comparison of death rates in the non-pregnant population is instructive. Overall death rates in non-pregnant women of reproductive age (15-44 years old) were also 34% higher (restrictive: 104.5/100,000 people/year vs. permissive: 77.9/100,000). Additionally, newborn children in these states also had higher infant and perinatal mortality rates (restrictive: 6.2 deaths/1,000 births vs. permissive: 4.8/1,000).

Bias: The Commonwealth Fund describes its mission as “promot(ing) a high-performing equitable health care system that achieves better access, improved quality, and greater efficiency, particularly for society’s most vulnerable, including people of color, people with low income, and those who are uninsured.”[22] A noble mission, to be sure. Yet, perusal of the blogs on its website demonstrate that it embraces a pro-abortion ideology, apparently believing the unproven assumption that abortion improves the outcomes of the vulnerable women it professes to care for.[23]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG):

Similarly, in a recent issue, Obstetrics and Gynecology, the influential journal of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a peer-reviewed article, All-Cause Mortality in Reproductive-Aged Females by State: An Analysis of the Effects of Abortion Legislation,[24] as well as an editorial, Assessing the Effect of Abortion Restrictions Improving Methodology and Expanding Outcomes,[25] with both concluding, “An increasing number of laws restricting abortion was associated with increased maternal and infant mortality.” The article compared all-cause mortality in reproductive aged women, maternal mortality, infant mortality, and fetal mortality in states that have “supportive,” “moderate,” and “restrictive” legislation regarding induced abortion, as defined by the Guttmacher Institute.[26]

The legislative categories were determined based on the number of laws affecting abortion provision. It should be noted that prior to the Dobbs’ decision overturning Roe, bans on abortion were considered “unconstitutional,” so the only laws that could be enacted were relatively minor, addressing issues such as: in-person counseling, waiting periods, restrictions on insurance coverage, laws requiring “inaccurate or misleading counseling (such as information on medication abortion reversal or fetal personhood)”[27] , prohibition of telemedicine for chemical abortion, parental consent for minors, and laws placing safety requirements on abortion providers or clinics (so called TRAP [Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers] laws). The authors also considered the potential effect of trigger laws, or laws that would ban all abortions, although these laws were not implemented until after the Dobbs’ decision in mid-2022 and CDC mortality data from 2022 is not yet available. They did not describe their methodology for making these future predictions.

The states included in each category varied by time period, due to legislative changes over time, as Guttmacher examined abortion restrictions in the years 2000, 2010 and 2019, with the study authors comparing the number of restrictions to CDC mortality data from the same time periods. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality in reproductive-aged females, which they attempted to use as a proxy for maternal mortality because they acknowledged that “maternal mortality is unreliable in national data sets due to errors in recording and linking pregnancy events with death certificates.” However, they concluded that moderate and supportive states were not associated with a significant decrease in all-cause mortality compared with restrictive states.

Compared to abortion-restrictive states, they found the difference in maternal mortality in abortion-supportive states was not significantly different but was significantly lower in moderate states; infant mortality was significantly lower in both supportive and moderate states; and fetal mortality was significantly lower in moderate but not supportive states. It is interesting that they considered fetal mortality (death in-utero at greater than 20 weeks’ gestation) to be an endpoint, because the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) exempts fetal mortality due to induced abortion from its reporting requirements,[28] causing the true fetal death statistics to be considerably higher than the CDC reports. The CDC acknowledges that approximately 1% of U.S. abortions are performed at greater than 20 weeks gestation, leading to at least 6,299 additional fetal deaths occurring mostly in abortion-supportive states (based on 2019 CDC abortion statistics which undercount abortions because not all states report to the CDC).[29] Maternal mortality statistics were derived from the NCHS National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) reporting system, even though this system has been widely demonstrated to produce inaccurate and incomplete statistics.[30]

Bias: Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists portrays itself as representing physicians who care for women and their unborn children, it can be demonstrated that their leadership has a pro-abortion bias They have not surveyed their membership about whether they agree with ACOG’s abortion advocacy even though independent surveys demonstrate that only 7-14% of obstetricians will perform an abortion if requested by their patient.[31] In their 2014 Committee Opinion, Increasing access to abortion, ACOG stated, “Safe, legal abortion is a necessary component of women’s health care. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists supports the availability of high-quality reproductive health services for all women and is committed to improving access to abortion.” After decrying legislative restrictions on abortion, they added, “The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists calls for advocacy to oppose and overturn restrictions, improve access, and mainstream abortion as an integral component of women’s health care.”[32] Additionally, in their 2007 Committee Opinion, The limits of conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine, ACOG stated its members must violate their conscience if they are opposed to abortion, in that they “have the duty to refer patients in a timely manner to other providers if they do not feel they can in conscience provide the standard reproductive services their patients request.”[33]

American Medical Association (AMA):

