Canada May Make Mentally Ill Subject to Assisted Suicide

Just two years ago, Canada’s Supreme Court decriminalized physician-assisted suicide (PAS) and euthanasia in its decision in Carter v. Canada. In that February 6, 2015, ruling, the Court allotted a one-year window to Parliament within which to pass legislation regulating the practices. The result was Bill C-14, passed on June 17, 2016, which permits adults with a “serious and incurable illness, disease or disability” who are enduring “physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them” to request PAS or euthanasia if their natural death is “reasonably foreseeable.”

Now Canada is considering explicitly creating eligibility for PAS and euthanasia to those suffering from mental illnesses. In December, the government tasked the Council of Canadian Academies with conducting a review of several issues related to the law—whether regulations should be relaxed so as to allow for advance requests for PAS and euthanasia, whether minors should be eligible, and whether those suffering from mental illnesses should be eligible. The Council is expected to report back to Parliament by the end of 2018 with its recommendations.

Even before C-14 was originally passed, the Parliament considered looser requirements for eligibility. The Senate amended the bill to delete the stipulation that a person’s natural death must be “reasonably foreseeable,” but the House rejected that amendment during the bill’s final passage. The stipulation—that a person’s natural death must be reasonably foreseeable to be eligible for PAS and euthanasia—is unclear on its own, but the proceedings leading to C-14’s passage establish that Parliament already had in mind an extension of eligibility beyond those whose deaths are “reasonably foreseeable,” whatever that language might mean.

The extension of eligibility for PAS and euthanasia to the mentally ill carries the air of inevitability about it—because it was already countenanced by half of the Canadian parliament during the bill’s original passage, yes, but also because of the logical implications of a society committing itself to the premise that an acceptable response to human suffering for anyone is PAS or euthanasia.

One can easily experience a sense of déjà vu while following the evolution of PAS and euthanasia in countries that have decriminalized the practices. Richard Doerflinger captured the familiar track in an interview with Charlotte Lozier Institute earlier this year: “In the Netherlands, Belgium, and other countries with longer experience of this agenda, the killing has moved steadily from assisted suicide to euthanasia; from terminally ill patients to those with chronic illness, mental illness, or simple weariness of life; and from voluntary to nonvoluntary euthanasia.”

These developments give the impression of a steady, unstoppable march towards full access to—and perhaps even forced—PAS and euthanasia, but the history has not been written yet. This evolution is not inevitable.

