The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2019—Ten Things You Need to Know About H.R. 2975

This is Issue 39 in the On Point Series.

The views expressed in this paper are attributable to the author and do not necessarily represent the position of the Charlotte Lozier Institute. Nothing in the content of this paper is intended to support or oppose the progress of any bill before the U.S. Congress.

The full text of this publication can be found at: https://lozierinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/The-Women’s-Health-Protection-Act-of-2019—Ten-Things-You-Need-to-Know-About-H.R.-2975.pdf

Comments and information requests can be directed to:

Charlotte Lozier Institute

E-mail: [email protected]

Ph. 202-223-8073/www.lozierinstitute.org

- H.R. 2975 would impose a heightened burden of proof on many if not most if not all abortion laws ever enacted 2

- H.R. 2975 treats abortion like one more “medical procedure”—not like the “unique act” and “grave decision” it really is 4

- H.R. 2975 excludes important legislative interests that the Supreme Court has expressly recognized 5

- Under H.R. 2975 doctors and nurses who conscientiously object to abortion could lose their jobs and Catholic hospitals could lose public funds. 7

- H.R. 2975 would jeopardize limits on taxpayer-funded abortion—including the Hyde Amendment 9

- H.R. 2975 would jeopardize parental notice requirements. 11

- H.R. 2975 would jeopardize informed consent laws such as ultrasound requirements and reflection periods 13

- H.R. 2975 would block States from protecting pain-capable babies at 20 weeks of pregnancy in most cases 15

- H.R. 2975 would force States to allow discrimination. 16

- H.R. 2975 would make it harder to limit late abortions 17

On May 23, 2019 U.S. Rep. Judy Chu (D-CA-27) introduced H.R. 2975, titled the “Women’s Health Protection Act of 2019,” in the U.S. House of Representatives.

On the same day U.S. Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduced S. 1645, with the same title, in the U.S. Senate.

This paper discusses H.R. 2975. However, according to the Congressional Research Service, as reported at congress.gov, H.R. 2975 and S. 1645 are “identical bills.”

As of February 6, 2020, according to congress.gov, 215 lawmakers have cosponsored the House bill and 42 lawmakers have cosponsored the Senate bill.

No Republican lawmaker has sponsored or cosponsored either the House or Senate bill except for Rep. Jefferson Van Drew (NJ-2) who cosponsored the House bill as a Democrat before joining the Republican Party.

The stated purpose of the Women’s Health Protection Act of 2019 is to protect the ability to perform and obtain abortions.

H.R. 2975 would supersede and apply to all Federal law notwithstanding any other provision of Federal law, including the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993.

H.R. 2975 would also trump any State law that conflicts with H.R. 2975.

An earlier version of the legislation, introduced in the 113th Congress, was described by one lawmaker’s office as the “Abortion On Demand Act.”[1]

H.R. 2975 is premised on the belief that abortion is “essential” to women’s health and “central” to women’s ability to “participate equally” in the economic and social life of the United States.

According to H.R. 2975, “[n]ot all people who become pregnant or need abortion services identify as women.”

H.R. 2975 cites a study said to find that “the biggest threats” to the “quality” of abortion services in the United States come from “State regulations that creates barriers to care,” undoubtedly a reference to pro-life legislation. H.R. 2975 makes no reference to Kermit Gosnell, James Pendergraft, or George Klopfer.

In a challenge brought under H.R. 2975, State governments that defend pro-life laws and lose must pay litigation costs and “reasonable attorney fees” to the pro-abortion plaintiffs. If the pro-abortion plaintiffs lose, they are protected from paying litigation costs and reasonable attorney fees unless their action is deemed frivolous.

H.R. 2975 would impose a heightened burden of proof on many if not most if not all abortion laws ever enacted

Section 4(b)(2) of H.R. 2975 would make certain pro-life policies unlawful unless, as set forth in Section 4(d), the government “establish[es], by clear and convincing evidence,” that the policy “significantly advances” in the least restrictive way either the “safety of abortion services” or the “health of patients.”

According to the pro-abortion Guttmacher Institute, the “clear and convincing evidence” test is an “unusually strict”[2] legal standard.

Plaintiffs such as Planned Parenthood could trigger this heightened burden of proof by establishing a claim under Section 4(b)(2). Section 4(b)(2) creates a statutory right to perform or obtain abortion services “without a limitation or requirement” that both

- “singles out” the provision of abortion services

- and “impedes access to abortion services based on one or more of the factors” described in Section 4(c).