As a third example, the American Medical Association (AMA)’s psychiatric journal published, Association Between State-Level Access to Reproductive Care and Suicide Rates Among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States, finding that “the enforcement of laws restricting access to abortion and reproductive care from 1974 to 2016 was associated with suicide rates among reproductive-aged women but not women of post-reproductive age, leading them to conclude, “Restrictions to reproductive care represent a macro-level risk factor for suicide among reproductive-aged women”. Their study design compared suicides in states enforcing at least one TRAP law to states without, finding a 5.81% higher suicide rate in reproductive aged women living in an abortion-restrictive state, although similar increases in suicides in post-reproductive aged women or deaths due to motor vehicle accidents were not seen. [34]

Bias: Unfortunately, abortion ideology also appears to motivate the American Medical Association. The AMA joined ACOG and other medical ideologues in abortion advocacy by cosigning an amicus brief in the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, in which they stated, “Reproductive health care is essential to women’s overall health. Access to abortion is an important component of reproductive health care.” Responding to the Dobbs decision, they decried the “egregious allowance of government intrusion into the medical examination room.”[35]

Investigating the assumptions:

These conclusions assume that lack of abortion causes maternal mortality, but there is no evidence for this conclusion, unless one assumes that by ending all pregnancies, one can end all the deaths associated with pregnancy. That fallacious reasoning would lead one to recommend prohibiting all cars to end deaths from motor vehicle accidents. Even so, it ignores the potential for maternal death following abortion, which is higher than commonly reported. In fact, the population most heavily affected by maternal mortality, Black women, who die in relation to pregnancy nearly three times as often as white and Hispanic women (53.3 Black deaths/100,000 live births vs 19.1 white deaths/100,000, 18.2 Hispanic deaths/100,000)[36], already have an abortion rate 3.7 times higher than white women.[37] Black women have both the highest maternal mortality ratios (MMR) and highest abortion rates. Both can’t be true if abortion reduces maternal mortality.

The conclusions of the above pro-abortion organizations ignore the scientific standard for determining causality, the Bradford-Hill criteria, which consists of: strength of association, consistency of data, specificity, temporality, dose-response, biologic plausibility, coherence, experimental evidence and analogy.[38] Immediately, “temporality” begs investigation. Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) determinations generally lag by several years due to the time it takes for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRC) to analyze death certificates and differentiate “pregnancy-associated” (the death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the end of pregnancy from any cause) from “pregnancy-related” deaths (the death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the end of pregnancy from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management).[39] The most recent CDC U.S. maternal mortality report published in 2022 analyzed data from 2017-2019.[40] The first state in recent years to enforce abortion restrictions was Texas on September 1, 2021. Many other states’ restrictions were not able to be enforced until after the Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022. One cannot argue that abortion restrictions implemented in 2021 and 2022 led to maternal mortality in 2017 through 2020, as each of these three biased organizations did.

The correlation of maternal mortality with lesser abortion limitations is disingenuous. One cannot make a plausible argument that minor abortion legislation such as informed consent requirements, facility or provider standards or insurance restrictions could possibly impact maternal mortality. The AMA’s research permitting only one such law in a state to meet the definition of “abortion restrictive” is even more spurious.

Could other factors that these states have in common contribute?

One might postulate that other state policies could contribute to a state’s MMR, but one cannot yet see into the future to know how abortion restrictions will affect the MMR. In general, abortion restrictive states have lower mean income and higher levels of poverty, which undoubtedly impacts MMR. According to the Commonwealth Fund, higher scores on a state’s “health equity scorecard”, demonstrating better function of state health care systems, correlates with improved outcomes. An argument can be made that better access to healthcare through state Medicaid expansion improves outcomes, but this is entirely unrelated to abortion access.

A further comparison is in order: Mississippi, one of the abortion restrictive states (and the originator of the Dobbs Supreme Court case), has one of the U.S.’ highest MMRs at 35.2/100,000 live births. However, some urban areas with extremely permissive abortion laws have similar ratios: Baltimore 35.2/100,000, Bronx County, NY 40.1/100,000, New York County, NY 25.8/100,000.[41] Since these populations have similarly poor maternal mortality but don’t share abortion restrictions, one must ask what they do have in common that may contribute to poor maternal outcomes. The answer, of course, is poverty. In Mississippi, 18.7% of the population lives in poverty, Baltimore City 20%, Bronx County 24.4%, and New York County 16.3%.[42]

As mentioned previously, the Commonwealth Fund report documented a higher maternal mortality ratio in abortion-restrictive states, but it also documented higher mortality in non-pregnant women of reproductive age and newborn children. Since non-pregnant women and newborn children do not have the opportunity to obtain an abortion to improve their mortality risk, it appears that there may be another factor or factors that predispose to death in these states that is unrelated to pregnancy.