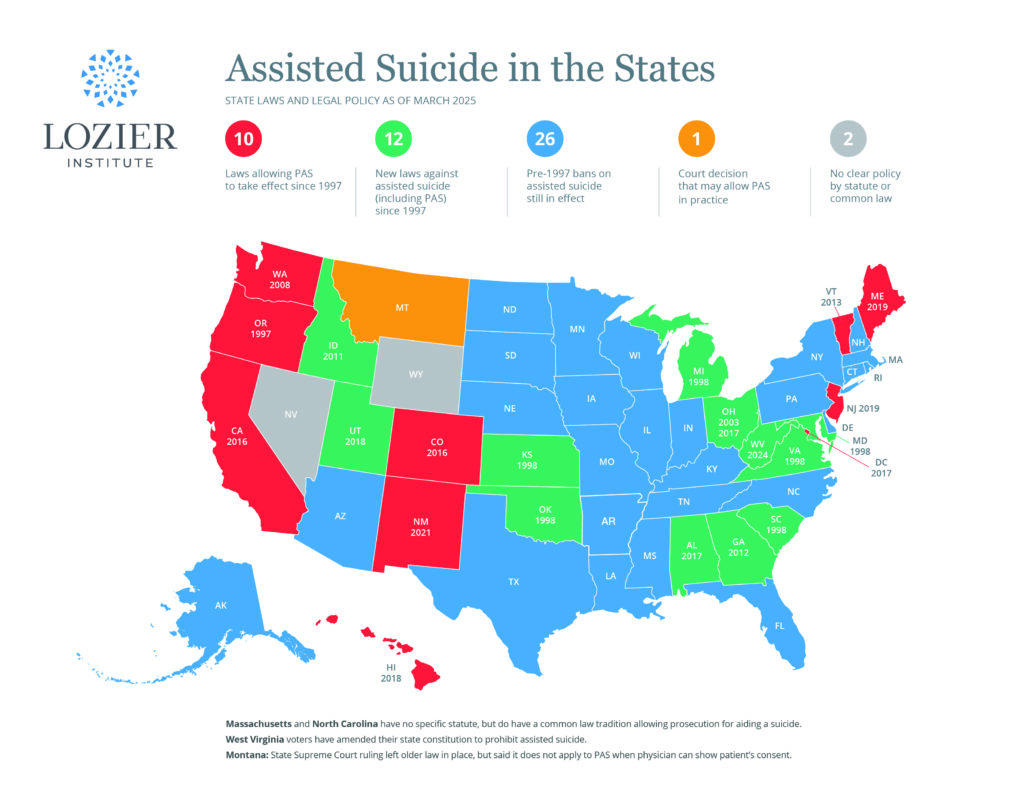

Both in Canada and other countries that have decriminalized the practices, and in the U.S. where states are beginning to normalize them piecemeal, the arguments of proponents of PAS and euthanasia should be met head-on. Some will paint the expansion of the law in Canada as an extension of freedom and choice to a larger group of people. In truth, it represents the government signaling to another group of people that their lives are not worth living. Doerflinger argues that

allowing assisted suicide for one vulnerable class of people actually subjects them to the will of others – from greedy or uncaring relatives, to ethically challenged doctors, to society itself. When we exempt a whole class of people from the usual laws protecting life, that’s not about freedom – it’s about the government’s decision that some people are worth protecting, but other people are not, when they are tempted to make self-destructive choices.

In addition to the harms that will be done to those suffering from mental illnesses should Canada expand its law, the integrity of the medical profession in that country will be further vitiated. Already in one Canadian province, all physicians are mandated to provide “effective referrals” for patients seeking PAS or euthanasia. Ontario is unique in this transparent disregard for the religious integrity and conscience rights of its physicians for now, but it may not be so for long.

Wesley Smith notes in First Things that medical elites are abandoning respect for conscience and adopting a more coercive outlook. “Bioethicists and other medical elites have launched a frontal assault against doctors seeking to practice their professions under the values established by the Hippocratic Oath,” Smith writes. “In the last year, these efforts have moved from the relative hinterlands of professional discussions into the center of establishment medical discourse.”

Smith details a recent attack on conscience written by prominent bioethicists Ezekiel Emanuel and Ronit Y. Stahl in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. In their piece, they argue that health care professionals must provide, at the least, timely referrals to ensure patients receive access to procedures the professional objects to on conscience grounds, if the requested service is “professionally accepted” as an appropriate medical intervention. Emanuel and Stahl consider the provision of contraceptives and abortions to fall within this sphere, but exclude PAS and euthanasia because they are not generally accepted within the medically community. But, Smith notes, that could change rather quickly.

The upshot of this increase in contempt for conscientious objection in the professional medical arena is that it threatens to run pro-life health care professionals out of the metaphorical town. Smith observes

When doctors refuse to abort a fetus, participate in assisted suicide, excise healthy organs, or otherwise follow their conscience about morally contentious matters, they send a powerful message: Just because a medical act is legal doesn’t make it right. Such a clarion witness is intolerable to those who want to weaponize medicine to impose secular individualistic and utilitarian values on all of society.

The environment for physicians in Ontario is indicative of what can happen when respect for the conscience rights of health care professionals is discarded. More patients (and conscientious health care professionals) may soon be at risk if Canada extends PAS and euthanasia to the mentally ill. Those in the U.S. who do not wish to see those practices normalized in their own society would do well to take realistic stock of what is happening—and how quickly it has happened—in Canada, to renew their efforts to prevent the further spread of these practices across the country, and ultimately to reverse them and restore the ethical mandate to “do no harm.”

Tim Bradley is a research associate at the Charlotte Lozier Institute.