H.R. 2975 does not define the term “singles out” but does instruct courts to “liberally construe” provisions of H.R. 2975 to “effectuate” its purposes, thus opening the door to an expansive, permissive interpretation. Courts could interpret “singles out” to include any law that specifically addresses the subject of abortion either by itself or with one or more other subjects even if merely applying a general standard to a matter involving abortion but doing so in a manner that addresses abortion specifically. This interpretation would encompass a massive swath of abortion-related regulation—if not the entire field.

As to the second element of Section 4(b)(2), the factors set out in Section 4(c) include:

- “Whether the limitation or requirement interferes with a health care provider’s ability to provide care and render services in accordance with the provider’s good-faith medical judgment.”

- “Whether the limitation or requirement is reasonably likely to delay some patients in accessing abortion services.”

- “Whether the limitation or requirement is reasonably likely to directly or indirectly increase the cost of providing abortion services or the cost for obtaining abortion services (including costs associated with travel, childcare, or time off work).”

- “Whether the limitation or requirement is reasonably likely to have the effect of necessitating a trip to the offices of a health care provider that would not otherwise be required.”

- “Whether the limitation or requirement is reasonably likely to result in a decrease in the availability of abortion services in a given State or geographic region.”

The potential scope of regulation covered by these factors would be enormous. In particular, two of the Section 4(c) factors, Section 4(c)(1) and Section 4(c)(3), are so broadly worded that they could be interpreted to reach a massive swath of abortion-related regulation—if not the entire field. Even when limited to situations satisfying the “singles out” requirement in section (4)(b)(2)(A), these provisions provide astonishing “trump cards” for abortionists to challenge a host of abortion regulations based on potentially nothing more than the additional assertion that the regulation “interferes” with the abortionist’s ability to “render services” in accordance with their “good-faith medical judgment” or would be “reasonably likely” to increase, “directly or indirectly,” the cost of providing or obtaining an abortion. At a minimum these provisions would provide a statutory basis for generating a huge amount of litigation.

H.R. 2975 treats abortion like one more “medical procedure”—not like the “unique act” and “grave decision” it really is

“The rationality of distinguishing between abortion services and other medical services when regulating physicians or women’s healthcare has long been acknowledged by Supreme Court precedent.”[3]

H.R. 2975, in contrast, treats abortion like one more “medical procedure” subject only to health and safety considerations. In at least two instances H.R. 2975 invokes the concept of procedures that are “medically comparable” to abortion. Elsewhere H.R. 2975 puts abortion in the context of procedures such as “hysteroscopies,” “loop electrosurgical excision procedures,” “sigmoidoscopy,” and “colonoscopy.”

H.R. 2975 ignores the reality that abortion is a “unique act”[4] and a “grave decision”[5] that “has implications far broader than those associated with most other kinds of medical treatment.”[6]

In the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, “Abortion is inherently different from other medical procedures, because no other procedure involves the purposeful termination of a potential life.”[7]

In cases involving “colonoscopy” and “loop electrosurgical excision procedures” no woman “come[s] to regret [her] choice to abort the infant life [she] once created and sustained.”[8]

H.R. 2975 discredits itself by discrediting the distinction between abortion and other “medical procedures.”

“Whether to have an abortion requires a difficult and painful moral decision.”[9] Whether to have a sigmoidoscopy does not.

H.R. 2975 excludes important legislative interests that the Supreme Court has expressly recognized

Section 4(b)(2) imposes a standard of heightened scrutiny that can be overcome only by showing that the regulation in question “significantly advances” in the least restrictive way at least one of the only two interests recognized by the provision: “the safety of abortion services” and “the health of patients.”

The Supreme Court has certainly recognized the government interest in maternal health. But the Court has also recognized additional legislative interests in the abortion context including

- the “State’s interest in respect for life,”[10]

- “the State’s interest in promoting respect for human life at all stages in the pregnancy,”[11]

- “the legitimate interest of the Government in protecting the life of the fetus that may become a child,”[12]

- the governmental “‘interest in protecting the integrity and ethics of the medical profession,’”[13]

- the State’s “legitimate interests in regulating the medical profession in order to promote respect for life, including life of the unborn,”[14]

- “the legitimate purpose of reducing the risk that a woman may elect an abortion, only to discover later, with devastating psychological consequences, that her decision was not fully informed,”[15]

- the State’s “legitimate concern” about “lack of information concerning the way in which the fetus will be killed” and “interest in ensuring so grave a choice is well informed,”[16]

- and “the state’s interests in the well-being of the immature minor . . . and in the integrity of the family.”[17]

In time, governments have also come to identify new interests in the abortion context such as protecting unborn children at the time they can feel pain and protecting unborn children from discrimination based on sex, race, or disability.