The ACOG study examined similar parameters but did not document a consistent correlation. While they reported higher maternal mortality and fetal mortality in moderately restrictive states, they did not report a difference in states with permissive abortion. This data should challenge the assumption that widely available abortion reduces mortality, yet nonetheless, the biased authors drew just that conclusion. Although they did document significantly lower infant mortality in abortion permissive states, it is mind-boggling that they would use this data to promote abortion. If an unborn child manages to escape destruction in-utero, and has a lower risk of dying after birth, is that a reason to destroy more children before birth? Even if causation could be established (which is unlikely because there is no plausible explanation for abortion leading to reduced infant mortality), such an argument is heartless.

U.S. maternal mortality data is flawed:

It should be noted that the CDC has incomplete statistics regarding maternal mortality because most of their data is obtained from maternal death certificates, and maternal death certificates frequently do not document preceding pregnancies, especially early pregnancy events such as abortion or miscarriage.[43] Even if related to childbirth, at least 50% of maternal deaths are not reported as pregnancy-related on death certificates.[44] Mortality from events in the first half of pregnancy, which cannot be linked to a birth certificate, are even more difficult to detect, but high-quality records-linkage studies from Finland document that 73% of all maternal deaths and 94% of abortion-related deaths are not documented as such on the maternal death certificate.[45] Relying primarily on death certificate data as the CDC does, will inevitably undercount maternal deaths and is extremely unlikely to detect deaths subsequent to abortion.

Some have asserted that legal abortion is far safer than childbirth based on conjecture by researchers associated with the abortion industry. One misleading study making this claim used four disparate and difficult-to-calculate numbers with non-comparable denominators: abortion-related deaths were compared to the number of legal abortions and maternal deaths were compared to the number of live births.[46] Comparing a maternal mortality ratio to an abortion mortality rate is a meaningless exercise, even if all deaths following all pregnancy events were accurately recorded, which abundant data demonstrates is not the case. Since every abortion involves ending the life of an unborn human, abortion should never be recommended to a pregnant woman as a safer option than childbirth.

Clues for other contributors to maternal mortality:

Other statistics emphasized by the Commonwealth Fund report warrant mention. The 26 abortion-restrictive states accounted for 55% of U.S. births compared to the 24 permissive states accounting for 45% of U.S. births. Given that the U.S. Total Fertility Rate (TFR) has dropped dramatically from 3.7 (1960) to 1.6 (2020), with 2.1 considered replacement TFR,[47] the restrictive states (even prior to the implementation of the restrictions) were having more children, which arguably will benefit the state (and the U.S. as a whole), because a young demographic provides a boost to the economy through more workers and consumers. These states will continue to experience a fertility benefit as the abortion-restrictions allow more children to be born.

One further possible explanation for the disparity in maternal mortality documented in the Commonwealth Fund Report is that in abortion-restrictive states, 39% of counties were “maternity care deserts,” defined as having “limited or no access to maternity health care services” compared to 25% of counties in permissive states. A look at a map helps to explain this – many of the restrictive states are in less densely populated areas of the country, the south and Midwest, whereas more people live in urban areas with easier access to obstetric care in permissive states. A 2015 analysis by Scientific American demonstrated that MMR is higher in rural areas at 29.4 deaths/100,000 live births vs 18.2/100,000 in urban areas.[48] The solution, of course, to the problem of “maternity care deserts” is for states to prioritize recruiting health care workers to rural areas, supporting rural hospitals, and facilitating transfer agreements when a higher level of care is needed in emergencies. Seventeen percent of births in restrictive states occur in rural areas compared to only 8% in permissive states. The answer to the increased MMR in abortion-restrictive states is not to promote ending the lives of unborn rural children. Women and families in rural areas need improved access to safe obstetric care.

The Commonwealth Fund concluded, “Compared with their counterparts in other states, women of reproductive age and birthing people in states with current or proposed abortion bans have more limited access to affordable health insurance coverage, worse health outcomes, and lower access to maternity care providers. Making abortion illegal risks widening these disparities, as states with already limited Medicaid maternity coverage and fewer maternity care resources lose providers who are reluctant to practice in states that they perceive as restricting their practice.” A physician who represents the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) expressed concern that areas with decreased access to abortion will cause prenatal centers to be “overwhelmed with patients and that may create delays in care.”[49]

Although the first sentence in their conclusion follows from the evidence, as discussed above, the second sentence is a non sequitur and cannot be derived from their data. This statement demonstrates pro-abortion ideology, rather than scientific inference. Although many in the medical profession profess a pro-choice preference, only 7-14% of obstetricians polled say they would perform an elective abortion if requested by a patient.[50] Restricting abortion will in no way affect the care provided by most obstetricians, as most do not perform elective abortions, and it is unlikely that the restrictions will cause obstetricians to become reluctant to practice in these states. In fact, the opposite is likely to be the case, as the births of more babies will give obstetricians more opportunities to practice their profession. The ACOG representative’s concern that prenatal centers will be overwhelmed can and should be addressed by recruiting more health care professionals and expanding birthing centers. In no other industry is the solution to growth getting rid of the customers.

