UK Government Panel Approves Genetically Engineered “Three-Parent” Embryos

Great Britain’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which oversees fertility treatments and embryo research in that nation, recently approved fertility procedures that would amount to the genetic engineering of children through cloning (nuclear transfer) technology and germ-line modification, resulting in a “three-parent embryo” that would have genetic material from two mothers and one father.

Proponents of such an unprecedented step provide a therapeutic rationale to justify taking it: the fertility procedures envisioned are aimed at creating embryos free from mitochondrial defects which can give rise to serious diseases and defects after birth.

The majority of a cell’s genetic material is contained within its nucleus. The mitochondria are organelles that lie outside the nucleus and serve to provide energy for the cell; they also contain some genetic material (mtDNA). Only a mother’s mitochondria are passed on to offspring, so if the mother’s mitochondria have defects, this can eventually result in diseases to the child who has inherited from her the flawed mitochondria.

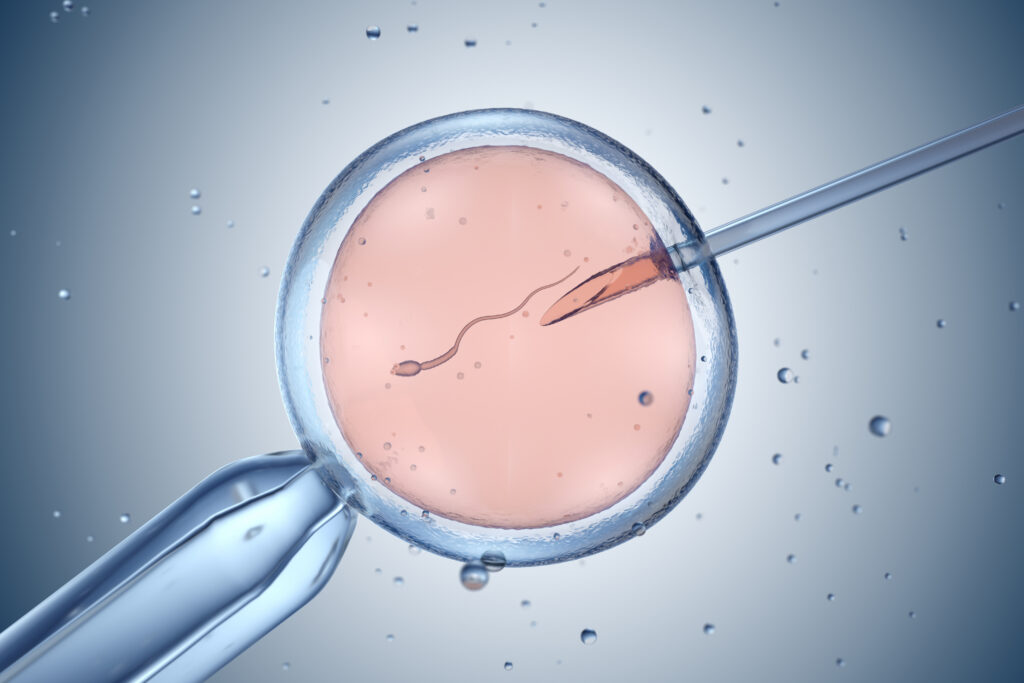

Researchers in Great Britain have developed a method that attempts to remedy this and create an embryo free of mitochondrial defects it would otherwise contain. To achieve this, researchers use a cloning technique called pro-nuclear transfer (PNT): the father’s sperm is used to fertilize the mother’s egg which contains the defective mitochondria, creating one embryo. However, a second egg from a donor, containing healthy mitochondria, is also fertilized, producing a second embryo. The nuclei from both embryos are removed, thus destroying them both. The nucleus from the embryo with the defective mtDNA is placed in the de-nucleated embryo “shell” with the healthy mtDNA. The resulting third embryo, which is then implanted in the mother, thus has genetic materials from two mothers and one father, thus the phrase “three-parent embryo”.

The procedure itself is currently illegal in Britain, as British law prohibits implantation of embryos that have been genetically modified, as this procedure does. The HFEA now favors changing the law to allow this procedure to eventually become a routine part of fertility treatments there.

While the goal of trying to prevent mitochondrial-caused diseases is of course a worthwhile one, the ethical alarms set off by this way of doing so are numerous.

Most obviously, the procedure destroys two embryos in order to produce a genetically modified third one. And because this is a new technology, there is no way of knowing what the impact will be on the child created through this experimental three-parent technique. The child would be born with the DNA from the father, the mother and the woman who donates (or sells) her egg. This is human experimentation on progeny who are incapable of giving consent.

Moreover, the modifications made are germ-line, meaning they would be passed on to future generations; this has never been done before. While proponents of this procedure justify this germ-line modification because it eliminates undesirable traits that may lead to disease (the mtDNA), doing so for the first time virtually invites eugenically motivated future germ-line modifications to insert desirable ones. This would turn children into genetically engineered and enhanced commodities.

Finally, there is the problem of the risks to otherwise healthy young women who are being asked to donate their eggs. Should the “three-parent” procedure prove effective and become routine, the amount of eggs this procedure would require would be considerable, in addition to the large number of eggs that would be needed to carry out the research needed to get to that point.

The risks entailed by getting eggs outside of a woman’s body (e.g., click here) are present in the short and long term, as women must undergo injections of powerful hormones to cause the ovaries to produce many eggs in one cycle. Among the many known risks to this procedure, the most severe is ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome (OHSS), which in rare cases causes death. The medical literature indicates that young women are more at risk for developing OHSS, just the target audience for this practice. In addition, there are the risks associated with anesthesia and the surgery necessary to remove the eggs. Longer-term risks, such as the risk of harm to the donors’ own fertility or the risk of later developing cancer, are more unknown because of the lack of long-term follow-up and study of the women. The 2006 Institute of Medicine Report, “Assessing the Medical Risks of Human Oocyte Donation for Stem Cell Research” states just how little is known about these women in the long-term because there is no monitoring and tracking.

The health risks of egg donation are serious and not fully understood. Because of the lack of follow-up and tracking of egg donors, those who do suffer complications are not reported in the medical literature; therefore the risks are underestimated. This lack of academic study and peer-reviewed publications on the aftermath for these women clearly makes informed consent impossible. Coupled with the payment-for-eggs plan, informed consent is even more coercive. Women who have financial need, even if told the risks, will assume that risk because of their financial need. Until we have done the necessary research to understand the short- and long-term risks to healthy young women, it would be a breach of our fiduciary responsibilities to ask them to enter into such an experimental scientific endeavor. Unlike a research subject in a clinical trial, with built-in protections and safeguards, the egg donor is seen as a commodity, a mere provider of a necessary resource. The conflicts of interest among the researchers who spur this high demand for eggs should be a red flag.

The goal of eliminating mitochondrial disease is praiseworthy. Yet advances in science should not come at the expense of our core humanity. To allow this procedure would do far more damage to that humanity in the long run, as it would be a major step toward the engineering and commodification of human life.

Jennifer Lahl is President of the Center for Bioethics and Culture Network;

Gene Tarne is Senior Analyst for the Charlotte Lozier Institute.