H.R. 2975 excludes from its scope the Federal ban on partial-birth abortions and allows for, at least theoretically, some post-viability limits on abortion. However, in imposing a standard of heightened scrutiny under Section 4(b)(2), H.R. 2975 recognizes only “health” and “safety” as legitimate legislative concerns. This narrow focus reveals H.R. 2975 as an extreme, blinkered, ideological piece of legislation.

Under H.R. 2975 doctors and nurses who conscientiously object to abortion could lose their jobs and Catholic hospitals could lose public funds

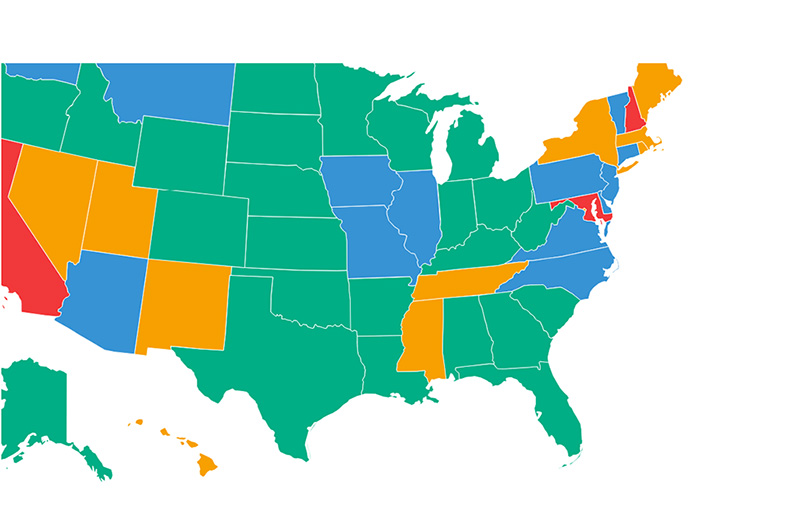

According to the law professor and religious freedom expert Mark Rienzi, “virtually every state in the country has some sort of statute protecting individuals and, in many cases, entities who refuse to provide abortions” and “[s]ome states expressly limit this protection to the practice of abortion, which is treated specially.”[18]

Federal law also provides protections to individuals and institutions that object to performing abortions.[19]

H.R. 2975 poses a grave risk to those vital protections. Under H.R. 2975, doctors and nurses who conscientiously refuse to participate in abortion could lose their jobs and Catholic and other religious hospitals could be forced to provide abortions or lose public funds.

Section 4(a)(10) creates a statutory right to provide an abortion without any limitation “on a health care provider’s ability to provide immediate abortion services when that health care provider believes, based on the good-faith medical judgment of the provider, that delay would pose a risk to the patient’s health.”

As defined in Section 3(2), the term “health care provider” includes entities as well as individuals.

Laws that prohibit hospitals and other entities from discriminating against doctors and nurses who conscientiously refuse to participate in abortion would fail under H.R. 2975 if the entity health care provider could show that such laws limit its ability to provide “immediate” abortion services and it believes based on its good-faith medical judgment that delay would pose a risk to the patient’s “health.”

Similarly, laws that protect Catholic and other religious hospitals from providing abortion services would fail under H.R. 2975 if an individual doctor or nurse could show that such laws limit their ability to provide “immediate” abortion services and they believe based on their good-faith medical judgment that delay would pose a risk to the patient’s “health.”

H.R. 2975 fails to define the terms “health” and instructs courts to “liberally construe” provisions of H.R. 2975 to “effectuate” its purposes, thus opening the door to an expansive, permissive interpretation. Further, Section 4(a)(10) makes clear that the relevant standard is not the court’s judgment of what poses a health risk but rather the “good-faith medical judgment” of the abortionist. What’s more, Section 4(a)(10) fails to quantity the degree of “risk” any delay must “pose” to trigger effect under H.R. 2975 or whether such “risk” must meet at least a certain threshold of probability.

To wit, under Section 4(a)(10), almost any factor could be viewed as related to patient health, and a court could hold that any level of risk, however attenuated or slight, will do.

Note well, a law need not “single out” abortion to come within the strictures of Section 4(a)(10). Generally applicable laws such as religious freedom restoration acts, free exercise clauses in State constitutions, and even labor, employment, and civil rights laws otherwise coming within the scope of H.R. 2975 would all face jeopardy from Section 4(a)(10). Further, H.R. 2975 specifically states that it supersedes and applies to all Federal law notwithstanding any other provision of Federal law including the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. If H.R. 2975 strips pro-life doctors, nurses, and hospitals of protection, they would lack any further recourse from government except any claims they could establish under the U.S. Constitution.

