Time to End Embryo-Destroying Stem Cell Research

Will induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) finally replace human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) in the field of regenerative medical research?

Results of a recent study published in Nature Biotechnology argue that they should.

First, some background.

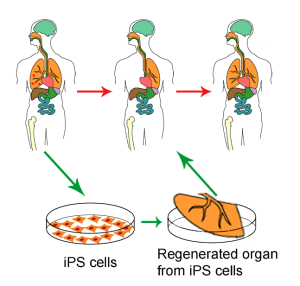

In 2007, Japanese scientist Shinya Yamanaka discovered a method to create fully pluripotent, embryonic-like stem cells from ordinary somatic (body) cells. The ability to do this had been characterized as the “holy grail” of stem cell research and, indeed, Yamanaka’s achievement changed the field of regenerative medicine. So groundbreaking was his discovery that he was awarded the Nobel Prize just five years after announcing it.

Yamanaka dubbed these cells “induced pluripotent stem cells” (iPSCs) because they are generated by inducing somatic cells (such as an ordinary skin cell) into a pluripotent state, making them the functional equivalent of pluripotent embryonic stem cells. In other words, researchers could now obtain abundant pluripotent stem cells without having to destroy embryos.

Indeed, Yamanaka himself has said that what motivated his discovery was his determination to find a way to end the destruction of human embryos for their stem cells. Remembering looking at a human embryo through a microscope several years before his breakthrough, Yamanaka said, “When I saw the embryo, I suddenly realized there was such a small difference between it and my daughters… I thought, we can’t keep destroying embryos for our research. There must be another way.”

Many researchers hailed the advent of iPSCs as largely resolving that ethical dilemma associated with embryonic stem cell research, as human embryos would no longer have to be destroyed for their stem cells. Among the scientists celebrating the discovery was James Thomson, the scientist credited with first isolating hESCs, in 1998. “It is the beginning of the end of the controversy that has surrounded this field,” Thomson said at the time.

Still, Thomson added that hESCR should continue in order to see that the iPSCs “do not differ from embryonic stem cells in a clinically significant or unexpected way,” and most other researchers agreed.

Which brings us back to the recent study published in Nature Biotechnology. The study addresses exactly that question: do iPSCs differ in any significant way from hESCs?

After submitting both hESC lines and iPSC lines to several tests, the authors concluded: no, they do not. “We conclude that hESCs and hiPSCs are molecularly and functionally equivalent and cannot be distinguished by a consistent gene expression signature,” they wrote.

“The ultimate test of a stem cell is its ability to produce different cell types. ES cells and iPS cells were equally good at specializing into a variety of nervous system cells,” the journal Science wrote, reporting on the study. “They also ran a standard test that measures the cells’ ability to produce the three major cell lineages in the body and found no differences.” The article then quotes Konrad Hochedlinger, a member of the research team: “The two cell types appear functionally indistinguishable based on the assays we used.”

As previously noted on this website, when President Clinton’s National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC) first endorsed federal funding for hESCR, it did so conditionally. Harvesting so-called “left-over” IVF embryos for stem cells “is justifiable only if no less morally problematic alternatives are available for advancing the research” (at pg. 53). At the time – 1999 – the NBAC did not believe that such alternatives existed. However, it added, “this is a matter that must be revisited continually as science advances.”

Today, 16 years later, science has advanced to the point where researchers can declare iPSCs “functionally indistinguishable” from hESCs, meaning researchers now have a virtually limitless supply of pluripotent stem cells that is relatively easy to obtain and most important does not rely on the destruction of human embryos.

If the members of the NBAC panel were serious and are to be taken seriously, then it’s time to end the destruction of human embryos for research purposes.

Gene Tarne is a senior analyst with the Charlotte Lozier Institute.