Give Me Liberty and Give Me Death?

Death by euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide is primed to take off in Canada, as Parliament passed Bill C-14 on June 17. The law, which establishes guidelines under which Canadians can receive assistance in killing themselves or be euthanized by medical personnel, received royal assent the same day. Royal assent can be supplied by the Governor General and does not denote approval by Buckingham Palace.

C-14 represents the culmination of a process that was set in motion more than a year and a half ago. The Supreme Court of Canada decriminalized assisted suicide and euthanasia in its decision in Carter v. Canada on February 6, 2015.

In that decision the unanimous court held “that the prohibition on physician-assisted dying is void insofar as it deprives a competent adult of such assistance where (1) the person affected clearly consents to the termination of life; and (2) the person has a grievous and irremediable medical condition … that causes enduring suffering that is intolerable to the individual in the circumstances of his or her condition.” Included in the court’s consideration of qualifying medical conditions is “physical or psychological” pain.

The ruling, therefore, does not confine the “right” to die at the hands of a doctor or with a doctor’s assistance to those with terminal illnesses. Wesley J. Smith notes in the Weekly Standard that “a treatable condition can qualify as ‘irremediable’ if the patient chooses not to pursue available remedies. So an ‘irremediable’ condition that permits life-termination may actually be wholly remediable, except that the patient would rather die than receive care.”

The court’s ambiguous wording and lax standards in its opinion thus set a dangerous precedent for determining who possesses a legal right to assisted suicide or euthanasia. Not only did the court’s opinion instigate confusion, but it also overruled the stable and demonstrated will of the Canadian parliament—the House of Commons had debated six separate bills seeking to legalize assisted suicide between 1991 and 2010, and zero passed.

The court granted Parliament a one-year window (which was then extended) following the Carter decision within which to enact laws to regulate the now-legalized practices of assisted suicide and euthanasia. The result: C-14.

The bill was not passed without acrimony. The final version approved as law maintains that a person’s death must be “reasonably foreseeable” in order to qualify for assisted suicide or euthanasia. The Senate, however, removed that clause in an amendment to the bill, seeking to broaden access to the newly dictated “right” to die. The House of Commons rejected the Senate’s amendment during the bill’s final passage.

The law’s overall effect is to “create exemptions from the offences of culpable homicide, of aiding suicide and of administering a noxious thing, in order to permit medical practitioners and nurse practitioners to provide medical assistance in dying and to permit pharmacists and other persons to assist in the process.”

To be eligible for assisted suicide or euthanasia, an adult must have a grievous and irremediable medical condition. This entails that the person: “have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability”; be in a state of “irreversible decline in capability”; be enduring “physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them”; and have a reasonable foresight as to their natural death occurring, “without a prognosis necessarily having been made as to the specific length of time that they have remaining.”

Aside from the fact that Parliament was compelled to pass some law providing regulations for the practices of assisted suicide and euthanasia by Supreme Court dictate—and contrary to established Parliamentary practice and precedent—C-14 raises at least two serious problems.

First, the law does not provide adequate protection for the weak and the vulnerable. The criteria a person must meet to be eligible for assisted suicide are extremely vague. Various illnesses and disabilities may be serious and incurable, but at the same time may not be terminal and may, in fact, be ameliorated by proper treatment and care. Intolerable physical or psychological suffering could result from any number of causes, not only from terminal illnesses, or incurable ones. Psychological suffering as a criterion opens the door to far too many potential cases, including those where a patient’s outlook is traceable to neglect by others.

The logic of legalized assisted suicide and euthanasia is that there are some lives that simply are not worth living. Legalizing such practices will reduce “efforts to explore and maintain effective pain management in palliative care and long-term care,” according to Carter Snead, professor of law at the University of Notre Dame. In the case of Canada, the new law leaves those most vulnerable to pressures to end their lives prematurely—and those who might most benefit from more, not less, effort to help them with treatable conditions such as depression—without protection.