Religious freedom and conscience protection laws that “single out” the abortion issue within the meaning of Section (4)(b)(2)(A) would face additional jeopardy under Section 4(b)(2) operating in conjunction with Section 4(c)(1)-(3) & (5).

If the sponsors of H.R. 2975 intend for H.R. 2975 not to disturb protections for health care providers conscientiously opposed to abortion, they could make that intention crystal clear—but they don’t.

Congress knows how to speak clearly and unambiguously when it wants to. H.R. 2975 itself, for example, cites to specific provisions of the U.S. Code in at least two instances and, in its list of exceptions, refers to “laws regulating physical access to clinic entrances.” In contrast, H.R. 2975 makes no reference to conscience protection laws except to clarify that the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act won’t save a law otherwise invalid under H.R. 2975.

Analysis of H.R. 2975 in its current form should be based on the very real possibility that it would strip prolife doctors and nurses and Catholic and other religious hospitals of vital civil rights and liberties protecting their freedom to conscientiously refuse to participate in abortion.

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize limits on taxpayer-funded abortion—including the Hyde Amendment

U.S. Supreme Court precedents establish that governments “need not commit any resources to facilitating abortions.”[20] However, H.R. 2975 would jeopardize the ability of both the State and Federal government to prohibit the use of taxpayer funds for the purpose of performing abortions.

The threshold question in analyzing the potential application of H.R. 2975 to any limit on taxpayer-funded abortion is whether such limit comes within the scope of H.R. 2975 generally. Section 4(e)(2) includes a list of “exceptions” including Section 4(e)(2)(B), which states that the provisions of H.R. 2975 do not supersede or apply to “insurance or medical assistance coverage of abortion services.” Therefore, State and Federal limits on taxpayer-funded abortion that come within the meaning of “insurance or medical assistance coverage of abortion services” would survive the application of H.R. 2975, whereas limits outside that exception would be subject to jeopardy under H.R. 2975.

H.R. 2975 does not define the phrase “insurance or medical assistance coverage of abortion services.”

If the sponsors of H.R 2975 intend for H.R. 2975 not to apply to limits on taxpayer funded abortion such as the Hyde Amendment, the Mexico City Policy, limits on abortion in Title X family planning programs, and similar policies set out elsewhere in Federal law and in the laws of the States, they could easily make that intention crystal clear—but they don’t.

Accordingly, analysis of H.R. 2975 in its current form should be based on the possibility that any limit on taxpayer-funded abortion—including the Hyde Amendment, the Mexico City Policy, and restrictions attached to Title X family planning funds—that does not clearly and unambiguously come within the meaning of “insurance or medical assistance coverage of abortion services” will be adjudged to fall within the scope of H.R. 2975.

Even if good arguments exist for why any particular limit on taxpayer-funded abortion comes within the meaning of “insurance or medical assistance coverage of abortion services,” there is no certainty that courts will see the argument in the same way unless Congress clearly and unambiguously dictates that conclusion. Federal courts sometimes interpret statutory terms in unpredictable and counterintuitive ways. See, e.g., National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 132 S. Ct. 2566, 2596 (2012) (concluding that “what is called a ‘penalty’ here may be viewed as a tax”). What’s more, courts may reason that Congress knows how to draft abortion rights legislation that unambiguously protects limits on taxpayer-funded abortion and chose not to do so here. In 1993, U.S. Senate Bill 25, the Freedom of Choice Act of 1993, was reported to the Senate with language stating that “[n]othing in this Act shall be construed to . . . prevent a State from declining to pay for the performance of abortions.”[21] Courts might conclude that the omission of similarly unambiguous language in H.R. 2975 supports the understanding that H.R. 2975 does not intend and was not intended to exclude limits on taxpayer-funded abortions from application of H.R. 2975.

If any given limit on taxpayer-funded abortion falls within the scope of H.R. 2975, it would face jeopardy under multiple provisions including Section 4(a)(8), Section 4(a)(9), and Section 4(a)(10) as well as Section 4(b)(2) operating in conjunction with any of Section 4(c)(1), Section 4(c)(2), Section 4(c)(3), and Section 4(c)(5).

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize parental notice requirements

As reported by the pro-abortion Guttmacher Institute, “The majority of states require parental involvement in a minor’s decision to have an abortion.”[22]

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize parental involvement requirements. This result would deprive adolescents of the counsel of family members with the most knowledge of the adolescent’s health and well-being, as well as benefit sex traffickers who seek to procure abortions for minors without the risk of discovery posed by laws requiring parental involvement in the abortion decision.