The Commonwealth Fund then offers a better solution, “States have it within their power to avoid that outcome. In partnership with health plans, providers, and residents, state leaders could attempt to recruit more maternity care providers — including midwives, physicians, doulas, and nurses — and promote the operation of more birthing facilities, such as hospital units and birthing centers.” It is unclear why Commonwealth decided to present their data in the context of abortion rather than simply advocating for needed health care access on which there is broad public consensus and benefit.

Many mothers need financial assistance to deliver their children and it is well documented that access to prenatal care improves maternal and infant outcomes. Government funded Medicaid accounts for 42% of payments for childbirth in the U.S.[51] Medicaid expansion from two months to one year after delivery has been adopted by 31 states.[52] Yet we see that even this discussion is influenced by politics. Texas, for example, did not expand Medicaid with implementation of the Affordable Care Act, but created a similar program with state funds, Healthy Texas Women, which provided additional health care coverage for Medicaid funded mothers until a year after birth. Recently, however, Texas applied to the federal government to expand Medicaid coverage until six months postpartum, but this request was denied by the Biden administration in what can only be seen as a punitive and political move.[53]

How are abortion restrictions related to suicide?

The American Medical Association’s article documented that women who live in states with abortion restrictions are more likely to commit suicide and concluded that inability to obtain abortion or barriers to abortion access were to blame. Again, failure to examine other contributing factors to suicide (such as poverty, relationship breakdown or incidence of mental health disorders) points toward a political motivation to reach this conclusion.

What do better quality studies addressing this premise show about the link between abortion and mental health complications? Numerous studies demonstrate that abortion is linked to mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse or overdose, excessive risk-taking behavior, self-harm and suicide,[54] all of which have increasingly been shown to contribute to maternal mortality. High quality international records-linkage studies demonstrate the risk of death after abortion compared to childbirth from any violent cause is six times higher, suicide six to seven times higher, accidental death four to five times higher, and death by homicide 10 to 14 times higher.[55] Some subpopulations are at increased risk of mental health harm after abortion, such as those who have a later abortion, abort at a young age, abort a desired pregnancy, have multiple abortions or have a prior history of mental illness.[56] Conversely, delivery of a new baby often leads a woman to reduce her risk of accidents by staying at home to care for her new child, demonstrating that childbirth is protective rather than harmful for most women. The AMA’s article fails to articulate a plausible mechanism for how limiting access to abortion could worsen a woman’s risk for suicide in the face of these well-documented facts.

What are the common causes and contributing factors of maternal mortality?

Although most people assume maternal mortality refers to catastrophic events during childbirth, it should be noted that only one-quarter of maternal deaths occur on the day of delivery or within the first week. Twenty-two percent occur during pregnancy, and more than half (53%) between one week and one year after delivery. Mental health related deaths are the leading cause (23%), followed by hemorrhage (14%), cardiac conditions (13%), infection (9%), thrombotic embolism/blood clot (9%), cardiomyopathy (9%) and hypertension (7%).[57]

As mentioned earlier, Black women have nearly three times the MMR of white women, with conversation often limited to suggesting institutional factors of systemic racism. Yet, in a military study that controlled for social factors such as economics and health care access, Black women receiving the same health care as white women were still 2.8 times as likely to be admitted to an intensive care unit and 1.7 times as likely to experience severe maternal morbidity compared to white women.[58] We must fully explore other potentially contributing factors as we strive to understand the disparities.

It is important to note that the outcomes of pregnancy differ among races. Spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) rates are similar among all groups, approximately 10-20%.[59] The rates of induced abortion vary dramatically, however, affecting 34% of the pregnancies in Black women but only 11% in white women. Abortions after the first trimester, which are more dangerous, are also more common in the Black population, accounting for 13% of abortions among Black women compared to 9% among white women. As a result of these factors, only 48% of pregnancies among the Black population result in childbirth as compared to 65% of pregnancies among the white population.[60] Since the number of live births is used as the denominator in maternal mortality calculations, the maternal mortality ratio is artificially elevated in Black women.

Preconceptual health risk factors impact maternal mortality and differ by race. Obesity affects 47% of the Black population and 47% of the Hispanic population, but only 38% of the white population.[61] Hypertension affects 40% of the Black population, but only 26% of the Hispanic population and 27% of the white population.[62] Diabetes affects 13% of the Black population and 12% of the Hispanic population, but only 7% of the white population.[63] An inherited thrombophilia will increase the propensity to form blood clots that block blood vessels, and this occurs more commonly in the Black population.[64] These preconceptual factors may directly predispose to mortality due to disease-related complications, and they are also associated with early delivery and increased cesarean section rates, which indirectly raise mortality risk. Chronic hypertension may lead to preeclampsia or eclampsia, which accounts for 11.4% of deaths in Black women, but only 6.5% of deaths in white women.[65]

Poverty is a risk factor for failure to obtain appropriate medical care and may contribute to the racial disparity noted in maternal mortality. Poverty is also associated with the preconceptual health risk factors mentioned above: obesity, hypertension and diabetes. In 2021, 19.5 percent of the Black population live in poverty compared to 17.1 percent of Hispanics and ten percent of white women.[66] Only five percent of married couples live in poverty, so the high rates of childbirth to unmarried women in minority populations may be associated with their increased incidence of living in poverty. Unmarried birth occurs in 67% of Black women, 39% of Hispanic women, and 27% of white women.[67] But independent of financial status, giving birth and caring for a child without a partner places a woman at an obvious disadvantage. If she should become ill, she may not seek timely emergency care due to lack of social support, childcare, or transportation.