Second, Canadian doctors and nurses will face new challenges to their religious liberty and conscience rights. Smith notes at First Things that already civil liberties groups and government commissions are pressuring for laws that would force doctors and nurses with conscience-based objections to assisted suicide and euthanasia to cooperate in these practices.

One federal panel recommended that the government work towards a compromise that respects a health care practitioner’s freedom of conscience and the needs of patients by requiring objecting practitioners to, at a minimum, “provide an effective referral for a patient.” The problem with a compromise such as this is that it fails to protect objecting practitioners—providing a referral for assisted suicide or euthanasia constitutes cooperation with the very practice to which the practitioners object.

Or consider a hospital in Quebec that is being pressured by that province’s health minister to provide euthanasia in the hospital’s palliative care department. Note that the hospital does not forbid assisted suicide and euthanasia—it merely requires that patients be moved out of the palliative care department before their lives are ended. Cases such as this promise to become more and more frequent as assisted suicide and euthanasia become more common.

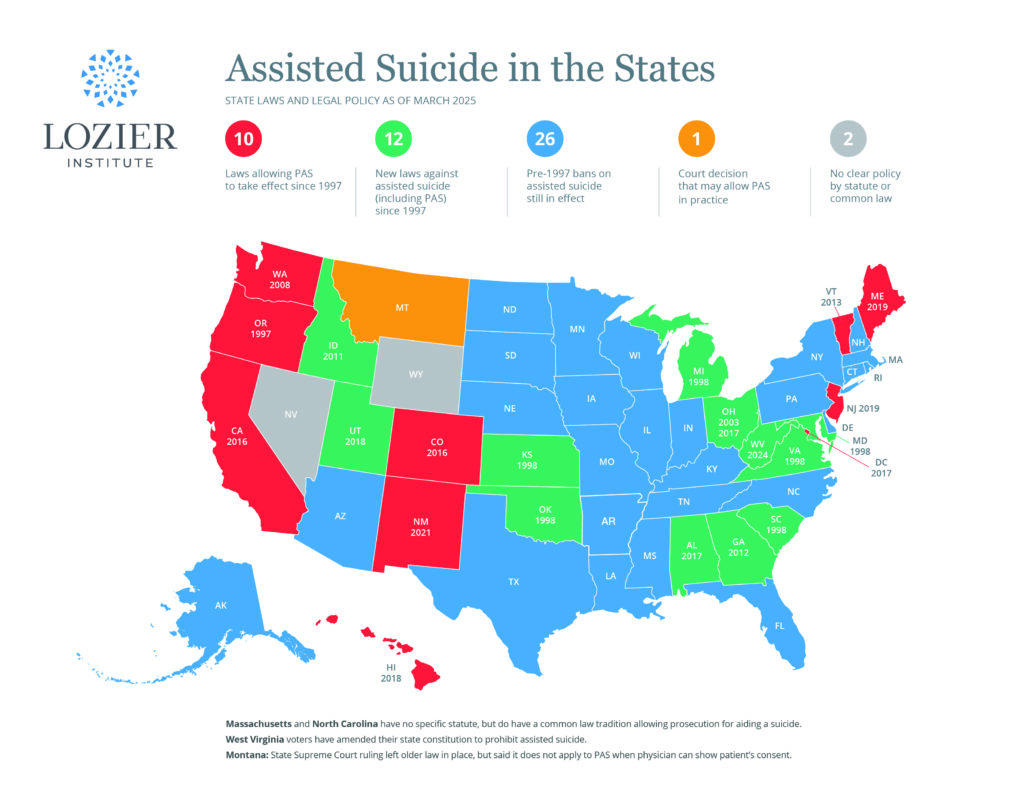

Canada’s legalization of these deadly practices—first at the command of the Supreme Court and now regulated by law passed by Parliament—signals another victory for the culture of death. Those watching trends in the legalization of assisted suicide in parts of the United States would be wise to monitor developments by our neighbor to the north.

Tim Bradley is a research associate at the Charlotte Lozier Institute.