Section 4(b)(2) creates a statutory right to provide or obtain an abortion without any limitation or requirement that “singles out the provision of abortion services” and “impedes access” to abortion services based on one or more of the factors described in Section 4(c). The Section 4(c) factors include whether the limitation or requirement “is reasonably likely to delay some patients in accessing abortion services” and whether the limitation or requirement “interferes” with an abortionist’s ability to “provide care and render services” in accordance with the abortionist’s “good-faith medical judgment.”

Abortionists would easily satisfy the elements of a claim under Section 4(b). Laws requiring parental involvement specifically in the context of a teenager’s abortion decision obviously “single[] out” abortion. It is almost certain that parental involvement laws will “delay” at least “some” teenagers in “accessing abortion services.” Further, it’s no stretch to imagine abortionists such as Kermit Gosnell, James Pendergraft, and George Klopfer arguing that parental involvement requirements “interfere[]” with their ability to “provide care and render services” in accordance with their “good-faith medical judgment.”

Once abortionists have established a claim under Sections 4(b), the key question would be whether a State could satisfy the Section 4(d) defense, which would require the State to establish, “by clear and convincing evidence,” that the parental involvement requirement “significantly advances” by the least restrictive means either “the safety of abortion services” or the “health of patients.”

The Section 4(d) defense excludes core interests advanced by parental involvement requirements such as protecting vulnerable teenagers, helping teenagers think through the long-term consequences of taking the life of their own child, providing the kind of loving and individualized counsel a disinterested abortionist cannot be expected to provide, and the rights and obligations of parents to take personal accountability for the formation of their families and rearing of their own children.

These interests are reasonable and praiseworthy and it is fitting and right for government to recognize, support, and advance them. However, insofar as parental involvement requirements advance these interests but not one of the two narrow interests encompassed by the crabbed confines of Section 4(d), those parental notice requirements would fail under H.R. 2975.

Even if a State could show that parental involvement laws had the effect of increasing the “safety of abortion services” or the “health of patients,” the State would still need to show that the requirement “significantly” advances these narrow interests and could not be achieved by a “less restrictive” measure such as substituting, as to health and safety questions, the “medical judgment” of licensed medical professionals for the “parental judgment” of a teenager’s parents.

And even if the State could make that showing, it would still need to establish this defense by “clear and convincing evidence,” a legal standard described by the pro-abortion Guttmacher Institute as “unusually strict.”[23]

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize parental involvement laws. If the sponsors of H.R. 2975 do not intend for it to jeopardize parental involvement laws, then they should amend the legislation to make that intention crystal clear.

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize informed consent laws such as ultrasound requirements and reflection periods

Several States require abortion providers, before providing an abortion, to conduct an ultrasound and to share or offer to share the image with the mother.[24]

In addition, some States have required abortion providers, before providing an abortion, to test or offer to test for fetal heartbeat and to offer the mother the opportunity to view or listen to the heartbeat of her unborn child.[25]

Further, more than half the States mandate a reflection period, most often 24 hours, before a woman may subject herself and her unborn child to an abortion.[26]

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize each of these pro-baby, pro-woman polices thereby putting women’s health at risk.

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize ultrasound and fetal heartbeat tests.

Section 4(a)(1) creates a statutory right to perform or obtain an abortion without any “requirement that a health care provider perform specific tests or medical procedures in connection with the provision of abortion services, unless generally required for the provision of medically comparable procedures.”

The term “medically comparable procedures” means “medical procedures that are similar in terms of health and safety risks to the patient, complexity, or the clinical setting that is indicated.”

The concept of “medically comparable procedures” encompasses surgical as well as medication abortions.

In defining the term “medically comparable procedures,” H.R. 2975 puts abortion in the context of “hysteroscopies, “sigmoidoscopy,” and “loop electrosurgical excision procedures.”

It would be irrational for States to require ultrasound or fetal heartbeat tests in most if not all contexts outside abortion even if those contexts involved procedures adjudged by courts as “medically comparable” to abortion within the meaning of H.R. 2975.

Abortion is a unique procedure that involves a woman choosing to intentionally end the life of the unborn child that lives within her. Informed consent in this context involves comprehending the full humanity of the child and freely choosing to end the child’s life anyhow.

Ultrasound and fetal heartbeat test requirements advance informed consent in the abortion context. In other contexts, such requirements, applied generally, would be irrational, not based on evidence, and might even be contraindicated by the medical needs of the woman.

Indeed, in cases where a woman was not pregnant it would be categorically impossible to satisfy a fetal heartbeat test requirement.