It is possible the narrative that abortion and childbirth are “a woman’s choice” may negatively impact the social status of women who choose to carry a pregnancy to birth. Although it requires a woman and man to create a child, society’s relegation of the responsibility for continuing the pregnancy to a woman seems to have left many men disenfranchised, resulting in many absent fathers if a woman chooses to give birth to her child. This increases the odds that she lives in poverty as a single mother. Thus, we have seen a dramatic increase in the number of unmarried mothers since abortion was legalized, from 11% in 1970 to 40% in 2016, disproportionately affecting Black mothers.

SUMMARY OF HOW ABORTION RESTRICTIONS IMPACT MATERNAL HEALTH

- Abortion restrictions will not prohibit medical interventions for maternal life-threatening emergencies.

- Limiting abortion will prevent many vulnerable women from being exposed to the increased risk of death in the year following abortion.

- Abortion restrictions will limit later abortions which are more dangerous for a woman.

- Abortion restrictions will reduce the incidence of repeat abortions.

- Abortion restrictions will prevent future mental health disorders in some women.

- Abortion restrictions will prevent some future pregnancy complications.

- Abortion restrictions may also lead to more fathers taking responsibility for their children and decrease the rates of single motherhood.

- Many of the states that have implemented abortion restrictions have prioritized expanding a broad social support net to meet the needs of a pregnant mother, which is likely to improve maternal mortality.

- Abortion restrictions are unlikely to result in instrumental “coat-hanger” septic abortions.

- Abortion restrictions will encourage both men and women to change their sexual behavior and use more reliable contraception.

- Abortion restrictions will also reduce unwanted abortions.

- Abortion restrictions have not been shown to increase maternal mortality ratios in other countries.

CONCLUSION:

The collection of data pertaining to U.S. maternal mortality is complicated and etiologies leading to maternal deaths are often poorly understood. Politicization of the issues of maternal mortality and induced abortion have led to ideologically driven recommendations. We should think long and hard before doubling down on more abortions as the solution to the complex and heartbreaking problem of maternal mortality. Dishonestly attributing state abortion restrictions as reasons for high maternal mortality, as the Commonwealth Fund, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association have attempted, directs attention away from the true etiologies of the devastating problems of maternal mortality and female suicides. For the reasons mentioned above, it is likely that abortion restrictions will improve, rather than worsen, the problems of maternal mortality and female suicides in the states that have chosen to protect unborn life.

Ingrid Skop, M.D., F.A.C.O.G., is Senior Fellow and Director of Medical Affairs at Charlotte Lozier Institute.

[1] Jerman J, Jones RK, Onda T. Characteristics of U.S. abortion patients in 2014 and changes since 2008. Guttmacher Institute; Agency for Health Care Administration, “Reported Induced terminations of Pregnancy (ITOP) by Reason, by Trimester, 2021 – Year to Date,” https://ahca.myflorida.com/MCHQ/Central Services/Training Support/docs/TrimesterByReason 2021.pdf, accessed December 21, 2022.

[2] Reardon DC, Ney PG, Scheuren F, Cougle J, Coleman PK, Strahan TW. Deaths associated with pregnancy outcome: a record linkage study of low-income women. South Med J 2002;95:834-841; Gissler M, Hemminki E, Lonnqvist J. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-94. Register linkage study. Br Med J 1996;313:1431-1434; Karalis E, Ulander V, Tapper A, Gissler M. Decreasing mortality during pregnancy and for a year after while mortality after termination of pregnancy remains high: a population-based register study of pregnancy associated deaths in Finland 2001-2012. BJOG 2017;124:1115-1121; Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Collie M, Buekens P. Injury deaths, suicides and homicides associated with pregnancy, Finland 1987-2000. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:459-463; Gissler M, Kaupilla R, Merilainen J, Toukomaa H, Hemminki E. Pregnancy-associated deaths in Finland, 1987–1994—definition problems and benefits of record linkage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:651-657; Reardon DC, Coleman PK. Short and long term mortality rates associated with first pregnancy outcome: Population register based study for Denmark 1980-2004. Med Sci Monit 2012;18(9):71–76; Coleman PK, Reardon DC, Calhoun B. Reproductive History Patterns and Long-term Mortality Rates: A Danish population-based record linkage study. Eur J of Public Health.