Confronted with these realities, it’s unlikely, as a practical matter, that many if any States would seek to defend or enact laws imposing ultrasound and fetal heartbeat test requirements before conducting abortion.

Ultrasound and fetal heartbeat requirements would also face jeopardy from Section 4(b)(2) operating in conjunction with Section 4(c)(1)-(4) if States defending those laws were unable, as set out in Section 4(d), to establish “by clear and convincing evidence” the reflection period “significantly advances” in the least restrictive way the safety of abortion services or the health of patients. Although States can make arguments as to each of the Section 4(d) elements, there is no guarantee courts would rule in their favor and the risk from pro-abortion, activist judges is real.

H.R. 2975 poses a similar threat to mandatory reflection periods.

Section 4(a)(7) creates a statutory right to perform or obtain an abortion without any “requirement that, prior to obtaining an abortion, a patient make one or more medically unnecessary in-person visits to the provider of abortion services or to any individual or entity that does not provide abortion services.” If courts judged reflection periods as “medically unnecessary” then such requirements would fail under Section 4(a)(7) insofar as they require a separate visit.[27]

As with ultrasound and heartbeat tests, mandatory reflection periods would also face jeopardy from Section 4(b)(2) operating in conjunction with Section 4(c)(1)-(4).

H.R. 2975 would block States from protecting pain-capable babies at 20 weeks of pregnancy in most cases

Section 4(a)(8) creates a statutory right to perform or receive an abortion without any limit from “[a] prohibition on abortion prior to fetal viability.” Fetal viability occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy in most cases.[28] Therefore Section 4(a)(8) would block 20-week laws in most cases.

Any application of 20-week laws surviving Section 4(a)(8) on grounds that a baby was viable would face significant jeopardy under Section 4(a)(9) as well as Section 4(b)(2) operating in conjunction with Section 4(c)(1).

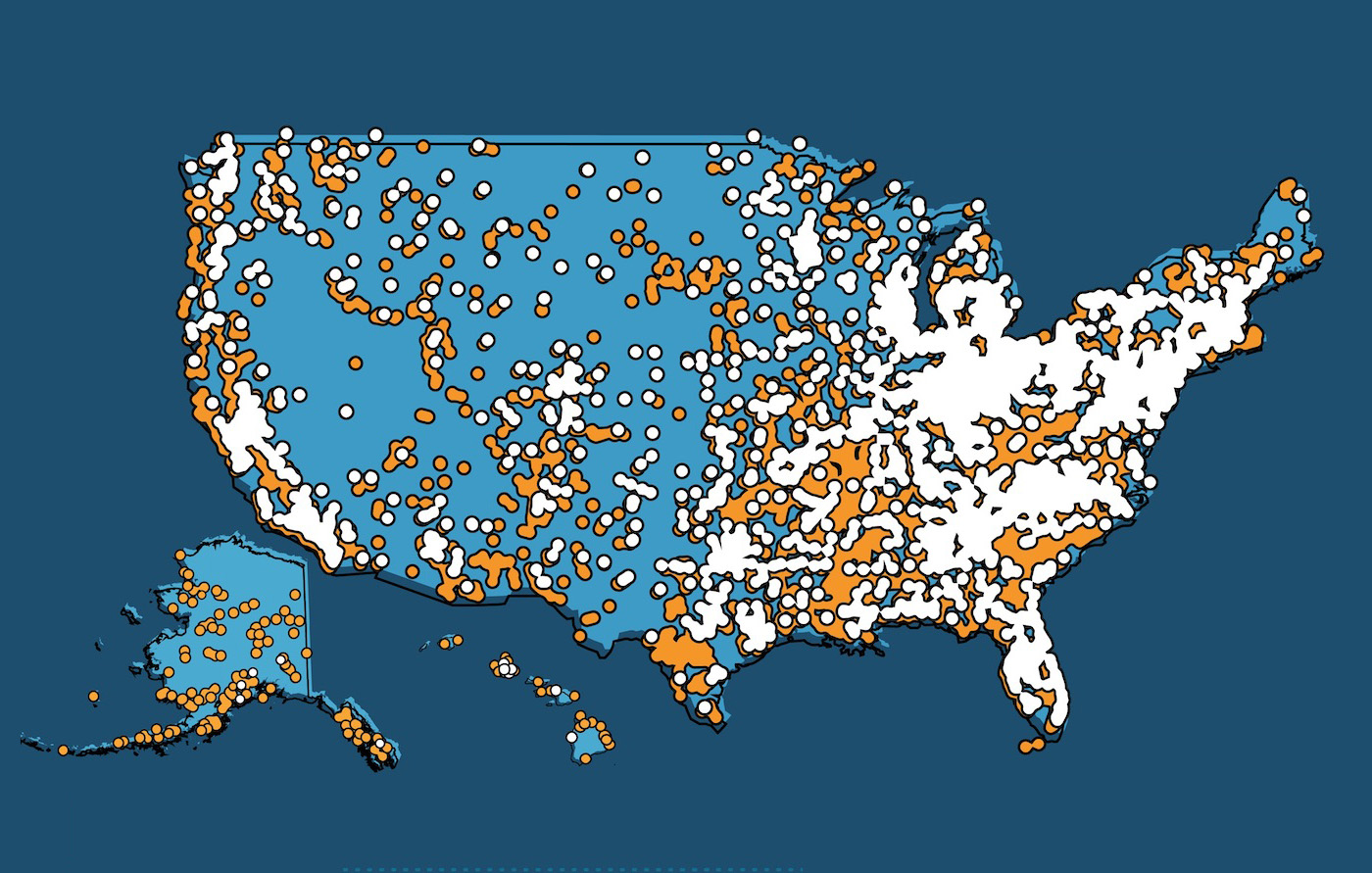

Since 2010, twenty-one States have enacted laws limiting abortion at 20 weeks (almost five months) of pregnancy.[29] Despite this wave of pro-life legislation, outside the Ninth Circuit, abortion proponents have challenged only two of those 21 laws, including a state law case in Georgia that failed.[30] This lack of litigation shows a real concern on the part of abortion activists that they will lose in court when it comes to limits on late abortion.

With a single blow, H.R. 2975 would accomplish a crushing pro-abortion victory that abortion activists have been largely unwilling to attempt in the courts.

H.R. 2975 would force States to allow discrimination

In 2019 Justice Clarence Thomas clarified that whether government may restrict the eugenic practice of discrimination abortion based on the race, sex, or disability of the child presents an “issue of first impression” and “remains an open question.”[31]

H.R. 2975 would “close” that question by forcing States to allow the eugenic practice of discrimination abortion before the point of viability.

Section 4(a)(11) creates a statutory right to perform or receive an abortion without either

- “[a] requirement that a patient seeking abortion services prior to fetal viability state the patient’s reasons for seeking abortion services” or

- “a limitation on the provision of abortion services prior to fetal viability based on the patient’s reasons or perceived reasons for obtaining abortion services.”

This language would invalidate the previability application of State laws that prohibit the eugenic practices of Down syndrome discrimination abortion, sex-selection abortion, and race-based abortion.

H.R. 2975 would make it harder to limit late abortions

After viability a State may proscribe abortion “except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”[32] This rule is often referred to as the “health exception.”

The scope of the health exception required by the U.S. Supreme Court has been subject to debate. If the term “health” is construed broadly, for example, to include any psychological, social, or emotional impact whatsoever, the exception has the effect of making abortion available throughout all of pregnancy without meaningful restriction.

“Some States have crafted health exceptions that include physical but not psychological health and other States might not specify whether health exceptions to post-viability abortion restrictions include mental health. Further, some States [have] require[d] that a second physician certify that the abortion is medically necessary in all or some circumstances.”[33]

H.R. 2975 would jeopardize the ability of States to establish meaningful health exceptions to restrictions on late abortion that might otherwise be allowed by courts.

Section 4(a)(9) creates a statutory right to perform or obtain an abortion without any limitation from “[a] prohibition on abortion after fetal viability when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating health care provider, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant patient’s life or health.”

H.R. 2975 fails to define the terms “health” and instructs courts to “liberally construe” provisions of H.R. 2975 to “effectuate” its purposes, thus opening the door to an expansive, permissive interpretation. Further, Section 4(a)(9) makes clear that the relevant standard is not the court’s judgment of what poses a health risk but rather the “good-faith medical judgment” of the “treating” abortionist. What’s more, Section 4(a)(9) fails to quantity the degree of “risk” that continuation of the pregnancy must “pose” to trigger effect under H.R. 2975 or whether such “risk” must meet a certain threshold of probability.

To wit, under Section 4(a)(9), almost any factor could be viewed as related to patient health, and a court could hold that any level of risk, however attenuated or slight, will do. In practice, the Section 4(a)(9) “health” exception would make it very difficult for States to enforce post-viability limits on abortion that might otherwise be allowed by courts.

Thomas M. Messner, J.D. serves as Senior Fellow in Legal Policy at the Charlotte Lozier

[1] Press Release: “Stockman urges House to defeat Abortion On Demand Act,” Jul. 8, 2014 (commenting on the Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013, H.R. 3471, 113th Cong. (2013)), https://web.archive.org/web/20140711062434/http://stockman.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/stockman-urges-house-to-defeat-abortion-on-demand-act.