[3] Kortsmit K, Nguyen AT, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ 2022;71(No. SS-10):1–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7110a1. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/ss/ss7110a1.htm, accessed January 25, 2023.

[4] ACOG. Practice Bulletin 135: Second Trimester Abortion. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121(6):1394-1406; Bartlett, Berg, et al, Risk Factors for Legal Induced Abortion Related Mortality in the U.S. OBG. 2004;103:(4)729-737; Zane, Creanga, et al. Abortion Related Mortality in the U.S.:1998-2010. OBG. 2015;126:(2)258-265.

[5] Bartlett, Berg, et al, Risk Factors for Legal Induced Abortion Related Mortality in the U.S. OBG. 2004;103:(4)729-737.

[6] Reardon DC and Thorp JM Pregnancy associated death in record linkage studies relative to delivery, termination of pregnancy, and natural losses: A systematic review with a narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Medicine. 2017;5:1-17.

[7] Gissler M, Kauppila R, Merilainen J, et al. Pregnancy Associated Deaths in Finland 1987-1994. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1997;76:651-657; Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Injury deaths, suicides and homicides associated with pregnancy, Finland 1987-2000. Eur J of Public Health. 2005;15(5):459-463; Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Pregnancy Associated Mortality After Birth, Spontaneous Abortion or Induced Abortion in Finland. 1987-2000. American Journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(2):422-427; Gissler M, Berg C, et al. Methods of Identifying Pregnancy Related Deaths: Population Based Data From Finland. 1987-2000. Pediatrics and Perinatology Epidemiology. 2004;18(6):448-55; Gissler M, et al. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-94. Register linkage study. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:14311434.

[8] Heather J Baldwin, Jillian A Patterson, Tanya A Nippita, Siranda Torvaldsen, Ibinabo Ibiebele, Judy M Simpson, Jane B Ford. Antecedents of Abnormally Invasive Placenta in Primiparous Women: Risk Associated With Gynecologic Procedures. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:227-233; Mogos, M. F., J. L. Salemi, M. Ashley, V. E. Whiteman, and H. M. Salihu. 2016. “Recent Trends in Placenta Accreta in the United States and Its Impact on Maternal-fetal Morbidity and Healthcare-associated Costs, 1998-2011.” Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 29:1077.

[9] American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Guideline 5. The Association between surgical abortion and preterm birth: An Overview. Available at https://aaplog.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/PB-5-Overview-of-Abortion-and-PTB.pdf. Accessed August 1, 2022; Swingle, et al. Abortion and the Risk of Subsequent Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. (2009)54:95-108; Liao, et al. Repeated medical abortions and the risk of preterm birth in the subsequent pregnancy. Arch Gyn Ob 2011;284:579-586.

[10] National Fatherhood Initiative. The proof is in: Father absence harms children. Available at https://www.fatherhood.org/father-absence-statistic.

[11] Rapid response to Bernard Nathanson. Available at https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/03/how-abortion-movement-started-deceit-and-lies-dr-nathanson, accessed November 4, 2022; Planned Parenthood’s false stat. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/05/29/planned-parenthoods-false-stat-thousands-women-died-every-year-before-roe/, accessed November 4, 2022.

[12] CDC Abortion Surveillance Summaries. Available at www.stacks.cdc.gov, accessed August 8, 2022

[13] Calderone D. Illegal abortion as a public health problem. AJ of Public Health. 1960;50:949.

[14] Levine P. Sex and Consequences: Abortion, Public Policy, and the Economics of Fertility. (Princeton University Press. 2004.) p 107-132.

[15] Rue VM, Coleman PK, Rue JJ, Reardon DC. Induced abortion and traumatic stress: A preliminary comparison of American and Russian women Med Sci Monit 2004; 10(10): SR5-16; Reardon D, Longbons T. Effects of Pressure to Abort on Women’s Emotional Responses and Mental Health. Cureus 15(1): e34456. doi:10.7759/cureus.34456.

[16] Reardon DC The Abortion and Mental Health Controversy: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Common Ground Agreements, Disagreements, Actionable Recommendations, and Research Opportunities. SAGE Open Medicine 6, 2018, 205031211880762.

[17] Maternal mortality and maternity care in the United States compared to 10 other developed countries. November 18, 2020. Commonwealth Fund. Available at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries, accessed August 31, 2022.

[18] Koch E, Thorp J, Bravo M, et al. Women’s educational level, maternal health facilities, abortion legislation and maternal deaths: A natural experiment in Chile from 1957-2007. PlosOne 2012;7(5):1-16; Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M,et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet 2010; 375: 1609–23.