[2] Guttmacher Inst., Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortions (Feb. 1, 2020), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/parental-involvement-minors-abortions.

[3] Greenville Women’s Clinic v. Bryant, 222 F.3d 157, 173 (4th Cir. 2000).

[4] Planned Parenthood of Se. Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 852 (1992) (opinion of the Court).

[5] Planned Parenthood of Central Missouri v. Danforth, 428 U.S. 52, 91 (1976) (Stewart, J., concurring).

[6] Bellotti v. Baird, 443 U.S. 622, 649 (1979) (plurality opinion).

[7] Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297, 325 (1980).

[8] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 159 (2007).

[9] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 159 (2007).

[10] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 160 (2007).

[11] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 163 (2007) (discussing Casey).

[12] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 146 (2007).

[13] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 157 (2007) (quoting Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 731 (1997)).

[14] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 158 (2007).

[15] Planned Parenthood of Se. Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 882 (1992) (plurality opinion)

[16] Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124, 159 (2007).

[17] In re T.W., 551 So. 2d 1186, 1194 (1989) (Fla.) (describing the state’s interests “taken into consideration” by the Supreme Court “[i]n evaluating the validity of parental consent and notice statutes”).

[18] Mark L. Rienzi, The Constitutional Right Not to Kill, 62 EMORY L.J. 121, 148–49 (2012).

[19] See U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Servs., Conscience Protections for Health Care Providers (Mar. 22, 2018), https://www.hhs.gov/conscience/conscience-protections/index.html.

[20] Webster v. Reprod. Health Servs, 492 U.S. 490, 511 (1989).

[21] The Freedom of Choice Act of 1993, S. 25, 103d Cong. § 3(b)(2) (as reported to the Senate on Apr. 29, 1993).

[22] Guttmacher Inst., Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortions (Feb. 1, 2020), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/parental-involvement-minors-abortions.

[23] Guttmacher Inst., Parental Involvement in Minors’ Abortions (Feb. 1, 2020), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/parental-involvement-minors-abortions.

[24] Guttmacher Inst., Requirements for Ultrasound (Feb. 1, 2020), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/requirements-ultrasound.

[25] See Thomas M. Messner, The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013: The Sweeping Impact of S. 1696, Charlotte Lozier Inst., July 1, 2014, https://lozierinstitute.org/the-womens-health-protection-act-of-2013-the-sweeping-impact-of-s-1696/.

[26] See Guttmacher Inst., Counseling and Waiting Periods for Abortion (Feb 1, 2020) (reporting that “34 states require that women receive counseling before an abortion is performed” and “27 of these states also require women to wait a specified amount of time—most often 24 hours—between the counseling and the abortion procedure”), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/counseling-and-waiting-periods-abortion.

[27] See Guttmacher Inst., Counseling and Waiting Periods for Abortion (Feb 1, 2020) (reporting that “14 states require that counseling be provided in person and that the counseling take place before the waiting period begins, thereby necessitating two separate trips to the facility”), https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/counseling-and-waiting-periods-abortion.

[28] Jeffrey Kluger, “Viable at 22 Weeks: Just How Low Can Preemies Go?,” time.com, May 7, 2015, https://time.com/3850255/premature-babies-22-weeks/.

[29] Thomas M. Messner and Amanda Stirone Mansfield, Legislative and Litigation Overview of Five-Month Abortion Laws Enacted Before or After 2010, Charlotte Lozier Inst. (Aug. 13, 2019), https://lozierinstitute.org/legislative-and-litigation-overview-of-five-month-abortion-laws-enacted-before-or-after-2010/.

[30] Thomas M. Messner and Amanda Stirone Mansfield, Legislative and Litigation Overview of Five-Month Abortion Laws Enacted Before or After 2010, Charlotte Lozier Inst. (Aug. 13, 2019), https://lozierinstitute.org/legislative-and-litigation-overview-of-five-month-abortion-laws-enacted-before-or-after-2010/.

[31] Kristina Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, No. 18-483 (2019) (slip op. at 4, 20) (Thomas, J., concurring), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/18pdf/18-483_3d9g.pdf.

[32] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 164 (1973).

[33] Thomas M. Messner, The Women’s Health Protection Act of 2013: The Sweeping Impact of S. 1696, Charlotte Lozier Inst., July 1, 2014 (internal quotations omitted), https://lozierinstitute.org/the-womens-health-protection-act-of-2013-the-sweeping-impact-of-s-1696/.