[19] Confidential maternal death enquiry in Ireland. 2016-2018. Available at https://www.ucc.ie/en/media/research/maternaldeathenquiryireland/ConfidentialMaternalDeathEnquiryReport2016%C3%A2%C2%80%C2%932018.pdf, accessed August 29, 2022; Notifications in accordance with section 20 of the protection of life during pregnancy act 2013. Available at https://assets.gov.ie/19420/c9bc493cb2274e098e28f3ba59067ba0.pdf, accessed August 29, 2022; Abortion statistics: England and Wales 2018. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/808556/Abortion_Statistics__England_and_Wales_2018__1_.pdf, accessed August 29, 2022.

[20] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2022/dec/us-maternal-health-divide-limited-services-worse-outcomes, accessed December 20, 2022.

[21] Howard J. Maternal and infant death rates are higher in states that ban or restrict abortion, report says. CNN December 14, 2022. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/14/health/maternal-infant-death-abortion-access/index.html, accessed December 20, 2022; Madani D. States with more abortion restrictions have higher maternal and infant mortality, report finds. NBC News. Available at https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/abortion-restrictions-higher-maternal-infant-mortality-rcna61585, accessed December 20, 2022.

[22] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/about-us, accessed December 20, 2022.

[23] https://www.commonwealthfund.org/search?search_api_fulltext=abortion, accessed December 20, 2022.

[24] Harper LM, Leach JM, Robbins L, et al. All-Cause Mortality in Reproductive-Aged Females by State: An Analysis of the Effects of Abortion Legislation. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(2):236-242.

[25] Darney BG, et al. Assessing the Effect of Abortion Restrictions: Improving Methodology and Expanding Outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(2):233-235.

[26] Available at https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/08/state-abortion-policy-landscape-hostile-supportive, accessed February 3, 2023.

[27] This is the author’s terminology.

[28] National Center for Health Statistics. State Definitions and Reporting Requirements for Live Births, Fetal Deaths, and Induced Terminations of pregnancy. Hyattsville (MD) NCHS; 1997. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/other/miscpub/statereq.htm, accessed February 6, 2023.

[29] Kortsmit K, Mandel MG, Reeves JA, et al. Abortion Surveillance – United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ 2021;70(No. SS-9):1-29. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/ss7009a1.htm, accessed August 8, 2022.

[30] Physicians’ Handbook on Medical Certification of Death. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003 Revision. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf, accessed July 20, 2022; Brantley, MD, Callaghan W, Cornell A, et al. 2018. Building U.S. Capacity to Review and Prevent Maternal Deaths: Report from Nine Maternal Mortality Review Committees. MMRIA. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://www.cdcfoundation.org/sites/default/files/files/ReportfromNineMMRCs.pdf, accessed August 7, 2022; St. Pierre A, et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Identifying, Reviewing, and Preventing Maternal Deaths. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:138–42.

[31] Desai S, Jones R, Castle K. Estimating abortion provision and abortion referrals among United States obstetricians and gynecologists in private practice. Contraception 2018;97:297-302; Stuhlberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(3):609-614.

[32] Increasing access to abortion. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 613. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:1060–5.

[33] The limits of conscientious refusal in reproductive medicine. ACOG Committee Opinion No 385. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:1203-1208.

[34] Zandberg J, Waller R, Visoki E, et al. Association Between State-Level Access to Reproductive Care and Suicide Rates Among Women of Reproductive Age in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online December 28, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.4394.

[35] Available at https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/leading-medical-groups-file-amicus-brief-dobbs-v-jackson, accessed February 5, 2023.

[36] National Center for Health Statistics, Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020.

[37] Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program. Available at https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2020/demo/saipe/2020-state-and-county.html, accessed August 22, 2022.

[38] UNC Causality. Available at https://sph.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/112/2015/07/nciph_ERIC15.pdf, accessed December 20, 2022.

[39] Trost SL, Beauregard J, Njie F, et al. Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US states, 2017-2019. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2022.

[40] CDC press release. September 19, 2022: Four in 5 pregnancy-related deaths in U.S. are preventable. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/p0919-pregnancy-related-deaths.html#print, accessed December 20, 2022.

[41] Calculations utilizing 2014-2020 birth data from Centers for Disease Control and Preventions, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Natality on CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the Natality Records 2007-2021, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-current.html on Feb 15, 2023 9:37:47 AM. Death data for 2014-2020 is from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Feb 15, 2023 9:41:54 AM.

[42] Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) Program. Available at https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2020/demo/saipe/2020-state-and-county.html, accessed August 22, 2022.

[43] Studnicki J, et al. Improving the Metrics and Data Reporting for Maternal Mortality: A Challenge to Public Health Surveillance and Effective Prevention. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2019;11(2):e17; Marmion P, Skop I. Induced abortion and the increased risk of maternal mortality. The Linacre Quarterly. 2020;87(3):302-310; Jatlaoui TC, Boutot ME, Mandel MG, et al. Abortion Surveillance-United States 2015. Surveillance Summaries. 2018;67(13);1–45, accessed August 1, 2022.

[44] Horon IL. Underreporting of Maternal Deaths on Death Certificates and the Magnitude of the Problem of Maternal Mortality. AJ of Public Health. 2005;95:478-82; Deneux-Tharaux C, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Underreporting of pregnancy related mortality in the U.S. and Europe. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(4):684-692.

[45] Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, Buekens F. Methods for identifying pregnancy associated deaths: Population based data from Finland 1987-2000. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2004;18:448-455. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00591.x; Gissler M, Berg C, et al, Pregnancy Associated Mortality After Birth, Spontaneous Abortion or Induced Abortion in Finland. 1987-2000. AJOG 2004;190:422-427.

[46] Raymond EG, Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:215–9; David A Grimes. https://www.huffpost.com/author/david-a-grimes, accessed December 9, 2022.

[47] Fertility rate, total (births per women)-United States. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=US, accessed December 21, 2022.

[48] Maron DF. Maternal Health Care Is Disappearing in Rural America. Scientific American February 15, 2017. Available at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/maternal-health-care-is-disappearing-in-rural-america/#:~:text=Scientific%20American%20analyzed%20public%20mortality,why%20this%20happens%20is%20unclear, accessed December 20, 2022.

[49] Howard, Maternal and infant death rates, https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/14/health/maternal-infant-death-abortion-access/index.html.

[50] Desai S, Jones R, Castle K. Estimating abortion provision and abortion referrals among United States obstetricians and gynecologists in private practice. Contraception 2018;97:297-302; Stuhlberg DB, Dude AM, Dahlquist I, Curlin FA. Abortion provision among practicing obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(3):609-614.

[51] Kaiser Family Foundation. Births Financed by Medicaid (2020). https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D, accessed January 24, 2023.

[52] https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/, accessed February 27, 2023.

[53] https://thetexan.news/biden-administration-signals-rejection-of-texas-postpartum-health-care-extension-state-officials-push-back/#:~:text=Austin%2C%20TX%2C%20August%2012%2C,bipartisan%20array%20of%20state%20officials, accessed December 20, 2022.

[54] Reardon D. The abortion and mental health controversy: A comprehensive literature review of common ground agreements, disagreements, actionable recommendations, and research opportunities. Sage Open Medicine. 2018:6:1-38; Coleman PK, et al. Women who suffered emotionally from abortion: a qualitative synthesis of their experiences. J of American Physicians and Surgeons. 2017;22(4):113-118.

[55] Gissler M, Hemminki E, Lonnqvist J. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-94. Register linkage study. Br Med J 1996;313:1431-1434; Karalis E, Ulander V, Tapper A, Gissler M. Decreasing mortality during pregnancy and for a year after while mortality after termination of pregnancy remains high: a population-based register study of pregnancy associated deaths in Finland 2001-2012. BJOG 2017;124:1115-1121; Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Collie M, Buekens P. Injury deaths, suicides and homicides associated with pregnancy, Finland 1987-2000. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:459-463; Gissler M, Kaupilla R, Merilainen J, Toukomaa H, Hemminki E. Pregnancy-associated deaths in Finland, 1987–1994—definition problems and benefits of record linkage. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:651-657.

[56] Major B, Appelbaum M, Beckman L, et al. American Psychological Association, Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion. (2008). Report of the Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/wpo/mental-health-abortion-report.pdf, accessed August 1, 2022.

[57] CDC press release. September 19, 2022: Four in 5 pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. are preventable. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2022/p0919-pregnancy-related-deaths.html#print, accessed December 20, 2022.

[58] Hamilton JL, Shumbusho D, Cooper D, et al. Race matters: Maternal morbidity in the Military Health System. American Journal of Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(5):512e1-6.

[59] https://www.marchofdimes.org/find-support/topics/miscarriage-loss-grief/miscarriage.

[60] Studnicki J, et al. Improving the Metrics and Data Reporting for Maternal Mortality: A Challenge to Public Health Surveillance and Effective Prevention. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2019;11(2):e17.

[61] Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, and Ogden CL. “Prevalence of Obesity among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016.” NCHS Data Brief 2017;188:1–8.

[62] CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension—United States, 2003–2010.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2013;62:351–55.

[63] CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html, accessed August 7, 2022.

[64] Phillip C. Differences in thrombotic risk factors in black and white women with adverse pregnancy outcome. Thromb. Res. 2014;133(1)108-111.

[65] Davis NL, Smoots AN, Goodman DA. Pregnancy-related deaths: Data from 14 U.S. Maternal Mortality Review Committees, 2008-2017. Atlanta GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/mmr-data-brief_2019-h.pdf, accessed August 7, 2022.

[66] “Poverty in Black America,” Black Demographics. Available at http://blackdemographics.com/households/poverty/, accessed August 7, 2022.

[67] Dramatic increase in the outside of marriage in the United States from 1990 to 2016. Available at https://www.childtrends.org/publications/dramatic-increase-in-percentage-of-births-outside-marriage-among-whites-hispanics-and-women-with-higher-education-levels, accessed August 7, 2022.